Drive to reduce embodied carbon in buildings makes biomaterials market a "really exciting space"

Concerns over carbon emissions caused by the construction process are fuelling a surge of interest in biobased materials according to Arup research and innovation leader Jan Wurm.

Demand for biomaterials such as mycelium, hemp, algae, bamboo and cork is growing, Wurm said, as architects search for materials that store atmospheric carbon rather than emitting it.

"It's a really exciting space," Wurm told Dezeen. There are a lot of startups and a lot of grants. There's a lot of things happening."

Demand is being fuelled by the realisation that around half of the total carbon emitted by a building is caused before it even opens. This is known as embodied carbon.

"The big driver is the focus on whole-life carbon," Wurm said. "The focus has shifted from making buildings energy-efficient to looking at carbon."

The built environment is responsible for an estimated 40 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions but construction's role has been overlooked until recently, Wurm said.

"For a long time, the construction industry was not a sector being addressed when we talked about climate change," he said, pointing out that November's COP26 climate conference will have a dedicated built-environment day for the first time.

In addition, the European Commission this week announced proposals that would limit emissions from buildings for the first time.

"So it's now part of the overall discussion on climate change," Wurm said.

Wurm leads the European research and innovation team at Arup, the global architecture and engineering group that is headquartered in London.

He has worked on pioneering biomaterial projects including a 2013 project that used algae to generate electricity and the 2014 Hy-Fi project at MoMA PS1 in New York, where he collaborated with Evocative Design to develop the mycelium bricks used to build a temporary tower designed by design studio The Living.

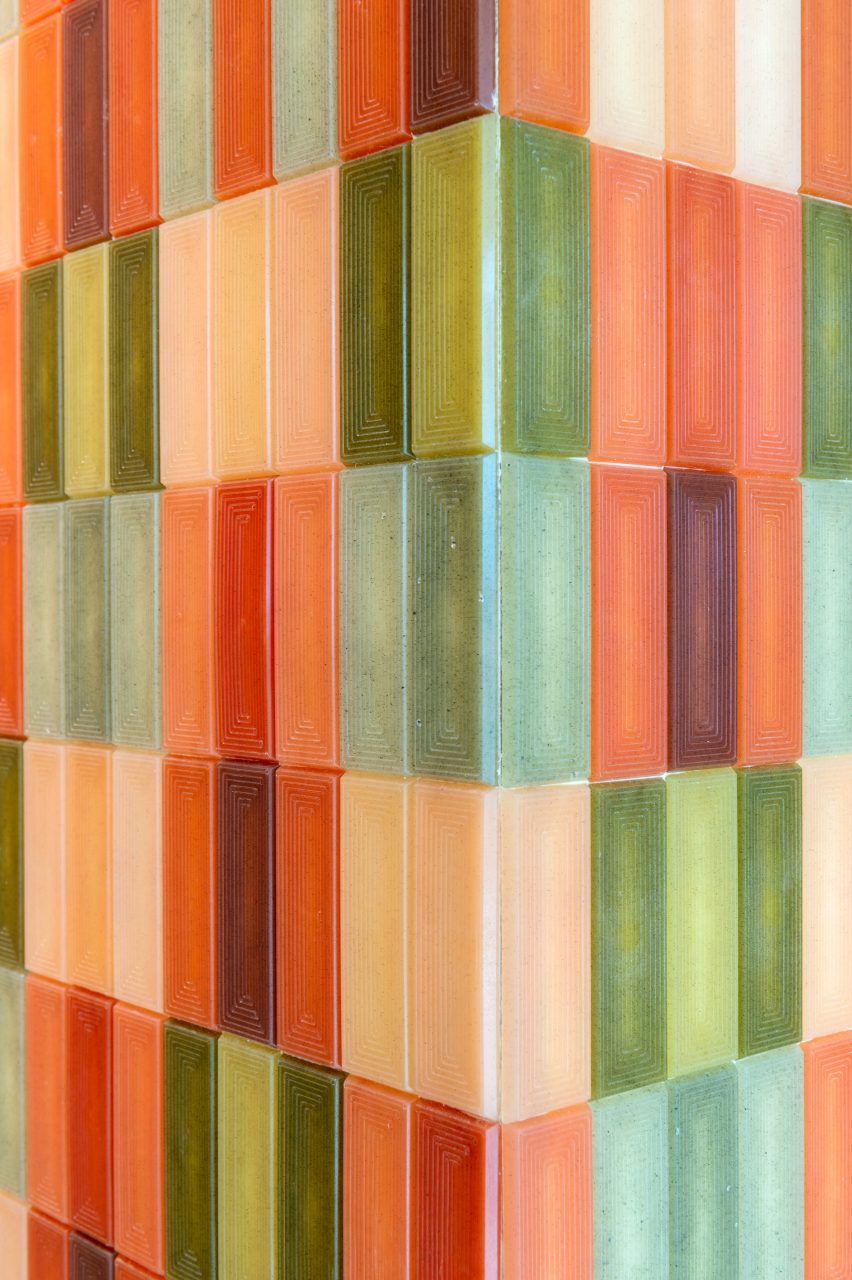

More recently, he has collaborated with Italian biodesign firm Mogu to create a range of acoustic wall panels made of mycelium, which is the underground part of fungus. It feeds on waste biomass such as sawdust, absorbing carbon as it grows. It is increasingly being used for packaging, insulation and products.

