Little Island designed to create "the feeling of leaving Manhattan behind" says Thomas Heatherwick

The elevated topography of Little Island was designed to create a sense of escape from Manhattan, according to designer Thomas Heatherwick in this interview with Dezeen.

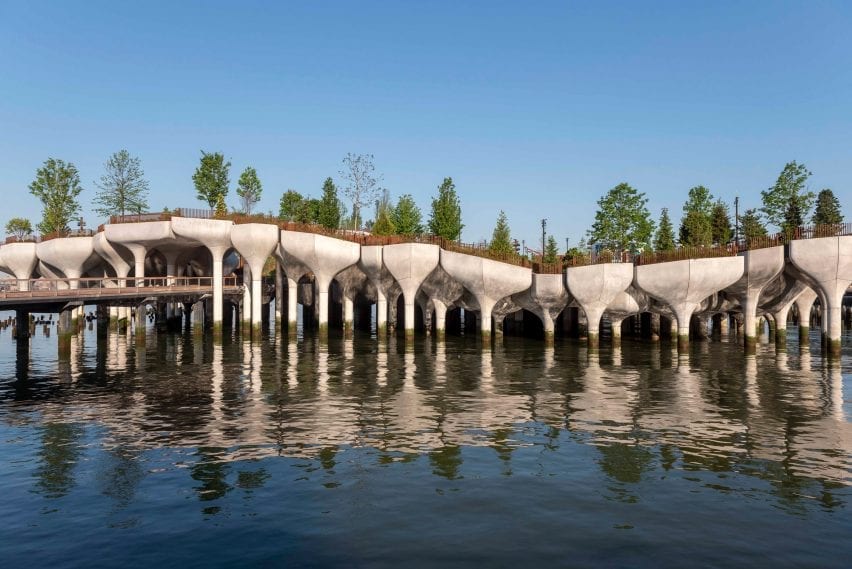

Designed in partnership with global engineering firm Arup and landscape architects MNLA, Little Island rests on 132 concrete columns over the Hudson River near New York City's Meatpacking District. It opened to the public last week.

Heatherwick was originally asked to design a pavilion for a traditional flat pier, but his studio pitched the idea for an undulating island away from the mainland.

By building a park out over the Hudson, accessible only by gangplank-style bridges, Heatherwick hopes visitors can experience "the feeling of actually leaving Manhattan behind".

"[It's] somewhere that would give a sort of emotional permission to look back at New York from somewhere other than New York," he told Dezeen.

Originally called Pier 55, the park sits near the remains of Pier 54. The historic structure, where survivors of the Titanic disembarked in 1912, is now reduced to clusters of wooden piles sticking out of the water.

Little Island's design was informed by "ghost piers" such as this, according to Heatherwick.

"Normally there's a lid put over them," he said. "The reason that the old piers are interesting is that they've had the lid lifted away and that exposes these piles."

Little Island's forest of concrete columns pays homage to these structures by making a feature out of its undergirding, Heatherwick said.

"We let the piles that we need to have become the containers for the earth and plant material," he explained. "It was our version of minimalism, to not add another ingredient, we just focus on that one ingredient."

Little Island design altered after Hurricane Sandy

According to Heatherwick, Little Island was originally going to be built closer to the water.

However, the design was altered after Heatherwick and his team presented early designs for the structure on the day in 2012 that Hurricane Sandy hit New York, engulfing parts of the city in a deadly storm surge.

"As we walked out for the presentation, the wind was growing, the rain was increasing," Heatherwick recalled. "That night, the flooding really kicked in and did further damage to Pier 54, which was where it was originally planned for the project to go."

"It gave an extra mandate to strengthen any new structure being built extremely sturdily and lifting it that bit further from the water level to ensure that its chances of being flooded are hugely reduced," he added.

Little Island was raised around 13 feet (four metres) further above the waterline in response, Heatherwick estimates. The design team embraced this change, he said, exaggerating the elevation to capitalise on the sense of separation from the mainland.

