"There are far more radical forms of digital art than the cultural dead end of NFTs"

With a focus entirely on commercialism, NFTs are the most boring form of digital art being developed, writes Phineas Harper.

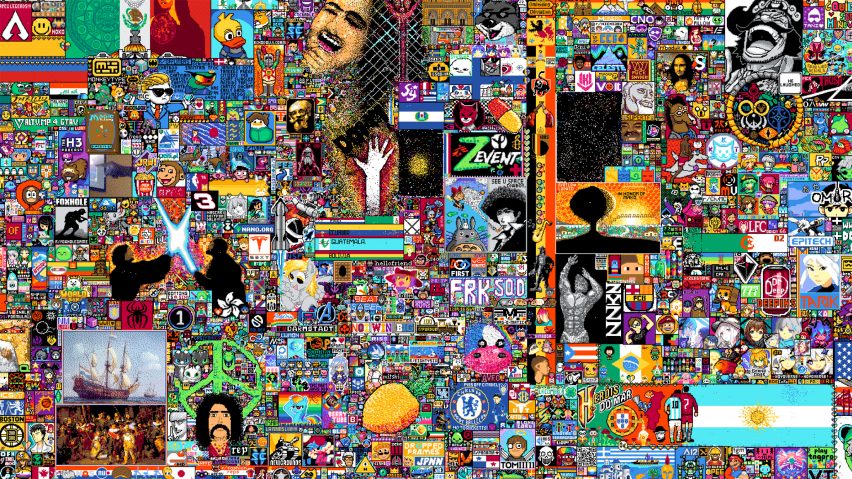

Last month, a collaborative online art project created on Reddit took the internet by storm. The vast interactive artwork, called Place, allowed anyone to lay coloured tiles on its enormous canvas one pixel at a time. Each user was only able to add a single tile once every five minutes.

Working alone it was impossible to design anything substantial, so Place users collaborated in enormous decentralised teams, coordinating their tile placement through self-organised online communities. The result was a million-pixel battleground in which rival factions jostled for their preferred artworks to prevail.

Place is a highpoint in the history of internet art

National flags, cultural icons, memes and even Herzog & de Meuron's Hamburg Elbphilharmonie were drawn and then overwritten by competing online factions.

Place is a highpoint in the history of internet art. Its technicolour vitality flows from the thousands of people who contributed. Free and open, the project perfectly expresses the possibilities of art in the age of the World Wide Web.

Yet in recent months a very different kind of online art has taken up headlines – one that derives its value not from sharing, but from owning: Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs). An NFT is simply a unique chunk of data, like a digital certificate, whose ownership can be sold and verified using an online public ledger called a blockchain.

By connecting a media file like a jpeg, gif or video with its own certificate, it becomes possible to trade them. The media itself is not sold but the digital certificate linked to it can switch hands for as much as buyers are willing to pay.

If you can convince enough people that a certificate linked to a piece of digital art you made is valuable then it becomes possible to make thousands of dollars flogging it in one of the numerous NFT marketplaces. Many celebrities, designers and artists have launched NFTs linked to their work, including Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst. Even beleaguered British chancellor Rishi Sunak has got in on the action by asking the UK treasury to create an NFT.

Ownership is merely a clerical add-on to the practice of art making

Big names and big sums, combined with global lockdowns that pushed many to adopt a more digital existence, have fueled international hype around NFTs propelling the burgeoning market to a value of $41 billion in 2021. This has prompted many to ask if NFTs are the future of art, but there are far more radical forms of digital art than the cultural dead end of NFTs.

Whether NFTs are here to stay or not, they are the most boring form of art ever created, centering value in nothing more than ownership.

Owning art is the least interesting aspect of art. A great artwork might be pioneering in its use of media, arresting in its formal composition, or rich with symbolism. It might ask profound questions of its audience or simply elicit a feeling among those who experience it.

Ownership, however, does none of these things. Ownership is merely a clerical add-on to the practice of art-making – the dull transaction necessitated by an economic system based on property owners harvesting value from the work of others.

The relative merit between NFTs worth millions and pennies is nothing but the promise of how much others might pay to own them.

In this sense, NFTs are the epitome of an industry lost to speculative investment – hallow avatars for late capitalism's broken relationship with the art and design worlds. They are the contemporary art market meeting its logical endpoint at which hype and hustle triumph over any other consideration.

Of course, the gallerists of Frieze and Basel have long used PR and spectacle to puff up the value of their collections, but the sheer banality of the NFT craze has reached a new level of tedium.

For all the designers who have successfully cashed in, many more will lose out

Digital art itself is not at fault. The aesthetic of many profitable NFT collections (gurning cartoon monkeys feature heavily) are certainly flat and derivative, but those qualities are not intrinsic to digital art. Digital art can, like Place, allow new forms of interactivity or, like remarkable computer games, immerse audiences in worlds as compelling as the best literature.

NFTs, however, explore none of this potential, retreating into the cultural cul-de-sac of mere ownership. Shills will say that NFTs are a new means for struggling artists to make money, but this narrow justification misses many key points.

First, those best able to profit from the NFT bubble are those already in command of substantial followings, like the famous musicians Grimes, Eminem and Snoop Dogg, who all recently released lucrative NFT collections. If there is cash to be made from issuing tokens, it will mostly flow to the already wealthy few rather than the struggling many.

Second, minting an NFT is not free, requiring makers to buy into cryptocurrency exchanges at their own risk like a pyramid scheme. For all the designers who have successfully cashed in on the hype machine, many more will lose out, predominantly those least able to do so.

Above all, NFTs erode the most radical and adventurous aspect of the internet: sharing. Sharing is a nourishing act of solidarity, fundamentally more enjoyable and resource-efficient than the kind of private, solitary ownership that consumerism promotes.

But every time something that could have been sold is shared, an opportunity to extract profit has been lost, and it is for this reason big tech and finance are cynically pouring resources into cryptocurrency innovations like NFTs.

As art, NFTs are boring beyond words, but as tools to commodify what was previously a digital commons they may be far more insidious – turning the internet from a place of sharing to a place of owning.

Phineas Harper is director of Open City and formerly deputy director of the Architecture Foundation. He is author of the Architecture Sketchbook (2015) and People's History of Woodcraft Folk (2016).

Dezeen is on WeChat!

Click here to read the Chinese version of this article on Dezeen's official WeChat account, where we publish daily architecture and design news and projects in Simplified Chinese.