A return to traditional materials and construction techniques could help eliminate carbon emissions, says Pakistani architect Yasmeen Lari, who has built more than 45,000 homes from mud, lime and bamboo.

Designed for victims of natural disasters in Pakistan, the homes, built since 2005, form "the world's largest zero-carbon shelter programme," according to the RIBA.

"You're building something that's really affordable but at the same time there are no carbon emissions," Lari told Dezeen.

"There are lots of ancient wisdoms and techniques that have been used over the years but I can't imagine most so-called starchitects would even look at them."

"We have to rethink everything"

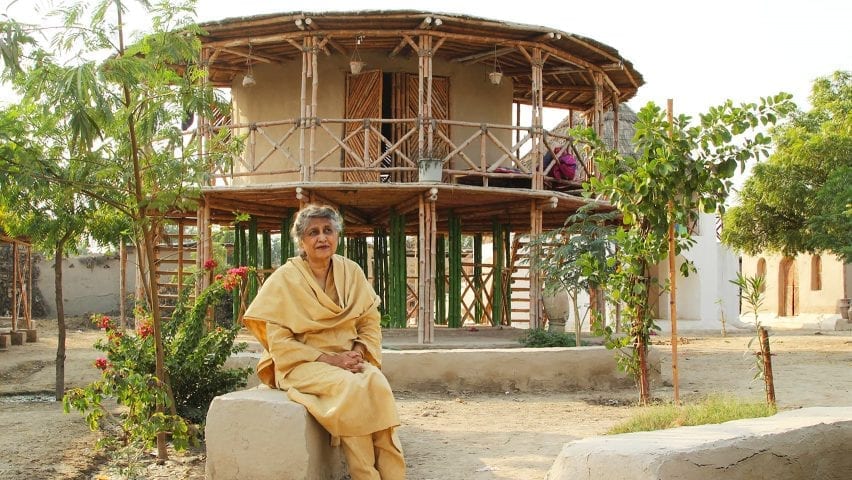

Lari, who became the first woman to qualify as an architect in Pakistan in 1963, was responsible for designing some of the country's landmark commercial buildings such as the Finance and Trade Centre and the Pakistan State Oil House.

But since she retired and closed her practice in 2000, Lari has been advocating for a different kind of "barefoot social architecture", which uplifts impoverished communities while treading lightly on the planet.

This involves substituting expensive, emissions-intensive materials such as concrete and steel, which need to be transported to site, with local ingredients that are low-carbon, low-cost and have been used in vernacular constructions for thousands of years.

"When you feel that you're a starchitect who knows everything, then you are not looking at the past at all," said Lari, who last year won the Jane Drew Prize for raising the profile of women in architecture.

"Most of the time, you're looking at the future and the future has always been very shiny," Lari added. "I built these buildings in the 1980s, which were shiny, lots of cement, lots of steel, reflective glass and all the rest of it."

"But that was a different time and a different world altogether. With climate change, with global warming, with Covid-19, we have to rethink everything and we must do it now."

"Every family in Pakistan" could build a shelter

Lari studied architecture at Oxford Brookes University before returning to her home country of Pakistan, where she has lived ever since.

She began her work in disaster risk reduction (DRR) in 2005, when one of the most destructive earthquakes of modern times ravaged the region of Kashmir, killing more than 80,000 people and leaving 3.5 million homeless.

In the absence of sufficient aid money, Lari developed a blueprint for a shelter that could be built by anyone using traditional mud construction.

"There was donor fatigue and there was no other way to do it except to follow my technique," she recalled.

Since then, the 80-year-old has trained thousands of locals in how to erect these shelters through the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, which she co-founded with her husband, as well as via open-source YouTube tutorials.

"Every family in Pakistan can do it, even below the poverty line," she said. "And we have more than 50 per cent of our population living below the poverty line."

Over time, the huts were adapted to withstand different natural disasters. Some are raised on stilts to protect from flooding and most feature cross-braced bamboo frames, based on a traditional construction technique known as dhijji, which do not endanger life during earthquakes.

"We've had so many of these disasters, almost every year," Lari said. "I'm very conscious of climate change impacts because we are probably the fifth or seventh in line for disasters."

"But this has given me the opportunity to work with different materials, which are local and natural," she added.

"And it turns out that they're all pretty good from [a carbon] point of view."

"It can be reused 100 times"

This helps to create buildings that can withstand the effects of global warming without further contributing to it.

Even though Lari hasn't undertaken a full lifecycle assessment of the shelters, she believes they are at least carbon-neutral.

"I can't say that I've done any kind of evaluation but I do know that earth has no carbon emissions," she said. "It's locally sourced, it's biodegradable, it can be reused 100 times."

Lari's other material is lime, which was employed by the Romans as an ingredient in concrete and used to build monuments including the Pantheon in Rome.

Lime is produced by heating limestone, which is a type of calcium carbonate. This releases the carbon into the atmosphere and leaves behind calcium oxide.

This compound, also called quicklime, is then mixed with water. And as the mixture hardens, it reabsorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

The lime continues to recarbonate throughout its lifetime, slowing turning back into limestone and reducing its carbon impact.

"The more you use it, the more carbon is absorbed," Lari said.

The bamboo Lari uses to reinforce her buildings is a fast-growing renewable resource that sequesters CO2 throughout its life.

"I do use a little bit of steel like hinges and bolts and so on," Lari said. "But I am presuming that whatever little emissions there might are counteracted by these materials."

According to the architect, her design also helps to keep the operational carbon footprint of the building low, due to the natural insulation provided by the earth and the ventilation via the thatched roof.

"I understand that not everybody will use bamboo and lime and earth but everybody can make an effort to lower the carbon footprint in every kind of structure," Lari said.

"Why is it that instead of cement we're not using lime in buildings? There are lots of different permutations that are possible and we can use them. But the problem is that architects are not thinking in that way."

Carbon revolution

This article is part of Dezeen's carbon revolution series, which explores how this miracle material could be removed from the atmosphere and put to use on earth. Read all the content at: www.dezeen.com/carbon.

The sky photograph used in the carbon revolution graphic is by Taylor van Riper via Unsplash.