Looop Can is a sanitary pad washing device for refugees

Product design student Cheuk Laam Wong has created Looop Can, a concept for a portable kit to clean menstruation pads that aims to reduce period poverty among refugees.

Each Looop Can kit includes a container for cleaning, 70 grams of baking soda and a reusable sanitary pad made from bamboo terry fabric called the Looop Pad.

Made from a recycled steel can, the washing device can be used to clean sanitary pads with just baking soda and 500 millilitres of water.

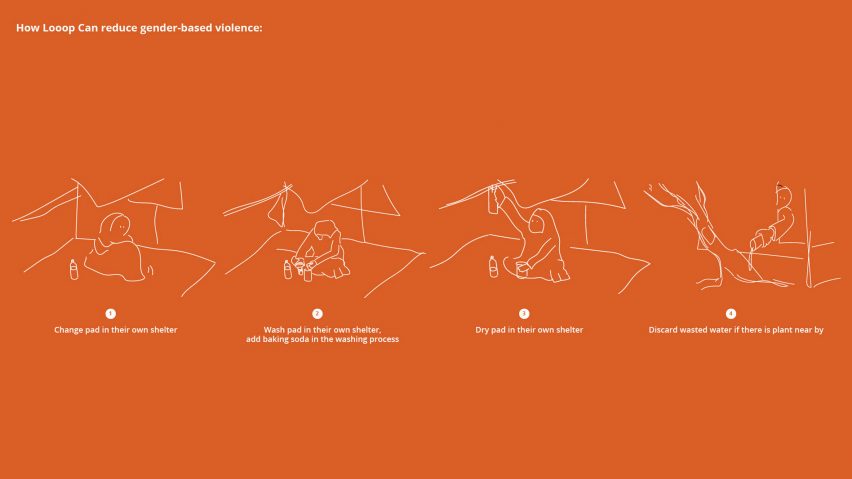

The kit has been designed so that women living in refugee camps can easily and discretely wash and dry their sanitary pads.

"Almost 60 per cent of female refugees suffer period-poverty problems as they spend their limited funds on food or nappies for their babies," Cheuk told Dezeen.

"A washing kit for reusable sanitary pads will benefit not only refugees and asylum seekers, but also people who have limited finances and insufficient education about menstrual health management," she continued.

The Looop Can comprises a main cylindrical body with a screw-top lid and a hollow spinning device that can also be used to store the baking soda.

When the sanitary pad requires cleaning, the user places the pad inside the can before immersing it in water and baking soda, a natural cleaning detergent that helps to remove blood stains.

Once the cap has been screwed on, users can spin the device with their finger which requires "minimal human effort so that people who have period cramps can wash easily," the designer explained.

The spinning motion helps the baking soda and water to clean the pad. The user must then wait at least 30 minutes until the blood dissolves, before rinsing the pad three times.

After interviewing NGOs in Greece refugee camps, Cheuk realised that there was a need for a cheaper, longer-term solution to plastic pads.

"Plastic pads can’t work as they rely on NGOs' constant donation and lack culturally sensitive disposable methods," the designer said.

Although reusable pads are a slightly better alternative, Cheuk found that shared washing machines in refugee camps aren't always available for everyone.

"It means that people need to dry the laundry in their shelter and everyone can see," she explained.

By contrast, the reusable Looop Pads can be hung up to dry indoors and, if cared for properly, can last for up to five years.

According to Cheuk, "this covers the minimum time a refugee is likely to stay in a camp waiting for identity approval".

Each Looop Pad comes in three modular parts: a base made from bamboo terry, a bamboo fleece wing and the pad itself. This is made from a polyester-laminated material – a waterproof fabric used in nappies, diaper bags and mattress covers.

"Through researching the material used in reusable pads, I designed the pad to have separable layers so that they dry quicker regardless of the weather. The quick-drying bamboo fabric became an ideal option," the student explained.

The pads are cut into a rectangular shape so that they don't resemble sanitary pads, something that can help minimise embarrassment and stigma associated with menstrual products.

"When the pad is hung up to dry, it isn’t obvious that it’s a menstruation product, and it only takes half a day to dry indoors," Cheuk said.

With injection moulding, Cheuk believes that the expected total cost for the product – which is currently at a conceptual stage – should be around £3 for the whole set, including the washing parts and pads.

Other designs for refugees include portable kitchens by graduate collective Soup International, which were designed to be used by Southwark Day Centre for Asylum Seekers (SDCAS) for cooking purposes.