The passing of British architect Richard Rogers at the age of 88 marks the loss of one of the architects who shaped the past four decades, says Catherine Slessor.

"Ciao vecchio", said Renzo Piano, famously, when calling Richard Rogers to let him know that their fledgling practice had won the competition for the Pompidou Centre. "Are you sitting down?"

Vecchio – old man. The joke was that they were both in their late 30s – relative whippersnappers as far as architecture is concerned – but Rogers was four years older than Piano.

Now, with Rogers finally gone at 88 – molto vecchio – there is a melancholic sense of slow extinguishing, a point of light disappearing from a constellation of architects that shaped the last 40 years.

Rogers' star burned especially furiously, a stellar intensity illuminating leaden, dreary, exhausted post-war Britain. Born in Florence, scion of a cultured and well-connected Anglo-Italian family, he was transplanted to gloomy England in the late 30s, but his appetite for the food, cityscapes, atmosphere and general bella figura of mediterranean Europe remained perpetually undiminished.

Rogers' star burned especially furiously

There was no townscape problem that could not be solved by an infusion of cafe culture. An unrealised proposal to drape London's South Bank in an undulating glass roof would have had, in Rogers' view, the wholly desirable effect of blotting out the terrible English weather (and perhaps England itself) and create a microclimate, in both temperature and ambiance, approximating that of Bordeaux.

It's hardly surprising then that France, rather than England, formed a receptive crucible for the building that changed everything, the preposterous Pompidou Centre. I first saw it in 1982, when it was still relatively pristine, a hectic, eviscerated, hell-raising cenobite, gaudily flashing its candy-coloured guts to the world.

Back then, it was operating as Rogers and Piano intended, the free, zigzagging escalators bearing you skywards in a slow, ecstatic swoon to admire the best artwork of all, the aerial tableau of Paris, while in the parvis below, buskers straight out of central casting worked the crowds. Nobody actually went in.

Decades on, this idealistic conception of civic generosity, always appealing to the better nature of the city has been lost in the paranoia of modern security and creeping privatisation of the public realm.

Moreover, like all high-tech buildings, the Pompidou's maintenance regime is an increasingly huge and Sisyphean challenge. Since it opened in 1977, the Pompidou has cost more to maintain than build, and earlier this year it was announced that it is to close for four years from 2023 for yet another mammoth overhaul.

For Rogers, however, it remains his breakthrough project, turbo-charging a career that had hitherto been confined to pottering about with houses for in-laws.

Creek Vean in Cornwall, designed with Team 4 for his then father-in-law Marcus Brumwell, who sold a Mondrian to pay for it, gave little sense of what was coming, as the confluence of Victorian engineering puissance and Archigram's provocations slowly but surely aligned.

Rogers' vision of high-tech found its moment and its niche

Untainted by associations with modernism, at that time quietly lumbering to its unlamented grave, or the emerging pastel ironies of postmodernism, Rogers' vision of high-tech found its moment and its niche, adopted as the "progressive" style du jour by banks, museums and airports.

In theory, it was neutral, agile and rational, espousing kits of parts and infinitely flexible spaces, but in practice it could be as phantasmagorically fiddly as any German rococo church, memorably exemplified by the Lloyd's building, a self–professed "cathedral of commerce".

Again, it's hard to overestimate the impact of Lloyd's when it was completed in 1986, emblematic not just of a new and daring kind of architecture, but of a City exploding in a post-Big Bang frenzy following Thatcherite deregulation.

Though in a telling coda, the Lloyd's management insisted on retaining their 18th–century Committee Room, designed by Robert Adam for the 2nd Earl of Shelburne, reconstructed like a stage set or comfort blanket within their new high-tech home, possibly to protect against what Owen Hatherley has magisterially described as: "pure hedonism, architecture with all the crackle and complexity of a Detroit techno track".

Some sense of the distance travelled in the intervening decades can be conveniently apprehended by the Cheesegrater just across the road from Lloyd's, completed in 2014, bigger and duller, rococo fiddles long flattened out, yet still bearing the Rogers imprimatur with its perky yellow lift shafts.

