"The possibilities are infinite" when you bring theatre into virtual space, according to the designers behind pioneering nightclub experience Eschaton.

Combining elements of cabaret, immersive theatre and video games, Eschaton is a virtual experience that pushes video chat technology to new levels.

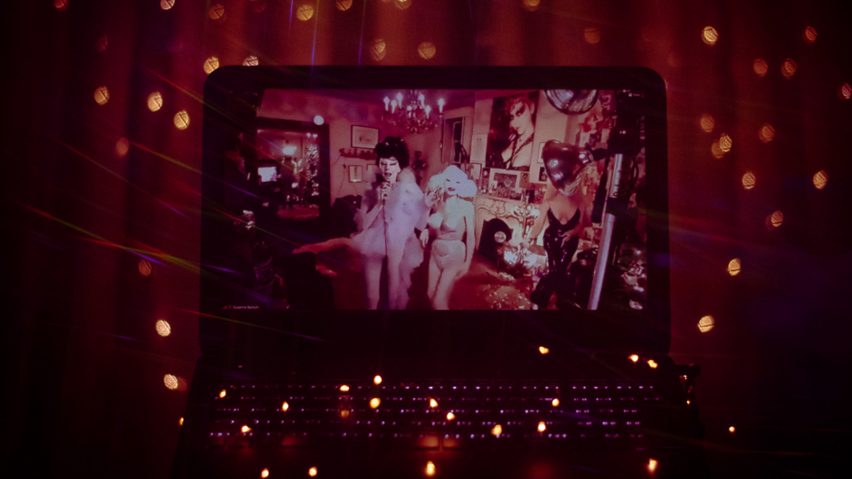

Visitors are invited to explore a seemingly endless number of rooms – each contained within a Zoom window – where they can encounter anything from a burlesque performance to a murder mystery.

These rooms are framed within a virtual world filled with mysterious portals and secret passwords.

For the show's producers, Brittany Blum and Tessa Whitehead of Chorus Productions, the online format allowed them to explore methods of staging that would have been completely impossible in a physical production.

"We could build an incredibly rich, complex and sprawling world," explained Whitehead, who is also the show's writer.

"Even though the dimensionality is flattened in one direction, because you're looking at a computer screen, we could really widen the net in another direction," she told Dezeen. "We could create this feeling of a rabbit hole where there's so much to explore."

"Virtually, there are no limitations"

Blum and Whitehead had originally planned Eschaton as an in-person experience, in the spirit of immersive theatre productions like Punchdrunk's Sleep No More.

They were already developing the concept when the Covid-19 pandemic forced New York into a state of lockdown in March 2020. Instead of delaying indefinitely, they decided their best option was to switch to virtual.

They assembled a creative team that included director Taylor Myers, interaction designer Jae Lee, branding designer David Good and web design studio BenBenBen, to explore how Eschaton could be better experienced through a screen rather than in person.

In this new format, they were no longer constrained in terms of scale; they could have as many rooms and characters as they wanted, without having to pay for the physical real estate, and they could fully exploit a trial-and-error approach.

"There's only so much time, money and labour you can spend building something physical before you need to make it work. But virtually, there are no limitations," said Whitehead.

"From early on in the process we had upwards of 24 to 26 rooms for every show."

A new type of world-building

Because of the digital format, Eschaton takes as much inspiration from video games as it does from theatre and film. By presenting visitors with virtual doors and transition spaces, the feeling of moving through a world is enhanced.

Lee said the aim was to "embrace the nebulous nature of the internet and translate that space into design".

"Early on we were looking at Zork and other early 16-bit video games," she said. "We borrowed from anything that felt like it truly had a moment in world-building, or that offered a great way to introduce a piece of lore to the audience without them having to solve a 15-minute puzzle."

Within this format of layering virtual elements over physical spaces, there is inherent flexibility. Lee can add in new graphic elements, and then just as easily remove them again the following week.

"The possibilities are infinite when it comes to things that you can do online," she said. "That medium, as it translates to the audience, is something that we can control almost holistically."

Like Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory

Narrative is key to the staging of Eschaton. To prevent the experience feeling like a series of disparate Zoom windows, every character and environment is created with a relationship to a mysterious central figure known as Mary.