"Who wants to be on a bigger bit of Manhattan when you can go to another place instead?" he asked.

"By lifting the piles up to create a three-dimensional topography, we can create very different kinds of planting landscape. You get more like an Alpine escarpment at the highest part, where the wind is the greatest, but then you get protected areas and different areas of shading."

Safety considerations necessitated the of use concrete for the main structure, according to Heatherwick, who said that the Hudson River Trust stipulated it for both the safety of the users and the marine environment.

"The forces of the Hudson River are massive on it," he explained. "The [existing] wooden ones are absolutely gorgeous. But they're not an option."

Each of the concrete piles is sunk deep into the riverbed. The six-metre wide planters at the top of each pile are formed from precast concrete sections that were fabricated offsite and transported by barge to the site. Each one is filled with soil to hold the hundreds of species of plants and trees that form the park.

The concrete piles are all at different heights, exaggerating the visibility of the engineering that went into the structure and creating an undulating topography for the park.

"By making an effective bowl by lifting all those corners up, it's sort of acting like a social condenser," said Heatherwick, who explained that the idea came from his visits to hill towns in Italy, where promenading and people-watching are key social activities.

"People love to see and be seen," he said.

Little Island has been almost a decade in the making. At one point it was touch-and-go as to whether the project would ever get built.

Construction ground to a halt in 2017 when opponents obtained a court ruling against it. But city governor Andrew Cuomo personally intervened and the project went ahead under the new banner of Little Island.

"It got stuck in the politics of New York," says Heatherwick.

"The loss to the city would have been very large, I think, to not go ahead with something like that."

The $260 million project was largely privately funded by businessman Barry Diller, who has an estimated personal fortune of $3.7 billion, and his fashion designer wife through their Diller-Von Furstenburg Family Foundation.

The foundation will pay for the maintenance of the structure for the next 20 years.

Cities have "lost their nerve" to create new public space

Privately owned public spaces are controversial. But without them, Heatherwick argued, architects today have scant opportunity to design for the public realm.

"Cities themselves have lost the confidence to create projects," said the designer. "The governments and councils are not commissioning it. It's like they lost their confidence. They lost their nerve."

"So it is in the hands of private organisations to be making the public space that we use, which is a sort of funny upside-down way."

Little Island is the latest in a line of projects in the public realm that Heatherwick has designed for private clients, including the Vessel viewpoint in New York and London's Coal Drops Yard.

Such projects enable architects and designers to advocate for public amenities, Heatherwick argued.

"Otherwise we just make dead art galleries everywhere. How many art galleries can you have?" he asked.

"I mean, it would be easy for a studio like ours to do lots of rich people's private homes. And that's not interesting to me. So I'd much rather do objects in the public realm. And yes, it's contentious, when it's privately owned space."

Visitors have to book timed tickets to access Little Island, but they are free. And Heatherwick was keen to highlight that there will be affordable tickets to the plays and shows put on at the park's performance spaces.

"There is a deep commitment to not just letting it be Manhattan elites," he said. "The subsidised tickets are for people from Harlem and the Bronx and all the boroughs around."

Vessel, Heatherwick's 16-storey viewing platform in the middle of Hudson Yards, came under fire when it came to light that any photos taken at the site would be owned by the company that runs it. Architecture critic Alan G Brake dubbed it "urban costume jewellery" in "a billionaire's fantasy".

With Little Island's bumpy journey to completion, Heatherwick might well have been braced for more criticism. But so far, the designer said, Little Island has been "very, very, very positively received".

"Maybe the thing is I should never go to my own projects anymore," he joked, referring to the fact that he has not yet been able to see Little Island in person.

Due to the pandemic, Heatherwick has been unable to visit New York since January 2020, when the very first trees on the island park were being planted.

"I want to reserve judgement for myself until I can see it," he said. " I haven't been there in so long. It's tantalising."

Photography is by Timothy Schenck.