Deconstructivist architecture "challenges the very values of harmony, unity and stability"

Deconstructivism was one of the most significant architecture styles of the 20th century with proponents including Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid and Rem Koolhaas. This overview by Owen Hopkins kicks off our series exploring the movement.

For most of the 20th century, the experimental, the innovative and the new had driven architectural culture forwards, but by the late 1970s postmodernism had it pushing in many different directions: back as well as forwards, maybe sideways too – or even just staying still.

The emergence of deconstructivism – an ungainly portmanteau of the mid-to-late twentieth-century philosophical movement, deconstruction, and 1920s Russian constructivism – suggested that the avant-garde's apparent demise may have been rather exaggerated.

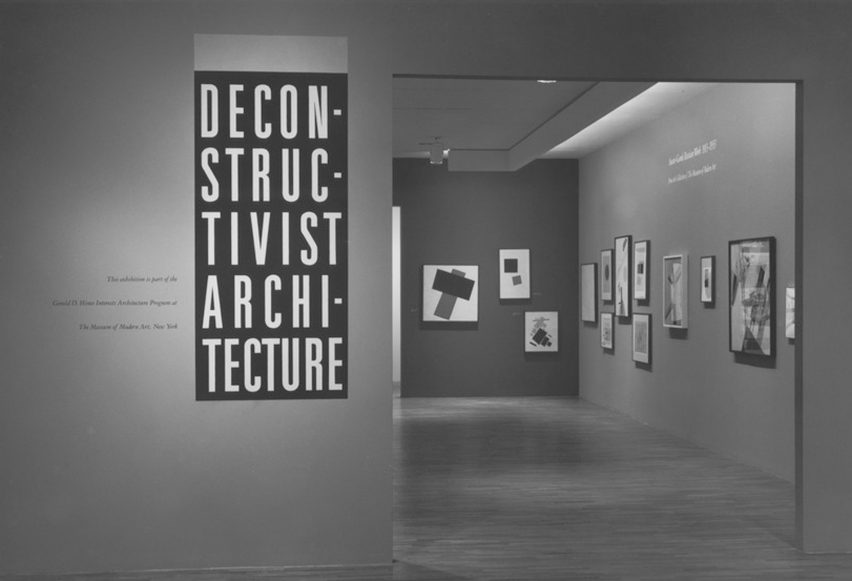

This at least was the implicit contention of Philip Johnson in the preface to the catalogue of the seminal Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition held at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1988, where, in collaboration with Mark Wigley, he brought together seven architects whose work, they contended, "shows a similar approach with very similar forms as an outcome".

Those seven were Gehry, Hadid, Koolhaas, Peter Eisenman, Daniel Libeskind, Bernard Tschumi, and Coop Himmelb(l)au.

All global stars today, but back then, with the exception of Gehry and Eisenman who were already established – if not yet establishment – figures, young and all decidedly radical.

Johnson had, of course, been here before, as curator of the seminal 1932 Modern Architecture exhibition at the same venue, which hailed the modern movement as the "new style" of the modern age.

Half a century later, however, he was at pains to point out that in contrast to the modern movement's "messianic fervour", deconstructivist architecture "represents no movement; it has no creed".

A fuller exposition of deconstructivism's origins and meaning Johnson left to his collaborator. For Wigley, "deconstruction gains all its force by challenging the very values of harmony, unity, and stability, and proposing instead a very different view of structure: the view that the flaws are intrinsic to structure".

"A deconstructive architect", he continued, "is therefore not one who dismantles buildings, but one who locates the inherent dilemmas within buildings."

Deconstructivism was, in his view, not a new avant-garde emanating from the margins, but constituted a "subversion of the centre", thus posing a challenge to all of architecture, old and new.

This, however, was hard to square with deconstructivism's embrace of the abstract, highly fragmented visual language of avant-garde Russian constructivism.

Exemplified in the work of El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, constructivism rejected all existing formal and compositional precepts in order to bring into existence a new architecture that would not simply reflect the revolution but would help further it.

With a few notable exceptions, the constructivists were largely confined to "paper architecture" before their suppression by Stalin in the early 1930s, with their work forgotten in the west until its "re-discovery" in the 1970s.