Rebranded as Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, reflecting a carefully managed succession, the practice is now ensconced halfway up the Cheesegrater, an abrupt experiential contrast from its long-standing and more languorous riverside berth at Hammersmith, next to the famous River Cafe, which started life as the staff canteen. Ennobled in 1996, Rogers took the title Lord Rogers of Riverside.

An especially accomplished example of how to humanise a profoundly alienating building type

This is not an original observation, but there is a certain irony in high-tech so evangelistically espousing the advantages of industrial prefabrication and spatial flexibility, rapidly congealing into a bankable and biddable style for a limited cadre of the institutional elite.

Rogers himself was astute enough to understand this, and his mid-career output – the beehive pods of Bordeaux Law Courts and rippling manta ray roof of the Welsh Senedd – showed a certain softening and maturing of the original 'toys for the boys' aesthetic. Barajas Airport, which won the Stirling Prize in 2006, is an especially accomplished example of how to humanise a profoundly alienating building type, its chromatic structure guiding passengers through the airport labyrinth.

By contrast, Heathrow's Terminal 5 suffered from being bogged down by a 20-year public enquiry and as a result felt stodgy and dated on its eventual completion.

Other less successful projects would have to include the Millennium Dome, a village marquee on steroids that the public has now grudgingly taken to its bosom as a concert venue, and the slick silos of luxury flats at One Hyde Park and Neo Bankside, hyper-rich blandness personified, which have all the depressing hallmarks of a large firm on cruise control.

He grasped that architecture is nothing if not a social art

Typical of his expansive approach to practice, Rogers also turned his hand to engage in policy-shaping as the London mayoral advisor between 2001 and 2008. In assorted manifestos for architecture and urbanism he made the case for sustainability and the high-density city, attempting to inculcate a sense of wider, better possibilities.

Though there were obvious contradictions in his racking up of a largely institutional client list, he grasped that architecture is nothing if not a social art.

And, as the built environment is dragged down to the level of mindless 'Building Beautiful' sloganeering and bureaucratic cheeseparing by the present Conservative administration, such a genuinely engaging and galvanising presence will be missed. Days after Rogers' death, Lloyd's ceremonial Lutine Bell was rung once, signifying the loss of a great ship. Ciao vecchio.

Catherine Slessor is an architecture editor, writer and critic. She is the president of architectural charity the 20th Century Society and former editor of UK magazine The Architectural Review.

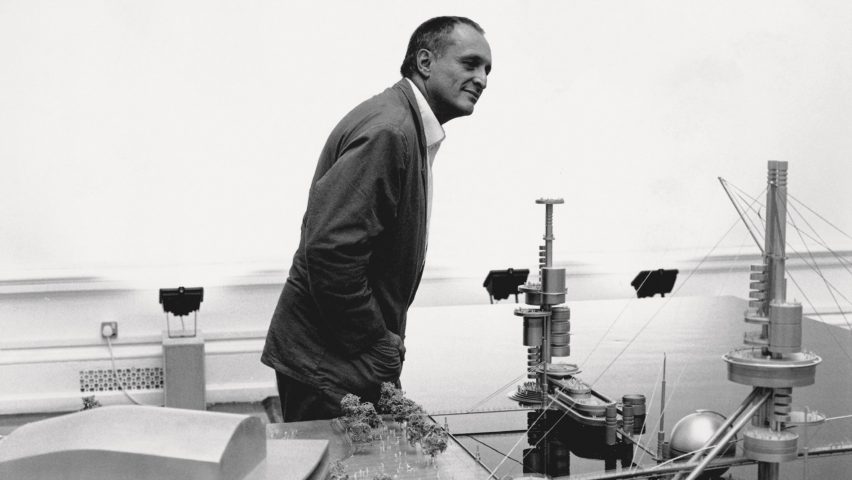

The photograph is courtesy of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners and shows Rogers at the "London as it could be" exhibition in 1986.