The rooms contain puzzles, allowing the audience to follow this mystery though different spaces. However it's not essential to solve these puzzles every time.

Whitehead describes the experience as being like a visit to Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory. You can either explore the place on your own terms, or you can follow a narrative journey set out for you, just like you do in the story of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

"Eschaton is more akin to the Chocolate Factory," she said. "It is a place full of dark mysteries and wonders, and there's something new and weird to see behind every single door."

"However once you open one of those doors, if you're interested in following this mystery of Mary, then you can branch off into the serialised drama."

Combining virtual and physical experiences

Eschaton first launched in May 2020 and has built up a large audience of regular visitors over the past year.

Whitehead believes this audience will endure, even after physical theatre and nightlife venues are able to open as normal again.

So instead of converting Eschaton back into a physical event, the future ambition is to find more creative ways to overlay physical and virtual environments.

For instance, she suggests that a visitor might be given a virtual token in Eschaton, then receive a physical version of that token in the mail the next day. It might contain details of a venue where the person can have a one-on-one interaction with a character.

"We can find this more interesting, complex and nuanced balance between virtual life and in-person life, because we don't want to give up on either," Whitehead said.

"We don't want to separate the virtual Eschaton from the pop-up activation of Eschaton. The two can live together, support each other and bring out shades and colours of one another."

Virtual design has become more prominent as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, with designers increasingly working in the metaverse and exhibitions taking place in virtual spaces.

Read on for the full interview with Whitehead and Lee:

Amy Frearson: How did the staging concept for Eschaton develop?

Tessa Whitehead: Brittany Blum created Chorus Productions almost two years ago – she's the CEO – and after a month she brought me in as artistic director. When you're creating your first project together as two creatives, you look for common ground. We had both previously been performers and shared an almost obsessive nature about performing and all the rituals and superstitions surrounding it. It felt religious to us. So we started exploring this idea of live performance, particularly in a cabaret or a nightlife setting, and how it can be nearly mystical. We saw a commonality between mystery novels, shows and films, from David Lynch to Twin Peaks, and the nature of being a performer. We wanted to set some sort of mystery within a nightclub. That was our goal from day one.

We spent about nine months developing the show that would later become Eschaton. We had five scripts, we were looking at casting, and we were going on tours of amazing, old, decrepit buildings in Bushwick, Williamsburg and Sunset Park, and getting really inspired about bringing these scripts to life. Then the pandemic hit.

We spent about a week wondering whether the entire industry was going to collapse. Then we thought, we can either sit here and feel defeated for God knows how long, or we can see what we can put up online. We gave ourselves a deadline of two weeks. We called all the best people we knew, including Jae Lee, who we brought in as director of experience design, and workshop director Taylor Myers. We said no matter what happened, we were going to do something on that Saturday. And that is how we adapted Eschaton from being a physical in-person show to being virtual.

There were so many ramifications that we weren't expecting, which were terrifying but also exciting and inspiring. I knew nothing about tech and had never used Zoom. All we could do was describe the things in our heads, and Jae brought that to life in a virtual space. It was just unbelievable.

Amy Frearson: How did the concept change when you switched from physical to digital?

Jae Lee: The core ideals are still there. The core mechanics that we wanted to give to people in real life are translated as much as they could be into digital form. Some of them actually translated better in the digital format.

For example, when we were talking about the in-person experience, we were always thinking about how we could introduce escape-room elements or game mechanics to help facilitate storytelling and a sense of exploration. That was something that, in the real world, had a lot of physical constraints; it's a lot more planning and there's a lot more that can go wrong. But the possibilities are infinite when it comes to things that you can do online. That medium, as it translates to the audience, is something that we can control almost holistically.

We worked with a few different designers, like BenBenBen and David Good, to bring as much design as we could to the web page and the experiences that support it. We wanted to give a feeling of space, but not define it in its physical constraints. We're trying to embrace the nebulous nature of the internet and translate that space into design.

Our longtime attendees will tell you that, some weeks, they will notice that something's different, but can't quite put their finger on what it is. We're always working behind the scenes to make sure those transitions are seamless, so that the world-building is truly rich and easy to fall into.

Amy Frearson: Can you give some examples of things you have been able to do in the virtual world, but which would have been impossible in the physical world?