For young and aspiring architects looking for alternatives to modernism, but put off by postmodernism's perceived trivialities, constructivism was a revelation and it quickly became important in architecture schools, notably the Architectural Association in London under Alvin Boyarsky's direction, where several of the deconstructivist architects studied and taught in the late 1970s.

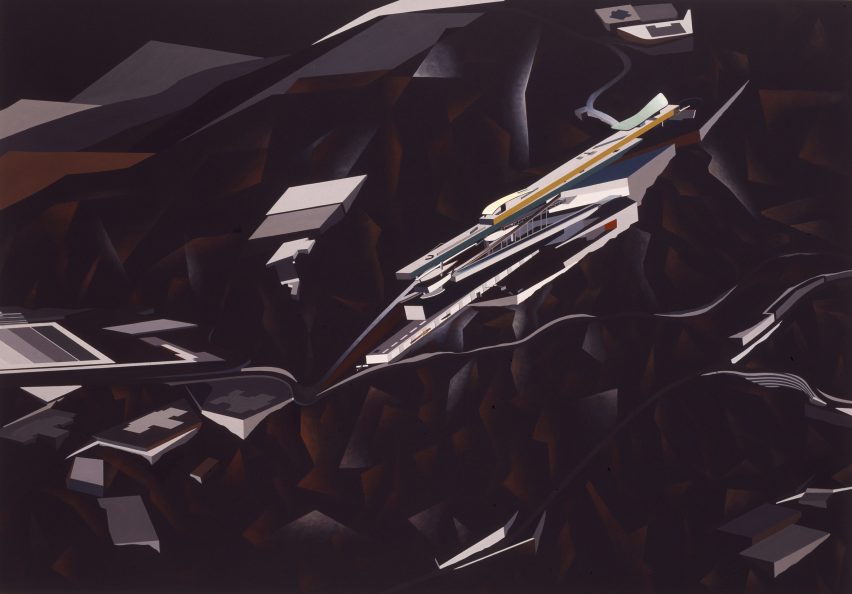

Of them, Zaha Hadid, was the one who most fully embraced constructivism as the basis for her own, highly distinctive formal language.

The MoMA exhibition featured her competition-winning proposal for The Peak, an upmarket club situated in Hong Kong's hills. All disorienting angles, vertigo-inducing viewpoints, and a structure emerging from and in spite of the topography, her paintings of the proposal offered a radical new vision of how architecture might be conceived.

Though constructivism was central to deconstructivism's formal language, it was far from simple revival or historicism. As Wigley pointed out, the "De" was all-important, bringing it in relation to deconstruction, a strand of post-structuralist thought closely associated with the French theorist Jacques Derrida.

Emerging in the 1960s, deconstruction took aim at the fundamental tenets of western philosophy and the binary oppositions and hierarchies that govern it.

Chief among these, for Derrida, was the primacy of speech over writing, and ultimately of signified over signifier. Instead, Derrida argued, meaning emerged dynamically in relationships between adjacent signifiers and he put forward new concepts, such as différance, which evaded binary systems.

Though arcane, largely inscrutable and by the 1980s already in decline, deconstruction was readily translatable to architecture and its own long-established binaries and hierarchies: order/disorder, form/function, rationality/expression and, perhaps most pertinently in the context of the 1980s, modern/post-modern.

In theory, at least, deconstruction offered a way to get beyond these; the question was how this might be manifest architecturally. The work of Tschumi and Eisenman, who had the closest relationship to deconstruction (as well as to Derrida himself), provided the clearer initial answers.

