"Whitest paint on record" reflects 98 per cent of sunlight to cool buildings

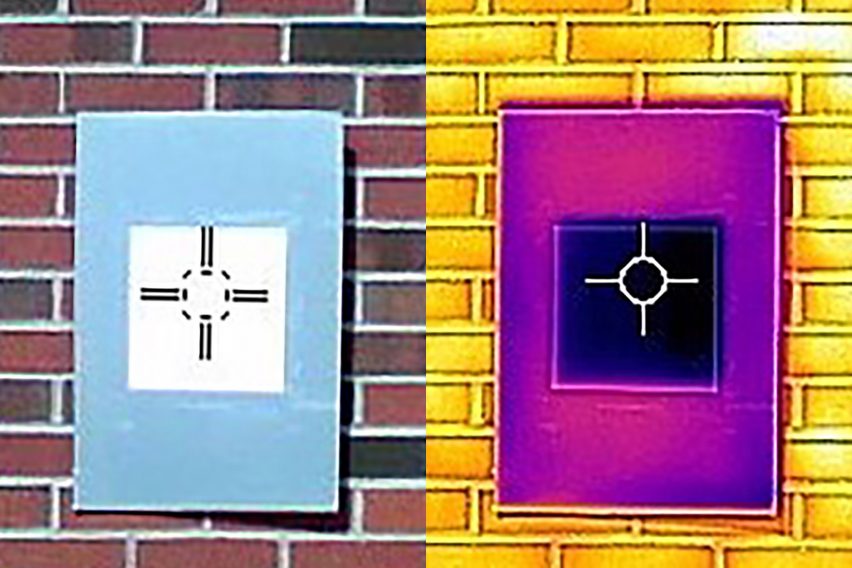

Researchers at Purdue University have developed an "ultra-white" paint that reflects 98 per cent of sunlight and deflects infrared heat, allowing buildings to cool below the surrounding air temperature.

The paint, which the university describes as the "whitest paint on record", owes its cooling power to barium sulphate – a pigment derived from the mineral barite – and reflects up to 98.1% of sunlight.

Unlike the titanium dioxide used in traditional white paints, which absorbs UV light, the barium sulphate is also capable of deflecting infrared heat away from the surface to which it is applied.

The researchers used barium sulphate in a high concentration of 60 per cent and in pigment particles of various sizes, which allows the paint to scatter more of the light spectrum from the sun.

"A high concentration of particles that are also different sizes gives the paint the broadest spectral scattering, which contributes to the highest reflectance," explained Joseph Peoples, a Purdue University PhD student in mechanical engineering.

This is what allows the paint to cool a surface below its surrounding air temperature, unlike other reflective white paints on the market which generally reflect 80 to 90 per cent of sunlight while absorbing infrared heat.

A higher concentration of barium sulphate would likely cause the paint to break or peel off, according to the researchers.

Whitest white paint can reduce need for air-conditioning

When applied to the roof and walls of a building, the paint can reduce the need for air-conditioning and the associated carbon emissions.

Adopted at scale, the university researchers say the passive cooling technology could help to combat the urban island effect, which sees cities retain heat through their infrastructure, instead turning them into reflective islands – much like the polar ice caps – to help combat global warming.

Tests have shown that the paint is able to keep a given surface four degrees Celsius cooler than its ambient temperature in noon sunlight and up to 10 degrees Celsius colder at night.

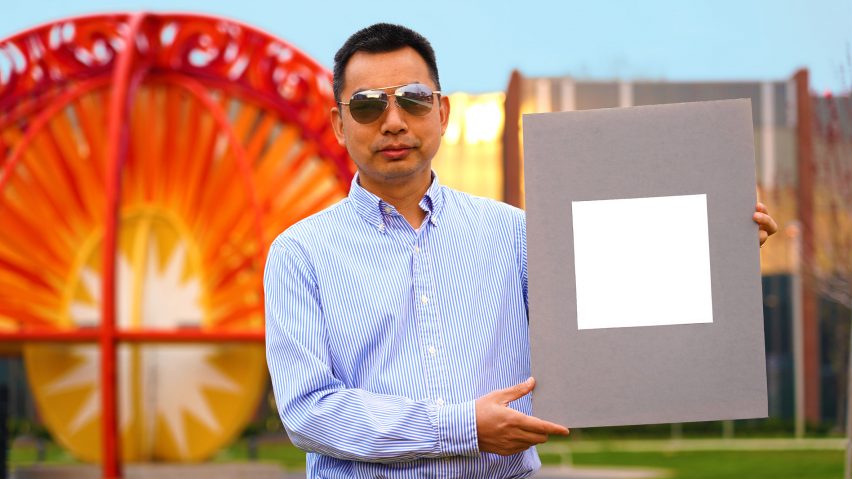

"If you were to use this paint to cover a roof area of about 1,000 square feet [93 square metres], we estimate that you could get a cooling power of 10 kilowatts," said Xiulin Ruan, a professor of mechanical engineering who led the research at Purdue University.

"That's more powerful than the central air conditioners used by most houses."

Paint is the "closest equivalent" to Vantablack

The paint is the result of a six-year research project, which saw Ruan's team assess more than 100 materials before testing 50 formulations for each of the 10 most promising.

Last October, the team unveiled another paint made from calcium carbonate that reflects 95.5 per cent of sunlight.

The researchers believe their latest patent-pending material is the "closest equivalent" to Vantablack – the blackest black developed by artist Anish Kapoor, which absorbs 99.9 per cent of visible light.

According to a study published in the ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces journal, the paint can withstand outdoor conditions and could be fabricated using the same processes used in commercial paint production.

The "ultra-white" paint could be on the market in one to two years for a comparable price to conventional paint, Purdue University told the Guardian.

Other reflective paints, such as The Coolest White developed by UNStudio and Monopol Colors, often have to be applied to or incorporate a reflective metal layer, which can limit their applications.

White roofing could offset carbon emissions

Previously, a 2017 project in Ahmedabad, India saw 3,000 city rooftops painted with white lime and a reflective coating, while volunteers in New York took it upon themselves to whitewash about 650,000 square metres of tar rooftops.

Studies have shown that the practice could help lower maximum temperatures in cities during a heatwave by two degrees Celsius or more, while researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory estimate that implementing reflective roofing and pavements worldwide could produce a cooling effect equivalent to taking 300 million cars off the road for 20 years.

However, other studies have warned that the practise could lead to unintended side-effects, such as reducing rainfall in cities located in drier climates.