Framework develops modular laptop that users can fix and upgrade themselves

American technology company Framework has designed a laptop with modular components that can be repaired and replaced to increase the product's lifespan while reducing e-waste.

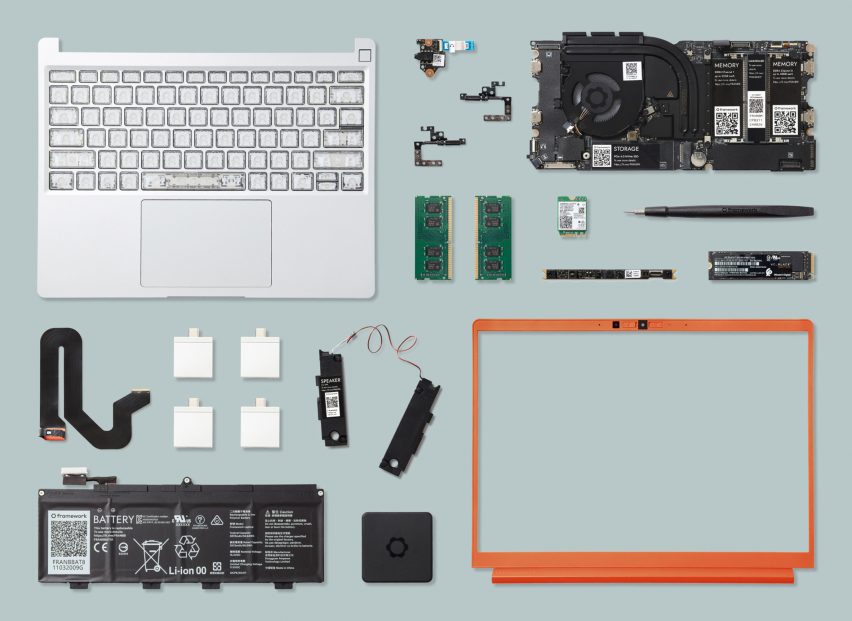

The Framework laptop is available in either a preassembled or a DIY version that customers can assemble themselves. It comes with a screwdriver and spudger to allow owners to easily customise, upgrade and repair their device.

Individual components such as the motherboard can be repurchased, reused or broken down and recycled, to help facilitate a more circular economic system.

Framework CEO Nirav Patel said the company's ultimate aim is to tackle the mounting problem of electronic waste.

"We've gone from 44.4 million tonnes of e-waste per year in 2014 to 53.6 million tonnes in 2019," he told Dezeen. "As an industry, we can't keep moving in this direction."

Rather than just focusing on recycling, Framework hopes to combat this issue by helping consumers to generate less waste and making products that last longer than traditional mass-market devices, which Patel describes as "disposable one-offs".

The lightweight laptop, which is the brand's debut product, features a 16-millimetre-thick, 13.5-inch screen housed inside a casing made from 50 per cent post-consumer recycled (PCR) aluminium.

Framework's Expansion Card system allows buyers to customise the laptop with their choice of ports, from USB to HDMI, which can sit on either side.

By loosening five small screws on the underside of the laptop, the keyboard section can be removed to reveal the device's insides.

The laptop's 55-watt-hour battery and motherboard can then be taken out and repaired. Alternatively, the motherboard can be replaced and reused as a single-board computer (SBC) for other DIY projects.

Each component is emblazoned with a QR code that directs users to step-by-step instructions for repair or replacement, as well as a webpage where they can order the spare part from Framework's marketplace.

Currently on display as part of the Waste Age exhibition at London's Design Museum, the laptop is one of a growing cohort of devices, including the modular Fairphone, that recognise consumers' "right to repair".

"We believe each consumer should have the fundamental right and ability to repair any product they purchase," Patel explained.

"We all have that drawer of shame of devices that are broken or have dead batteries or couldn't get that latest software update. None of us want that, and the right to repair is an essential part of solving it."

Both the European Union and the United Kingdom have passed some version of the right to repair into law, but laptops and smartphones have so far been excluded from this kind of regulation.

As a result, Patel says major technology companies have gotten away with doing the bare minimum.

"We are seeing consumer demand and regulatory pressure starting to push some of the lowest hanging improvements, like Apple's recent announcement of making some replacement parts available to repair shops and end consumers," he explained.

"Big companies aren't in the habit of making changes to their products that risk reducing revenue. So realistically, deeper modularity requires business model transformation to align the incentives around product longevity."

All photographs are courtesy of Framework.