Grimshaw's "completely OTT" Sustainability Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai caused "significant unnecessary emissions"

A sustainable construction consultant has attacked Grimshaw Architects' Sustainability Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai for having an embodied carbon footprint of almost 18,000 tonnes – a figure that is double the recommended level for a building of its size.

Simon Sturgis, a consultant who advises on low-carbon construction, described the emissions as "very high" and said its design is "completely OTT".

Its spectacular steel canopy is responsible for "significant unnecessary emissions," said Sturgis, who runs low-carbon consultancy Targeting Zero.

"This design is not where you would start if you wanted to make a truly sustainable Sustainability Pavilion."

A lifecycle assessment sent to Dezeen by Grimshaw Architects shows that the construction process caused carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions of 1,050 kilogrammes per square metre, despite claims that the building would "set an example for sustainable building design".

Sturgis said the building is "comparable with a typical, average, new, multi-storey office building" in terms of its carbon footprint.

The pavilion, called Terra, has a built area of 17,000 square metres, meaning it has an embodied carbon footprint of 17,850,000 kilogrammes, or 17,850 metric tonnes.

Building is self-sufficient in energy and water

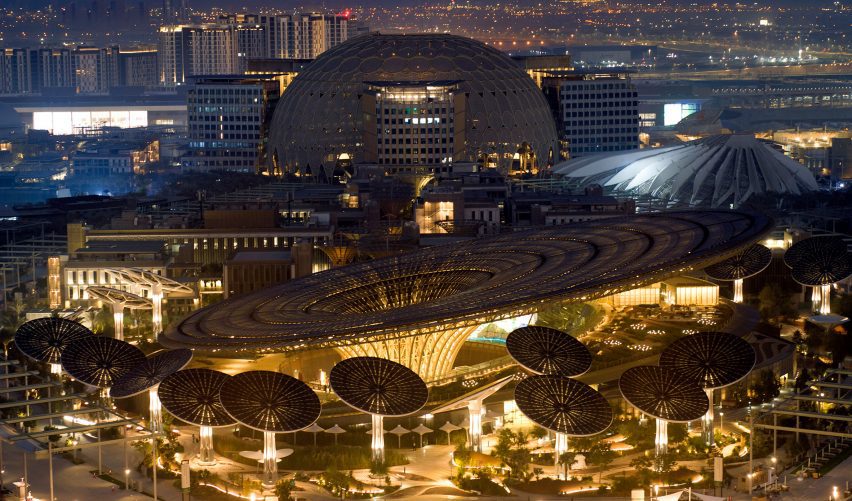

Grimshaw's pavilion is one of three flagship structures at Expo 2020 Dubai, which opened earlier this month, a year later than planned due to the pandemic.

Containing 6,000 square metres of exhibition space, it sits at the heart of the Expo's Sustainability District and promises to show visitors "how we can change our everyday choices to reduce our carbon footprint and environmental impact".

Made of steel, concrete and carbon fibre, the pavilion is shaded by a giant 130-metre-wide oval canopy topped with photovoltaics. Further photovoltaics are arranged on funnel-shaped structures surrounding the pavilion.

"The iconic Sustainability Pavilion, designed by the world-renowned Grimshaw Architects, has set an example for sustainable building design" explained the Expo's PR, who said the building is "net-zero for both energy and water."

This means that it does not rely on the electricity or water grid. Instead, it generates power via its rooftop photovoltaics and derives clean water by recycling wastewater, condensation and brackish surface water.

"The pavilion also uses cutting-edge water-reduction strategies, water recycling and alternative water," said the PR.

Grimshaw Architects chairman Andrew Whalley described the project as "an opportunity for the UAE to showcase innovations in energy efficiency, generation and water management for the region and deliver an aspirational message about the natural world and technology to a global audience."

Whalley added that the building was designed so that only minor alterations will be required to turn the building into a permanent sustainability museum at the end of the six-month expo.