Mogu produces a variety of biobased materials including mycelium acoustic panels and flooring products from bioresins and agricultural waste. The new system developed with Arup, called Foresta, was unveiled this week.

The Foresta product joins a growing range of experimental biomaterials being used in construction projects. Materials research lab Atelier Luma has added interior finishes made of algae, sunflowers and salt to The Tower, a building by Frank Gehry at Luma Foundation in Arles, France.

Practice Architecture worked with hemp farmer Steve Barron to build Flat House, a home in Cambridgeshire, England, that features insulation and external cladding made of the cannabis variety.

Matthew Barnett Howland, Dido Milne and Oliver Wilton used cork blocks to build Cork House in Berkshire, England, which was shortlisted for the Stirling Prize.

Bioplastic brand Made of Air has clad a car dealership in Germany with panels made from farm waste mixed with bioresin.

Wurm said these experimental materials are now going mainstream and architects consider using them on major projects.

"Focus is shifting to embodied carbon," Wurm said. "Roughly over the whole life of a building, carbon emissions are 50 per cent embodied and 50 per cent operational."

"The big driver is the focus on whole-life carbon," Wurm said. "The focus has shifted from making buildings energy-efficient to looking at carbon."

The drive to create net-zero buildings that create no emissions over their entire lifecycle means that architects need to reduce embodied carbon, which includes all emissions generated by the manufacture of materials as well as the construction process itself.

Embodied carbon represents roughly half the carbon footprint of a building while operational carbon, which are emissions caused by the building in use, makes up the other half.

"If we want to bring emissions down to net-zero by 2050, that's where the big change has to happen," Wurm added, referring to the timeline of the 2015 Paris Agreement. This calls for all carbon emissions to end by 2050 to help meet the goal of keeping global warming within 1.5 degrees Celsius of pre-industrial levels.

Eliminating operational carbon is relatively straightforward, Wurm said. "There are solutions for energy. There are solutions for mobility. But how do we get the carbon footprint down for construction? That's a real issue to be addressed and that's why these biomass materials are really going up in demand."

It's much harder to tackle embodied carbon. Bringing these emissions down to zero is "impossible," according to Hélène Chartier, head of zero-carbon development at international network C40 Cities.

Chartier, who is coordinating C40 Cities' international competition to develop zero-carbon neighbourhoods, told Dezeen that architects should reduce embodied emissions as far as they can and then look for ways of offsetting the remainder.

"It's totally impossible," she told Dezeen in an interview. "So the question is really to push them to reduce embodied carbon to the maximum and then to offset the last part."

The more embodied emissions are reduced, the less leftover carbon there is that needs to be offset by other means such as making buildings carbon-negative during their use.

"The 50 per cent embodied carbon is released within a couple of years when the project's materials are fabricated and installed," Wurm said. "So there's a big release of carbon in a very short amount of time."

"And we don't basically then have enough time to make the savings through efficient operation of the building. It doesn't really help us to bring down the [lifetime] carbon footprint."

Biomaterials that sequester carbon via photosynthesis offer an obvious way of reducing the upfront carbon footprint of a building. Timber is the most popular biobased material but "timber takes 100 years to grow," Wurm said.

"So all the carbon we're storing has been built up over 100 years," when using timber, Wurm explained. "And we take down trees, which absorb quite a lot of carbon. Of course, we replant trees."

"But I think it's interesting to take the pressure away from forests and see what other materials we can use to capture carbon in a shorter time."

Recent timber shortages caused by increased demand and pandemic-related interruptions to supply chains have forced architects to seek natural alternatives, while new regulations in countries including France and the Netherlands is forcing them to turn to biomaterials.

"We're trying to find other bio-sourced materials and trying to find solutions to lower our carbon footprint by using mixed materials," French architect Lina Ghotmeh told Dezeen last month.

Biomaterials can be more effective at sequestering carbon than trees. Cambridge University materials researcher Darshil Shah told Dezeen that a field of fast-growing hemp absorbs twice as much carbon as an equivalent area of forest.

"This is why biomass materials are so interesting," said Wurm. "And especially fast-growing plants, because they absorb carbon quickly."

Carbon revolution

This article is part of Dezeen's carbon revolution series, which explores how this miracle material could be removed from the atmosphere and put to use on earth. Read all the content at: www.dezeen.com/carbon.

The sky photograph used in the carbon revolution graphic is by Taylor van Riper via Unsplash.