Seven key materials designers are relying on to create more sustainable products

To mark Earth Day, we've rounded up seven materials that designers are using to replace more polluting mainstays such as plastic, concrete and leather in a bid to limit the impacts of climate change.

With a recent study finding that human-made materials now outweigh the total mass of Earth's living biomass, designers are becoming increasingly aware of how the products they design impact the planet.

From using renewable, carbon capturing materials such as cork, algae and latex to turning reclaimed food waste into food packaging, the focus is now on the entire lifecycle of a product. This includes how raw ingredients are sourced and how they can ultimately be reused, recycled or returned to nature once the product reaches the end of its life.

Read on for the seven key materials designers are reaching for to mitigate the environmental impact of their work:

Mycelium leather

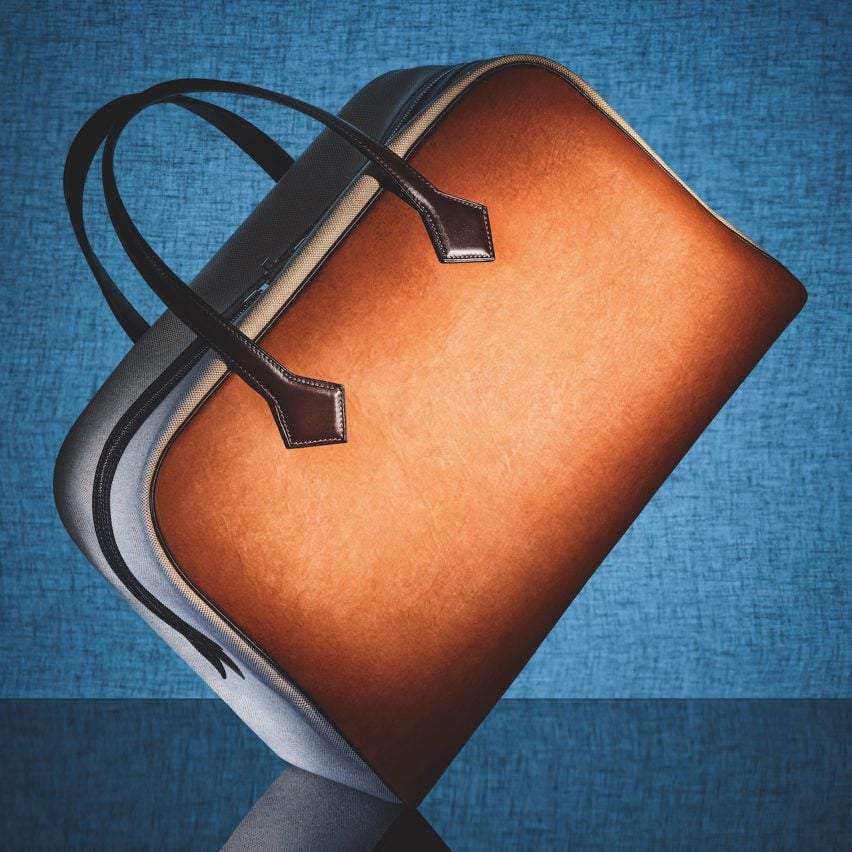

As the fashion industry looks to replace animal leather and its synthetic substitutes, a number of high-profile brands have hedged their bets on alternatives made from mycelium – the root-like structure that fungi use to grow.

The leather is grown from spores in a lab, which expands into a sheet of interwoven filaments that is then tanned and dyed to recreate the look and feel of real leather.

Biomaterial companies claim that mycelium leather emits fewer greenhouse gases and consumes fewer natural resources in its production than the manufacture of plastic leather and the rearing of livestock, which is responsible for 14 per cent of all greenhouse emissions from human activity.

In the past two months alone, Hermès has unveiled a bag (above) made from the material, British designer Stella McCartney has used it to create a two-piece outfit and Adidas has revealed a mycelium version of its Stan Smith trainers, as companies are rushing to scale up the material for mass-production and make it commercially available.

Latex

Latex is a natural material, which is derived from the titular, milky white sap of the rubber tree in a process called tapping. This involves scoring its bark rather than felling the whole tree, meaning the material is rapidly renewable.

Thanks to its environmental credentials, designers are increasingly using the material as a sustainable alternative to animal- and petroleum-based materials.