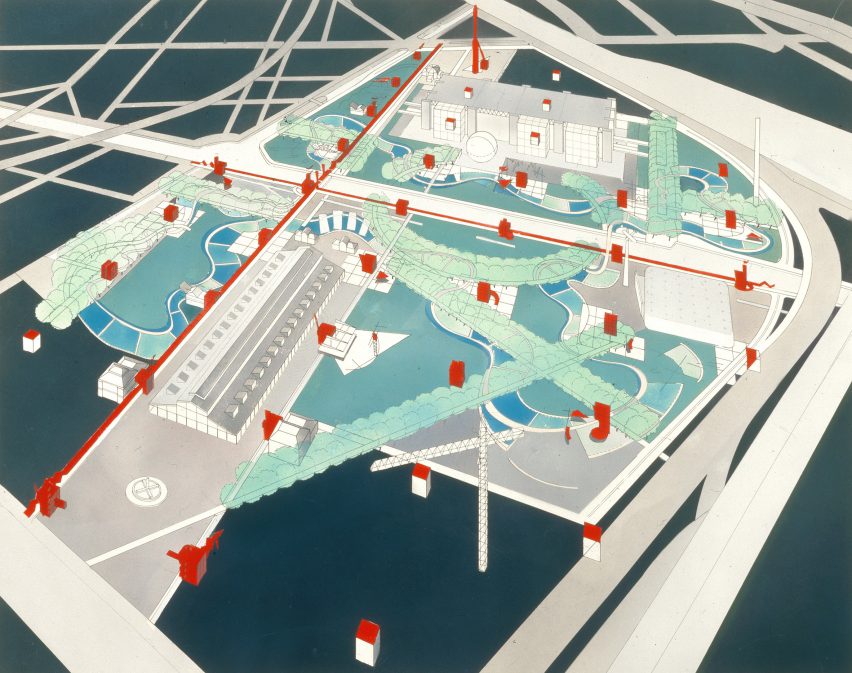

In retrospect, Tschumi's 1982–83 competition-winning scheme for the Parc de La Villette in Paris is the defining deconstructivist project.

Rejecting the age-old opposition between park and city, and beyond that between culture and nature itself, Tschumi conceived three ordering systems which he superimposed onto the site to generate a series of gardens, galleries and red steel follies.

The latter looked like a cross between constructivist agitprop structures and Anthony Caro sculptures – mash-ups of familiar architectural forms yet with no fixed referents.

At almost the same time, Eisenman was working on the Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University.

Here, Eisenman layered the mismatched grids of the university campus and surrounding city to generate series of fragmented forms which are sliced and spliced in ways that turn our expectations of how buildings are composed and structured on their heads. The result was uncanny and unsettling.

