The shift to remote working from suburbs and the countryside due to the Covid-19 pandemic could lead to a huge rise in carbon emissions, according to Taylor Francis of decarbonisation platform Watershed.

The trend could increase migration from cities and lead to less sustainable lifestyles, he told Dezeen.

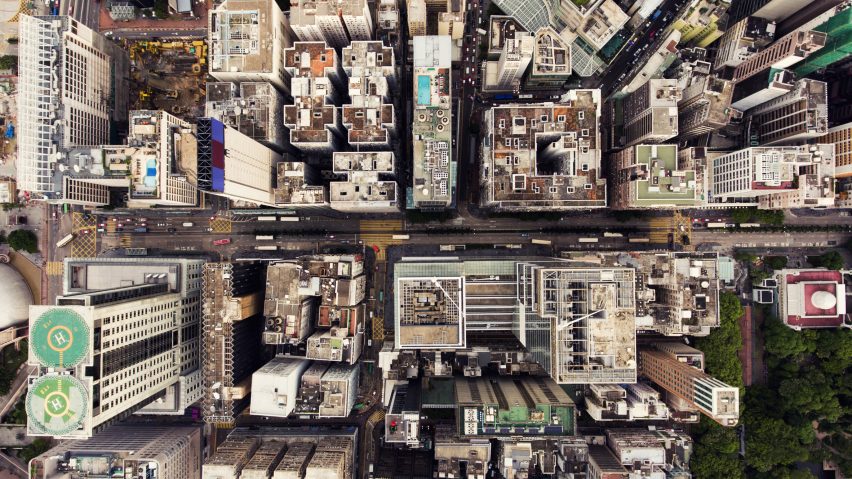

"One of the best tools we have in decarbonisation is urbanism," said Francis, who is co-founder of Watershed, which helps large companies eliminate their emissions.

"Everyone who lives in a city is way lower carbon than people who live in suburbs."

Remote working could be "quite negative" for climate change

Many companies claim their work-from-home policies have led to lower emissions but that is not necessarily the case, Francis said.

"One thing we're really concerned about is whether this kind of shift to remote work is actually incentivising people to move from San Francisco and London out into more suburban areas where they get a bigger home and buy an SUV," he continued.

"That's the way in which remote work could actually be quite negative from a climate impact perspective."

Remote working could also lead to more work-related travel if companies arrange regular offsite gatherings, he added, pointing to a free calculator on Watershed's website that helps calculate the climate impact of their remote-working policies.

"If we're all going to be doing this sort of thing over Zoom that used to require a flight to London, then the new world is good," he said.

"But if work from home means that people are going to travel more often for quarterly offsites, that actually means work from home is bad."

Watershed aims to "help companies get to zero carbon"

Watershed was founded in 2019 to help companies understand and eliminate their carbon emissions. Its clients include home-rental platform Airbnb, food delivery company DoorDash, restaurant chain Sweetgreen and fintech brands Revolut and Monzo.

It helped e-commerce platform Shopify develop its $5 million carbon-removal fund and worked with payments platform Stripe on its carbon removal project.

"Watershed is a software platform to help companies get to zero carbon," Francis said. "At a super high level, we think that every business in the world above a certain size over the next 10 years is going to have to integrate climate into how they run their company."

Francis said there is a surge of large companies taking climate seriously and scrambling to develop strategies to achieve net-zero emissions.

"There's a huge wave of companies at the board and exec level thinking about climate in a pretty serious way," he said, following pressure from legislation as well as investors such as BlackRock, the world's biggest financial asset manager, which has committed to make its investment portfolio net-zero by 2050.

"That pressure comes from public market investors like BlackRock and it comes from regulators," he added. "The UK is actually leading the way there. The US is a step or two behind it."

"True net-zero requires carbon removal"

Watershed takes its clients through a four-step process. First, it helps them measure their emissions by uploading data to an online dashboard. Next, it advises them on how to reduce emissions. Thirdly, it assists with atmospheric carbon removal, which involves helping companies "fund permanent, durable, high-impact carbon removal".

Finally, it facilitates reporting so investors, regulators, employees and supply chains can see how they're progressing.

Francis, along with other leading figures in the nascent carbontech industry, uses the phrase "carbon removal" instead of "offsetting" since the latter term is widely used to describe schemes that reduce emissions rather than negating them.