Fashion designers such as Harikrishnan and Fredrik Tjærandsen used the material instead of synthetic rubber or polyvinyl chloride (PVC), while Australian designer Molly Younger substituted leather for latex to create a series of flesh-like bags.

In the furniture industry, designers are combining it with natural aggregates to replace upholstery foam, which is made from polyurethane plastic and cannot be recycled. Designer Nina Edwards Anker mixed latex with lentil beans to pad out her Beanie Sofa while Richard Hutten used latex and coconut fibre to finish his Blink seating system for Amsterdam's Schiphol airport (above).

Concrete substitutes

Concrete is the most widely used construction material in the world and its production is singularly responsible for eight per cent of global CO2 emissions every year.

In a bid to mitigate this, material researchers have developed a range of different alternatives. One of these, called Finite, is made from desert sand instead of special construction-grade sand and its inventors' claim has "less than half the CO2 footprint" of concrete.

Elsewhere, London studio Newtab-22 has created its concrete-like Sea Stone using a natural binder and waste seashells from the seafood industry, which are rich in calcium carbonate – a compound that is also used to make concrete's key ingredient cement.

Central Saint Martins graduates Brigitte Kock and Irene Roca Moracia took a different approach and created "bio-concrete" tiles from invasive species (above) to encourage their removal and help to regenerate local biodiversity.

Algae bioplastic

Bioplastic has long been heralded as a possible solution to the plastic crisis. But environmentalists have raised concerns that mass adoption of polylactic acid (PLA) – the most common type of bioplastic, which is made from corn, sugar cane and other plants – would require vast amounts of farmland to produce. This would cause environmental damage and divert crucial food supplies away from the earth's growing population.

As an alternative, designers have started experimenting with bioplastic made from marine algae, an abundant and renewable natural resource that captures carbon from the atmosphere throughout its life.

"Three-quarters of the surface of the earth is ocean," designer Charlotte McCurdy told Dezeen. "If we want to break our dependence on fossilised carbon, carbon sequestered by algae and turned into durable materials represents an opportunity we cannot ignore."

McCurdy has created sequins (above) and an entire raincoat from algae bioplastic, while others have formed the material into skis, food packaging and filaments for 3D printing.

Food waste

Repurposing waste streams is a crucial step in moving towards a circular economy, where materials are constantly reused and no elements are wasted. A number of designers have turned to byproducts of the food and drinks industry in particular as these offer a treasure trove of natural materials.

Among the most useful ingredient are discarded seafood shells, which contain a biopolymer called chitin that designers have used to create bioplastic packaging and combined with waste coffee grounds to create a leather alternative.

Others have repurposed slaughterhouse waste such as animal blood, skin and bones to create a range of homeware and food packaging (above) as well as a bio-leather trainer.

Similarly, fruit and vegetable leftovers have been turned into bioplastic cups, packaging and leather alternatives such as Piñatex, while Filipino engineer Carvey Ehren Maigue has turned the food waste into solar panels that can generate clean energy from ultraviolet light.

Cork

Cork, which is derived from the outer bark of the cork oak, is becoming increasingly popular among designers because it is compostable, recyclable and can be stripped from the tree without cutting it down, allowing the plant to continue capturing carbon.

For every ton of cork produced, cork oak forests capture an estimated 73 tons of CO2, making the material effectively carbon negative.

Beyond being used as cladding in architecture, Jasper Morrison has turned offcuts from wine cork production into a series of furniture while Tom Dixon charred the material to create his "sound absorbent, fireproof, water-resistant" Cork collection (above).

Portuguese studio Digitalab has also spun the material into threads and woven them together to form a collection of lighting and homeware.

Bacterial nanocellulose

Another leather alternative is bacterial nanocellulose (BNC), which is produced by a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast, also known as SCOBY and used to create the fermented tea drink kombucha.

The material is subjected to a tanning and dyeing process to create a bio-leather that material scientist Theanne Schiros claims has up to a 97 per cent lower carbon footprint than synthetic polyurethane (PU) leather and will degrade in a domestic compost heap in a matter of months.

Schiros has previously used the material to create a pair of trainers in collaboration with New York streetwear label Public School (above), while Studio Lionne van Deursen used BNC to create a leather-like shade for a series of lights.

Others including Central Saint Martins graduate Rosie Broadhead and teams from MIT Media Lab and the Royal College of Art have used live bacteria to create clothes that reduce body odour or peel back in reaction to sweat.