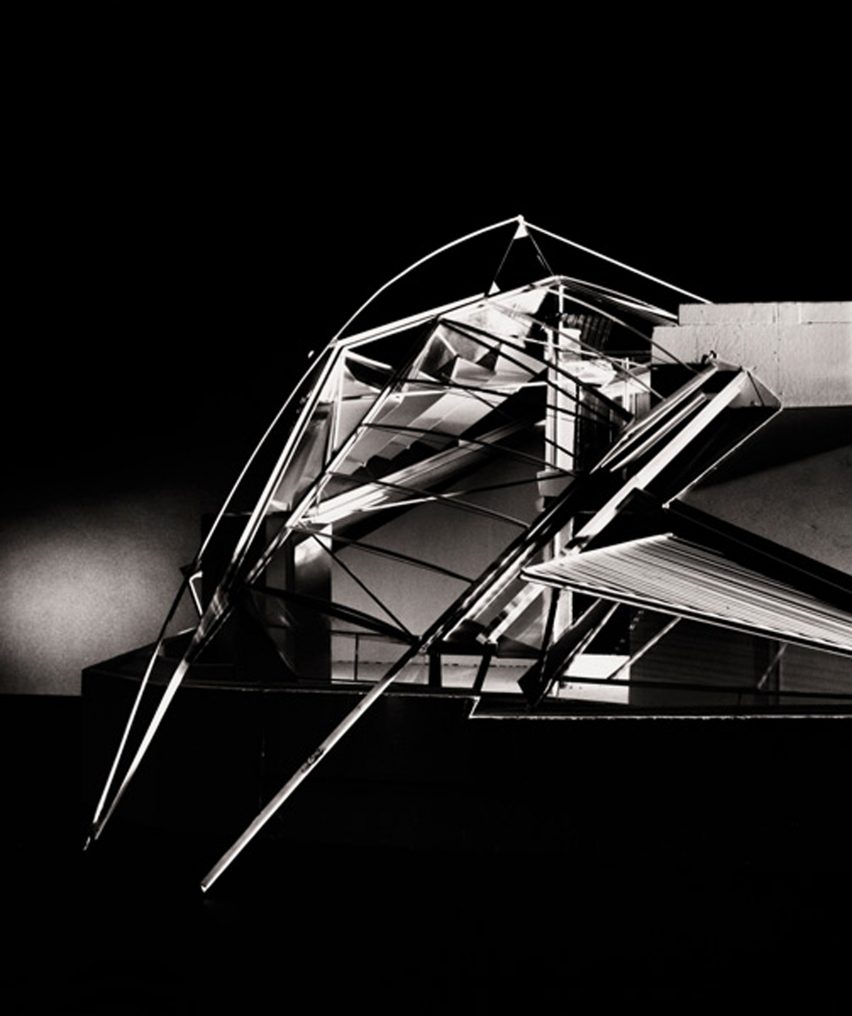

Something similar could also be said of Coop Himmelb(l)au's rooftop remodelling of a townhouse in Vienna, also included in the exhibition.

A jagged tangle of form and structure emerges from the roof of the townhouse, whose "stable form", the catalogue vividly describes, "has been infected by an unstable biomorphic structure, a skeletal winged organism which distorts the form that houses it".

Of all those featured in the exhibition, this project most clearly articulated the way deconstructivism sought to subvert not just the architecture of its own moment – as most avant-gardes tend to do – but all periods and styles. But to what end?

After all, postmodernism had absolved architects of adherence to modernism's social mission, something which deconstructivism did not challenge.

Instead, its radicalism was aimed at architecture itself, seeking to subvert its foundational formal and structural tenets with an intensity and vigour spurred paradoxically by its implicit acceptance of the new bounds of architecture's remit.

Put simply, if form-making was all that was left for architecture after postmodernism, then deconstructivism just ran with it.

That is not to say it was never anything more than an intellectual or a formal excise.

Libeskind's Jewish Museum in Berlin – his first built structure – demonstrated how deconstructivism could invoke history, memory and emotion in powerful and profound ways.

Zigzagging across its site, the museum's design is partly iconographic – recalling an abstracted Star of David – and indexical too, with axes radiating out to addresses of Jewish families murdered in the Holocaust.

With wound-like openings perforating its envelope, structure intersecting volumes and vice versa and vertical voids appearing unexpectedly, the building recasts our expectations of what architecture can be – and in doing so offers a haunting reflection on Jewish civilisation and Nazi attempts to destroy it.

Every avant-garde becomes mainstream after a while and though deconstructivism was in a sense architecture turned in on itself, external factors – economic and technological – would shape how it played out in 1990s and 2000s.

Though deconstructivism was conceived in an analogue world, it was realised in a digital one, allowing what was once unbuildable to be realised and, in turn, fuelling further formal experimentation.

Just look, for example, at the leap in scale and complexity between Gehry's Santa Monica house featured in the exhibition and the Guggenheim in Bilbao, perhaps the defining deconstructivist project, which was famously designed using software developed for fighter jets.

The Guggenheim was also the project that launched the age of the architectural icon which saw cities and even nations realise the importance of architecture in shaping their image and improving their economic fortunes.

And, of course, deconstructivism's outlandish and by definition one of a kind forms, coupled to its association with globetrotting starchitects – who the exhibition's protagonists all subsequently became – was the gift that kept on giving.

Despite Koolhaas being the person the one who least fitted in the group of seven original deconstructionists, or perhaps because of this, his CCTV building in Beijing took the age of the icon to its logical conclusion.

One of the oddly recurring themes of twentieth-century architecture is the way that everything Philip Johnson touched suddenly lost its vitality: the modern movement, postmodernism, and arguably also deconstructivism.

Looking back, it is startling how quickly deconstructivism's radicalism evaporated once its architects started to build at scale. Once it became necessary to compromise with gravity and the pragmatics of construction, the zest and vigour of the drawings – wonderfully manifest in the exhibition – gave way to frequently heavy, ungainly structures.

What's more, it exposed the movement's inherent weakness in its rather literal translation between theory and built form.

We certainly do have deconstructivism to blame for the still pervasive notion that a building must manifest a theory of some kind to be taken seriously. The irony is that, as pure form-making at its most thrilling, deconstructivist architecture is far more convincing without it.

Deconstructivism is one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements. Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Eisenman, Gehry, Hadid, Koolhaas, Libeskind, Tschumi and Prix.

Read our deconstructivism series ›

Dezeen is on WeChat!

Click here to read the Chinese version of this article on Dezeen's official WeChat account, where we publish daily architecture and design news and projects in Simplified Chinese.