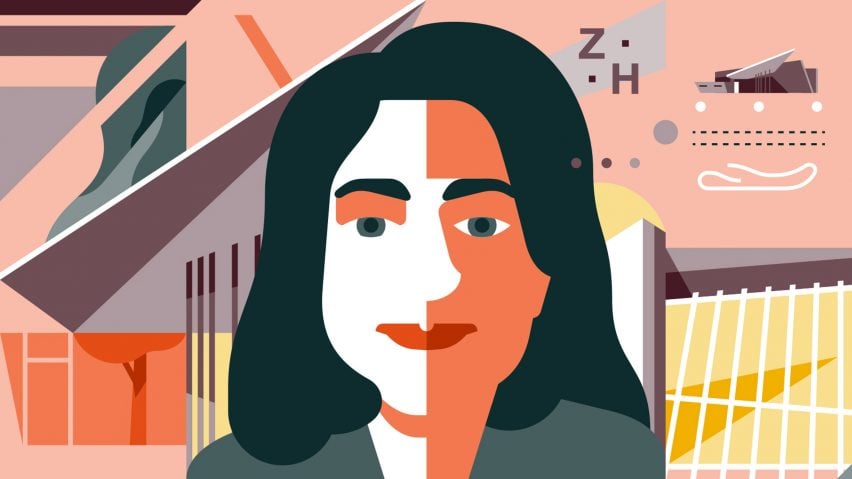

Continuing our series revitising deconstructivist architecture we look at the late Zaha Hadid, the "queen of the curve" who designed the Heydar Aliyev Centre and London Aquatics Centre.

As arguably the most successful female architect in history, Hadid pushed the limits of structure to new heights.

The defining moment for the late British-Iraqi architect came when in 1983, aged 32, she won the architectural competition to design The Peak private club in the hills of Kowloon, Hong Kong.

Featuring daring angles, vertigo-inducing views and gravity-defying cantilevers, all thrusting out from a "manmade mountain", Hadid's paintings of The Peak were a powerful display of the possibilities of deconstructivism.

Although never built, the scheme was testimony to what could be expected from the architect in the future.

It was this design that formed Hadid's contribution to the seminal Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1988, where she featured alongside Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, Peter Eisenman and Coop Himmelb(l)au.

Deconstructivism, as defined in the exhibition texts, referred to architecture that married the aesthetic of modernism with the radical geometry of the Russian avant-garde.

For Hadid, this approach was particularly significant; it afforded her the opportunity to explore the types of forms employed by the Russian structuralist painters she idolised, including Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin.

Inspired by Russian painters

This fascination began in the 1970s, while Hadid was studying at the Architectural Association in London.

The AA at that time was a hotbed of ideas, but Hadid was part of a rebellion calling for greater focus on drawing as a tool for conceptual development.

With the support of then-director Alvin Boyarsky – who remained a close friend up until his death in 1990 – she led the charge for a more radical approach to architectural expression.

"I found the traditional system of architectural drawing to be limiting and was searching for a new means of representation," Hadid wrote in an editorial for RA Magazine, accompanying a Malevich exhibition in 2014.

"Studying Malevich allowed me to develop abstraction as an investigative principle."

In Malevich in particular, Hadid saw painting as a means of capturing a sense of weightlessness, and using it to generate dynamism and complexity in architecture.

She demonstrated this in a thesis project, for which she adapted the form of a Malevich sculpture to create a design for a 14-storey hotel spanning the River Thames.

Faith in the power of progress

Hadid's childhood laid the foundations for this experimental spirit. She was born in Baghdad in 1950, daughter to progressive liberal politician Mohammed Hadid.

This was a time of radical modernisation and social reform in Iraq, with architects including Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius all working on projects in the capital. It was also a place where it was not uncommon for women to become architects.

"When I was growing up in Iraq, there was an unbroken belief in progress and a great sense of optimism," Hadid said in an interview with the Guardian in 2012. "It was a moment of nation building."

It was here that Hadid developed her love of architecture, inspired by the river landscapes and the fluidity with which they would merge with buildings and cities.

Hadid attended boarding school in England and completed a maths degree at the American University of Beirut before arriving in London to enroll at the Architectural Association (AA) in 1972.

After graduating, she briefly went to work for former AA tutors, Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis of OMA, before founding her own practice, Zaha Hadid Architects, in 1979.

From angles to curves

The success of The Peak paved the way for Hadid's first realised project, a private fire station for the Vitra furniture factory in Weil am Rhein in 1993.

Boasting shards of concrete at striking angles, its powerful composition pushed the limits of structural possibility.

Equally daring forms could be found in the projects that followed; in the twisting gesture of the Bergisel Ski Jump in Innsbruck in 2002, the floating volumes of the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati in 2003 and the clashing angles of the Phaeno Science Center in Wolfsburg in 2005.

Over time, the hard lines and sharp angles that defined Hadid's early work began to soften into sumptuous curves and undulating planes.

With long-term collaborator Patrik Schumacher, she began to fully explore the potential of parametric design software, earning the nickname "queen of the curve".

Among the most audacious examples are the MAXXI museum in Rome in 2009, the London Aquatics Centre in 2012 and the Heydar Aliyev Centre in Baku in 2013.

When challenged over the radical forms of these buildings, Hadid would hold true to her belief in complexity and fluidity in the built environment.

"People think that the most appropriate building is a rectangle, because that's typically the best way of using space," she said in a Guardian interview in 2013.

"But is that to say that landscape is a waste of space? The world is not a rectangle. You don't go into a park and say: 'My God, we don't have any corners'."

Misunderstood intentions

Hadid often didn't have it easy. Despite being awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2004, her career was overshadowed by a perceived notion that her buildings were overly complex and, as a result, overly expensive.

This led to the cancellations of what should have been two of her most significant buildings.

Her 1994 competition-winning scheme for Cardiff Bay Opera House – much like The Peak – was never realised, after nerves got the better of the trustees. More than 20 years later, in 2015, she was booted off the Japan National Stadium project following a dispute over projected costs.

It also took Hadid a long time to win a project in London, despite having made the city her long-term home. Her Stirling Prize-winning Evelyn Grace Academy in 2010 was the first of very few permanent buildings in the capital.

Yet Hadid always disputed the suggestion that her buildings were self-indulgent or wilful; in her RIBA Royal Gold Medal lecture in 2016, weeks before her death, she reiterated her belief in architecture as a tool for improving society.

"For me there was never any doubt that architecture must contribute to society's progress and ultimately to our individual and collective wellbeing," she said.

Hadid died on 31 March 2016, after suffering a sudden heart attack. Her achievements have been praised by some of the biggest names in architecture, with Koolhaas describing her work as "something fundamentally different" and Norman Foster praising her "great courage, conviction and tenacity".

But it is Peter Cook, a former tutor of Hadid's, that has best summed up the architect's legacy.

"If Paul Klee took a line for a walk," he said, "then Zaha took the surfaces that were driven by that line out for a virtual dance and then deftly folded them over and then took them out for a journey into space."

Deconstructivism is one of the 20th century's most influential architecture movements. Our series profiles the buildings and work of its leading proponents – Eisenman, Koolhaas, Gehry, Hadid, Libeskind, Tschumi and Prix.

Read our deconstructivism series ›

Dezeen is on WeChat!

Click here to read the Chinese version of this article on Dezeen's official WeChat account, where we publish daily architecture and design news and projects in Simplified Chinese.