"We strongly believe that true net-zero requires carbon removal, which is taking carbon out of the atmosphere, rather than traditional offsets, which involve paying someone else not to emit carbon into the atmosphere," he said.

Tackling climate change "planet's number one objective"

Carbon removal involves actively removing carbon that has already entered the atmosphere via carbon capture techniques including soil sequestration, biomass and direct air capture.

"Every solution for us getting to zero carbon by 2050 includes five to 10 gigatonnes of durable carbon removal per year by the middle of the century," he explained.

"Right now we're in the thousands of tonnes, tens of thousands of tonnes of credible carbon removal when you strip away all the low-quality, low-impact carbon offsets. So that space needs to scale up enormously."

"I think it will," he added, given that tackling climate change has become "the planet's number one objective". "But that's the pinch point. Where are those five to 10 gigatonnes per year of carbon removal gonna come from?"

He urged companies to set up carbon removal portfolios to help fund the sector so it can develop more efficient sequestration methods and achieve scale. "Funding carbon removal to get around the pinch point is really important," he said.

"Your carbon footprint is primarily the carbon footprint of the companies you work with"

Companies are beginning to realise that their carbon footprints are inextricably entwined with those of their supply chains. This is leading them to demand transparency from suppliers so they can work with them to eliminate the tricky Scope 3 emissions.

These are emissions generated by a company's value chain but over which it does not have direct control. Companies need to eliminate these emissions – or negate them via carbon removal – in order to achieve net-zero.

"The big emerging center of gravity is around engagement between suppliers and their customers because your carbon footprint is primarily the carbon footprint of the companies you work with," he said.

"And that's true for most companies that are not heavy emitters themselves. That whole space is completely nascent. There needs to be a more interoperable standard for how companies share data about their carbon footprints and their carbon plans with their customers. That's part of the Watershed mission."

Overall, the built environment accounts for around 40 per cent of global emissions and the real-estate portfolios of large companies account for a huge proportion of their carbon footprints.

"The built environment is a very, very carbon-intensive space"

Reducing this has become a key focus for Watershed's clients. "When we do carbon footprint assessments for tech companies, their investment in new buildings, fit-outs and leasehold improvements ends up being near the top of the list almost all the time," Francis explained.

"The built environment is a very, very carbon-intensive space," he added, describing the situation as a "huge opportunity" for architects.

These companies "desperately want to fit out buildings in a low-carbon way or build new buildings in a low-carbon way," he added. "The thing that's exciting is that it's a dirty supply chain. But it's also a supply chain where there are low carbon options. There's a lot of possibilities out there."

However, companies tend to "get a blank response" from architects and construction firms.

"The common journey that I see is that customers who would be architects' clients say: 'Whoa, this is a wake-up call. We desperately want to fit out our building in a low-carbon way or build a new building in a low-carbon way'. And then they go to their contractors or architects and kind of get a blank response."

"So I think there's a huge opportunity for architecture firms, builders and contractors to have a low-carbon offering. Because companies are in the market for that."

Pressure building from investors and customers

Large architecture firms have been slow to join the net-zero movement. The profession is one of the least well-represented sectors in the UN's Race to Zero campaign while less than six per cent of UK practices have signed up to the RIBA's net-zero challenge.

Architects tend to respond by saying they can't force their clients to commission net-zero buildings, which are buildings that make no contribution to atmospheric carbon across their whole lifecycle including both construction and use.

Does Francis buy that argument? "No I don't," he replied.

Watershed is not yet working with any of the heavy-emitting companies such as oil-and-gas firms or cement manufacturers. But he believes that pressure from investors, legislators and customers will force them to clean up their acts.

"Our strategy is to work with companies that are at least one step downstream of the heavy emitters," he said. "Because I think there's this really interesting pressure that is building from investors and customers to companies."

"It ends up manifesting in demand for low-carbon solutions from the commodity providers. And so that's where we really spend our time."

Carbon revolution

This article is part of Dezeen's carbon revolution series, which explores how this miracle material could be removed from the atmosphere and put to use on earth. Read all the content at: www.dezeen.com/carbon.

The sky photograph used in the carbon revolution graphic is by Taylor van Riper via Unsplash.