Tessa Whitehead: I think we took the idea of trial and error to the next level. In terms of production, there's only so much time, money and labour you can spend building something physical before you need to make it work. But virtually, there are no limitations.

We can have one show where Jae designs a ton of graphic design in the vein of Valentine's Day, for example, to see how it affects the tone, the mood and the narrative. Then we can just take it off next week. It's a little bit like decorations, but much more ingrained in the actual experience of the show itself. Because we don't have the cost of physical builds, there's much more freedom to just try things out and see how they go.

There's also the relationship between real estate and the number of cast members. In New York City, it's all about paying for an incredibly expensive but awesome piece of real estate, then mitigating those costs, usually with a smart business model that maximises the ratio between the number of cast members and the size of your audience. Suddenly we didn't have any real-estate concerns at all. We could have a sprawling space.

From early on in the process we had upwards of 24 to 26 rooms for every show. Each Zoom room was a discrete space with framing, production design, and a cast member with a character and a narrative. That was really freeing; we could build an incredibly rich, complex and sprawling world. Even though the dimensionality is flattened in one direction, because you're looking at a computer screen, we could really wide net in another direction. We could create this feeling of a rabbit hole where there's so much to explore. We use the word maze on our website and in our messaging, and we don't use it lightly. In Eschaton, there's so much to get lost in. That sense of endless real estate and endless number of cast members is something we could never have done if we were a physical production.

Amy Frearson: What challenges does this format present, compared with a physical event?

Jae Lee: We went from mostly servicing a local community in New York to servicing everyone globally. The first week we officially opened, we had people from Brazil, Japan and all around Europe. The biggest chunk of the audience is from the US, because of the time zones. But we had to find a balance; how do we stay true to ourselves, but also give the platform to as many people as possible?

To do that, we try to make sure that everything feels like it is speaking a universal language. Sometimes we want to concentrate on a specific theme, for example, on Valentine's Day we had a Dolly Parton Vegas theme. Obviously that is a deeply saturated culture in the US. But I think the core values of that theme still resonate, regardless of where you are from and where you live.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me more about the design for the individual rooms? Where are they in the real world?

Tessa Whitehead: The onus is on our amazing performers; they do everything. They are their own tech people, their own lighting people, they do all the production design in their own homes or studios.

In the fictional sense, where these spaces are and how we create them is largely inspired by the idea of collage. Eschaton is a love letter to all of the things that inspire Brittany, Jae and I. It's equal parts nightclub, show and game, and all three intermingle. We have really strong touchstones that we try to bring into every single room. One huge inspiration was Infinite Jest, which is where the name Eschaton comes from. We try to bring out the theme of addiction, this addiction to performing, in every single room.

Jae Lee: One of the best things about going from physical to digital is that you're no longer just comparing yourselves to escape rooms. Now you have this whole world of digital gaming to reference and there's so much history.

Early on we were looking at Zork and other early 16-bit video games, which definitely do not live in the 4K world at all. We borrowed from anything that felt like it truly had a moment in world-building, or that offered a great way to introduce a piece of lore to the audience without them having to solve a 15-minute puzzle.

There were definitely a lot of moments where we put something in and then realised it was either way too hard or way too easy, or that it didn't say enough. We would then tweak or change. I'm sure a lot of these Triple-A video games have to do that as well. That's inevitable when you're dealing with an audience of this size and diversity.

The world that we're creating is a lot more intermingled than I think a lot of people realise, because we want the audience to feel like they have been transported, and not just see one door, then another door, then another door. We really pushed that aspect. Tessa and I would talk about the narrative pieces she was developing, and how we could make some interactive experiences or add some puzzles in there. The same goes with the nightclub aspect. We had to balance the narrative so it would also work for people coming for a nightclub experience, who might not want to be pulled away to discover a murder mystery.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me about some of the narrative threads you created and how you wove those into the design?

Jae Lee: Our lady in red, so to speak, is this woman named Mary. She's an ambiguous figure that we've put a lot of attributes and metaphors behind. She's the linchpin for all of the puzzle tracks that you are led down. There are also branching narratives. The 50 or so characters that Tessa has created all have intermingling relationships, and all have different places that they occupy in Eschaton. This all somehow feeds into this mystery of Mary.

Tessa Whitehead: It's definitely a non-traditional narrative experience. You're not going to get a beginning, a middle and an end in a structured narrative sense. It's not scripted and that's part of the fun behind it.