"We expect this will be a 50-to-100-year building," he said.

The building has achieved LEED Platinum certification, which is the highest level available under the LEED sustainability certification system. It has also achieved LEED Zero Energy and LEED Zero Water certification.

LEED targets are "more nuanced and specific to the building design and usage requirements" than other standards that focus on embodied carbon, Whalley said.

However, LEED's scoring system is seen as being skewed towards rewarding operational performance rather than construction performance, despite the fact that embodied carbon accounts for around half the lifecycle emissions of a building.

Grimshaw prioritised decarbonisation of operational carbon

"When the building was originally designed in 2015, we prioritised the decarbonisation of operational carbon for the building, particularly as it was located in the Middle East," Whalley told Dezeen.

Operational carbon refers to emissions caused during the building's use, whereas embodied carbon refers to emissions caused during the construction process and its value chain.

"Embodied carbon evaluation is a relatively new field, and the measurements and benchmarks are very much in flux and can vary significantly by building type and region," he added.

"As knowledge of this area increases then benchmarks and targets are changing."

Whalley pointed out that the pavilion's embodied carbon footprint represents "a 41 per cent reduction from an equivalent new building in the region."

He added that the lifecycle assessment, which was carried out by Buro Happold, "includes an assessment of embodied carbon but also goes beyond that to consider other important potential material impacts such as ozone depletion and impacts on marine environments."

Pavilion's embodied carbon is double the target set by LETI

Sustainable buildings should aim for embodied carbon footprints of between 400 and 500 kg per square metre, according to the Embodied Carbon Primer published by the London Energy Transformation Initiative (LETI).

"Surely to be worthy of the name Sustainability Pavilion it should be in this zone and not double," said Sturgis.

By comparison, Sturgis pointed to Hopkins Architects' recent Living Planet Centre for the UK branch of the World Wildlife Fund, which has an embodied carbon footprint of less than 500 kg per square metre.

But Whalley argued that the building could not be compared to typical residential or commercial buildings and said the targets set by LETI are not appropriate.

"Terra is a very usage-intensive building and does not benefit from a regularity of form or economy of scale that a typical residential or commercial building does," he explained.

"The floor loading requirements are much higher than a residential building for instance, due to the potential uses of the spaces and levels of peak occupancy."

"Likewise, finishes and MEP [mechanical, electrical and plumbing] requirements are also required to be of a higher specification, which tends to lead to higher embodied carbon."

Sturgis said the steel-and-concrete canopy was "completely OTT".

"You have a huge density of steel and concrete structure at the roof centre, which is completely OTT in relation to the type of building it is trying to be," he said.

"This decision alone, to cantilever the roof, is directly responsible for significant unnecessary emissions."

Low-carbon materials "nothing special for a Sustainability Pavilion"

Sturgis said that the building's use of recycled steel and ground granulated blast-furnace slag to replace some of the cement "is normal for an office building but is nothing special for a Sustainability Pavilion".

"What about the use of sustainable materials like timber instead of all the concrete and steel?" Sturgis asked.

"This a standard 20th-century modernist design which is trying to be squeezed into a 21st-century sustainability pot," Sturgis concluded. "No amount of photovoltaics will fix that. The design needs to start from a completely different place."

Sturgis pointed out that Grimshaw Architects is a signatory to climate action group Architects Declare but said its design for the pavilion "suggests that they do not understand what this means. Where is the innovation fit for today?"

The built environment is responsible for 40 per cent of global emissions, with embodied carbon emitted by construction supply chains responsible for around half of those.

Next month's COP26 climate conference will see the embodied carbon emissions from the sector come under the spotlight for the first time at a dedicated built environment day.

Despite being an Architects Declare signatory, Grimshaw Architects is among hundreds of practices that have failed to sign up to the RIBA's 2030 Climate Challenge, which helps firms plot a path to designing net-zero buildings.