Polestar's aim to produce a climate-neutral car is a "moonshot goal" says sustainability head

Plans to produce the Polestar 0 electric car without creating any carbon emissions is a challenge comparable to putting a man on the moon, according to Fredrika Klarén, the brand's head of sustainability.

The carmaker is aiming to eradicate all CO2 emissions from the entire supply chain of the vehicle, which is due to launch in 2030.

"This is truly a moonshot goal," Klarén told Dezeen.

"Just like JFK, we don't know how to land on the moon but we know that we need to do it," she said, referring to US president Kennedy's 1961 speech that pledged to put a man on the moon within a decade.

"Building the roadmap as we go"

"We're putting the goal out there and then we're building the roadmap as we go along."

Polestar will take the next nine years, starting from when the project was first announced this April, to develop the Polestar 0 and its production process so that it generates zero carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions.

This forms part of Polestar's wider goal of reaching climate neutrality by 2040.

The electric carmaker, which was founded in 2017 by Volvo and Chinese car brand Geely, has committed to undertaking lifecycle assessments of all new vehicles starting with the Polestar 2 model launched in 2019.

"We will declare this for all of the coming models," Klarén said. "And when we get to Polestar 0, you will see clearly that it has zero carbon footprint."

The production of the electric Polestar 2, which sold just over 8,700 units in the last half of 2020, creates 26.2 tonnes of CO2 emissions while a comparable petrol car generates only 16.1 tonnes, the brand claims. The next step is to get this down to zero for the Polestar 0.

Electric battery responsible for most emissions

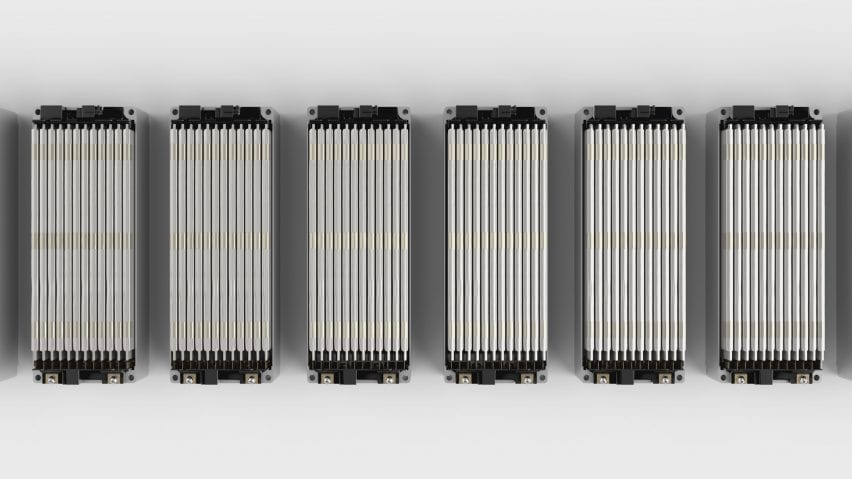

Higher emissions in EV production are largely due to the manufacturing of the sturdy steel-and-aluminium platform that houses the heavy battery as well as the lithium-ion battery itself, which contains metals such as cobalt and nickel that have to be mined and refined.

"With the Polestar 2, it's the battery and the big chunks of aluminium and steel that stand for maybe 70 per cent of the CO2 footprint," Klarén said.

"It is the raw material extraction and the processing of these three areas that are really the biggest culprits."

"We also have direct emissions stemming from aluminium production, for example, that will have to be eliminated or captured either through carbon capture or changing processes somehow," she added.

The lifetime emissions of an electric vehicle are highly dependant on the energy mix of the area where it is being charged and how much of it comes from renewable sources.

Hence the Polestar 0 project focuses only on eliminating emissions generated from cradle to gate – meaning from the sourcing of the raw materials to the time the finished car leaves the factory.

Recycling metal from scrapped cars

Polestar 2's life-cycle assessment, which is published online, is being used by the company's R&D department as a baseline for the Polestar 0 model to help them tackle the most carbon-intensive stages of creating a car.

As well as transitioning its entire supply chain to renewable energy, Polestar will minimise the number and quantity of raw materials used in the Polestar 0, Klarén said.

The team is also looking into reusing materials such as aluminium from scrapped cars.

"If you look at a car, you have a very high recyclability but somehow we are not completing the loop," Klarén explained.

"We don't have a large recycled content today in cars so that would be a challenge going forward."

Polestar is partnering with UK blockchain company Circulor to audit the emissions generated by the supply chains of metal components.

Circulor's technology works by creating a digital representation of the material in question, known as a digital twin, which serves as the material’s real-time counterpart so it can be traced on its journey from mine to factory.

Every transport or refinement step along the way is recorded on the blockchain. Here, the information cannot be altered or tampered with, so it can be used to hold suppliers accountable.

"We are setting hard targets for climate emission reductions and use of renewable energy," Klarén said. "The same goes for recycled content."

Using recyclable over bio-based materials

While the R&D department is investigating new materials and processes, Polestar's design team is looking at ways of decarbonising the surface materials and finishes that will be used in the Polestar 0.

"In terms of impact, these things are not as big as the mining and refining," said the company's head of design Maximilian Missoni.

"But if you want to really get to zero, at the last stage they become extremely crucial."

Here, the team is prioritising materials with a high degree of recyclability such as Econyl, a kind of regenerated nylon made from plastic waste that generates 50 per cent less emissions in its production than virgin nylon.

The company is also investigating the possibilities of flax-fibre composite panels created by Swiss company Bcomp, which Missoni says can rival the strength and lightness of carbon fibre but is recyclable.

"Everything generates emissions; even natural fibres," Missoni said.

"Sometimes you think if you use natural materials it must be better. But what we've learned is that if you use materials that are recycled and can be recycled, that can be a better solution from an emission point of view than if you use natural materials."

Unavoidable emissions will be offset

Polestar aims to cut out emissions from the production of the Polestar 0 entirely but says it will use offsets as a fallback to cover any potential gaps that might remain.

Klarén hopes that over the next nine years, direct air capture (DAC) technologies such as those pioneered by Climeworks will be scaled up and made more affordable, which would allow Polestar to pay to have unavoidable emissions removed from the atmosphere.

But the company will only use permanent, reliable offsetting methods rather than afforestation, which it regards as a less secure form of sequestration.

"When we are in 2030, hopefully, there will be direct capture methodologies to capture CO2 that might remain from some processes but we will not offset something that has too weak a link," Klarén said.

"So hopefully we will see capture technologies being developed and implemented because I think that they would be needed. But we will aim for zero regardless."

Carbon revolution

This article is part of Dezeen's carbon revolution series, which explores how this miracle material could be removed from the atmosphere and put to use on earth. Read all the content at: www.dezeen.com/carbon.

The sky photograph used in the carbon revolution graphic is by Taylor van Riper via Unsplash.