We think about it as being like Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory. It's a crazy, cool, interesting place that everyone wants to go to. It's a little bit dark sometimes and has a lot of weird mysteries going on, but it is a wonder unto itself. Then you also have the story of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which is Charlie's story of how he gets the golden ticket, goes to the Chocolate Factory and ends up befriending Willy Wonka.

Eschaton, the experience that you come to on Saturday night, is more akin to the Chocolate Factory. It is a place full of dark mysteries and wonders, and there's something new and weird to see behind every single door. It has a distinct tone, a sense of place and a seedy underbelly, but there's no distinct story.

However, once you open one of those doors, if you're interested in following this mystery of Mary, then you can branch off into the serialised drama of this Charlie and the Chocolate Factory story. It has a more scripted narrative, with all of those story mechanics that we know and love.

Amy Frearson: In design terms, what are the biggest differences between staging Eschaton and staging immersive theatre?

Tessa Whitehead: The biggest difference has been how quickly the landscape is changing. Whenever I've done any sort of in-person show experience, even if it's ongoing, there is a point that you get to where it's locked and things are generally the same. Even if the show evolves in certain ways, the building always looks the same. The people might change, but the elements don't change.

Right now we're in such a time of tumultuousness that everything is constantly shifting. The technology is developing so quickly that often it can feel like the foundations of the building you are performing in are shifting underneath you. It's a constant challenge to keep up with things. You have to remember your core ideals.

Amy Frearson: As we emerge from the pandemic, what does the future hold for Eschaton? Will the format change as physical experiences become possible again?

Tessa Whitehead: There has been undue burden on virtual life for the past year now. It saved our lives. If I was sick, and I couldn't get to go to the grocery store, I could order food delivered to my door, I could order toilet paper, anything. I could get all of my entertainment and escapism online. That made Eschaton what it is and I'm forever grateful for that.

What's coming next is that all the burden doesn't have to be on virtual anymore. We can find this more interesting, complex and nuanced balance between virtual life and in-person life, because we don't want to give up on either. We truly believe that both are important to all facets of life. What we're really excited about it is figuring out a healthy and safe way to bring Eschaton into real life, finding a way to interweave those two universes. We don't want to separate the virtual Eschaton from the pop-up activation of Eschaton. The two can live together, support each other and bring out shades and colours of one another.

Jae Lee: We unknowingly stumbled into a new era of digital entertainment. A lot of people, myself included, believe this form of entertainment was inevitable at some point in the near or far future. It was just accelerated by the pandemic. I think it's now here to stay, until the internet dies or computers die. But it's up to us to define what that looks like.

It could mean that we are doing in-person pop-ups at the same time as doing digital. It could also mean we have a digital presence for certain seasons and physical presence for others. It's not to say that we're going to move to physical and then the rest is going to stay as it has always been. What we learn from one will always impact the other.

Tessa Whitehead: Finding unique ways to connect to unexpected experiences is what gets us excited. There may not be any actual connection between the two worlds. Say we're hosting a small run of a show in-person in, maybe in a cool speakeasy space in Nashville for three weeks. It could be connected to the virtual story via a narrative arc. You could be in Eschaton on a Saturday night and you have a one-on-one with a special character who shows you a token. The next day, you actually get that token in the mail. With it is a note that tells you take this token to an address at a certain time. You show up on a Tuesday and present your token and suddenly you're brought into a physical world where a performer is telling you a tragic tale of how she escaped Eschaton.

So there are ways of finding connections, beyond just having things happen simultaneously or live-streaming parts of a physical production.

Amy Frearson: How much more scope is there to build a community in Eschaton, as opposed to a nightclub or theatre?

Jae Lee: That's the best gift that we have received through Eschaton. We put it out there as a piece of art and what we got in return was an audience that is incredibly loyal, passionate and creative in their own right.

There are special moments that we all see. On Halloween, we crafted this really communal ending where everyone was together in one room. It was a very sweet, melancholy moment of everyone coming together. People were saying, this is beautiful, I feel so at home here. You could see people crying and laughing, enjoying this shared moment. Even though there were 400 people in that room, it felt oddly very intimate. And I remember walking away from that show shaking. It felt so incredibly powerful. I hope we never lose that.