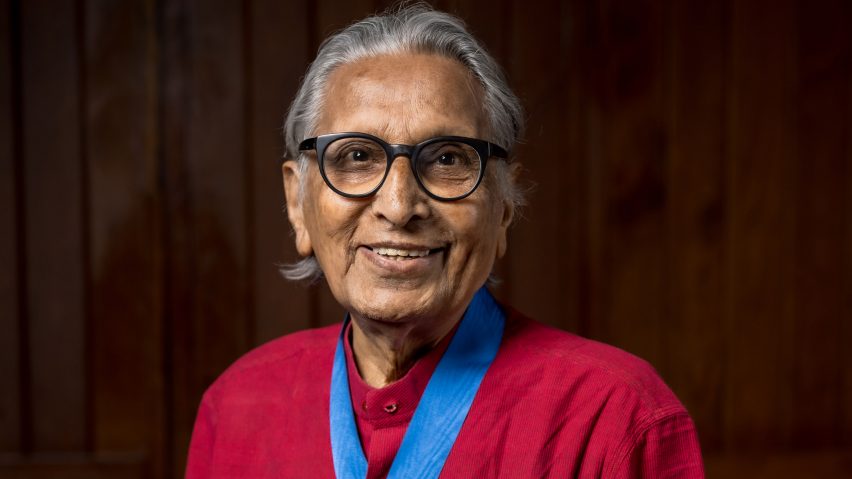

"True architecture is life" says RIBA Royal Gold Medal-winner Balkrishna Doshi

Architecture should seek to respond to human behaviour and not dictate it, says this year's RIBA Royal Gold Medal-winner Balkrishna Doshi in this interview.

"Design is accommodating lifestyles, merging with them," Doshi told Dezeen on a video call from his studio in Ahmedabad in western India.

"I'm not really saying that this is measurable – these things are all unmeasurable – but they are very, very important."

The veteran architect, now 94, was recently presented with the Royal Institute of British Architects' (RIBA) Royal Gold Medal, which is awarded annually to those who have shaped the "advancement of architecture".

Doshi, who has a portfolio of more than 100 built projects, including collaborations with his "gurus," the legendary architects Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, said he was "more than honoured and delighted" by the accolade.

RIBA president Simon Allford said Doshi was "the outstanding candidate" for this year's medal, "long deserving of the award". The only Indian architect to have previously won was Charles Correa, in 1984.

"There is something unique about Indian sense of space"

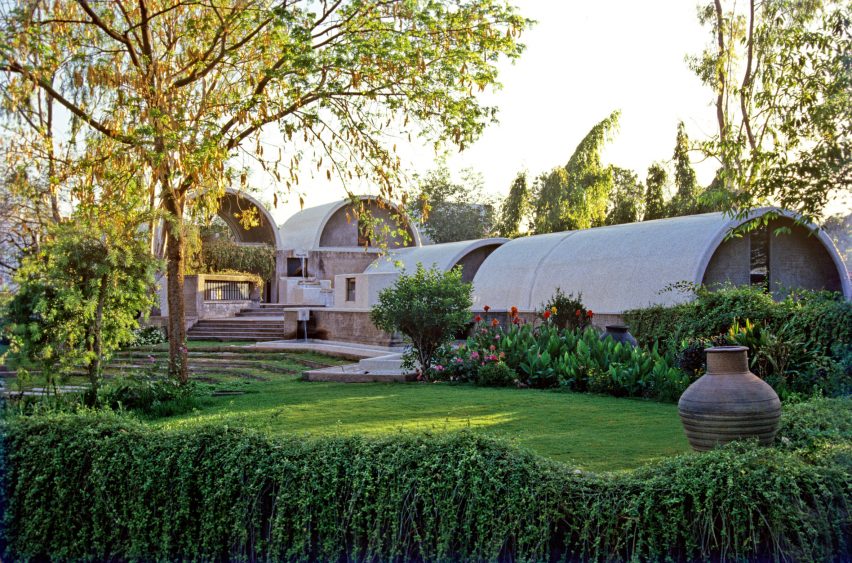

Doshi describes his own architectural style, which he still practises daily from his Ahmedabad studio, Vastu Shilpa Consultants, as "natural", attempting to fit seamlessly around people's lives.

His buildings place the modernist principles of Le Corbusier in a distinctly Indian context, steering away from shiny skyscrapers and instead responding closely to local traditions and climates.

"If you look at it saying that you are natural, you are obvious, you are merging in with the local surroundings, and if you are around a crowd in a building and you feel that this building sits very well with the whole mass of people with their different activities, perhaps that is the kind of buildings that I try to do," Doshi explained.

This approach is directly linked to the Indian national identity and culture, he asserts. Doshi, who won the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2018, is widely considered to have defined postcolonial Indian architecture.

"If you look at the villages and towns where people are naturally moving around, you will know that there is something unique about Indian sense of space, Indian sense of time, form, colour, texture, and even celebration," he said.

"[The] Indian way of life is encroaching things, overlapping things, adding new things all the time and changing themselves," he continued. "We are not the ones who design a space and think about that space as something which is sacred, but we think it's part and parcel of us. We are natural, we dress naturally, behave naturally, collaborate naturally."

Doshi summarises his philosophy in four words: "True architecture is life".

Over his 70-year career, he has become as revered for his teachings as for his designs. "You've created a school of architecture, literally and metaphorically," British architect Norman Foster said in his tribute to Doshi during the medal-presenting ceremony.

In 1962, Doshi founded the School of Architecture in Ahmedabad, now known as CEPT University.

"When I started the school, my first lesson was to talk about the way of life in India," he remembered.

"I took them [the students] to the Old City, saying, 'Let's walk through the street and the bazaar and the houses and just see what it is like'", Doshi said.

"And when they come back I say, 'Now tell me what kind of life do you think you want to do?' But not the other way around."

Throughout Doshi's own education, which saw him graduate from the JJ School of Architecture in Mumbai before studying further in London and beginning his career in Paris, he recalled that his "identity remained strong, with my own culture and my family".

He has spent his career, he said, "trying to really find out what is genuinely, or close to, an Indian feel" through his architecture.

"I was shocked by the way people were using Aranya houses"

One of Doshi's most celebrated schemes is the Aranya Low-Cost Housing complex in Indore, which won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1995.

Here, the Indian way of life led to the scheme evolving in ways he had not anticipated, Doshi reflects.

"The people really abused it, in the normal language," he said. "They added to the balcony, they added another floor, they added extra staircases and all the things which were convenient for them to use. And I was really shocked."

That initial horror gave way to an understanding that Doshi has carried with him since after interviewing some of the residents.

"I was shocked by the way people were using Aranya houses," he explained. "But then I saw that they were more happy than where I had designed something."

"And then it felt right that this is really how they live and they want to enjoy their life," he added. "So is architecture something exclusive, or is it inclusive? And I think I'm talking about inclusiveness of space and form and structure."

In his practice, Doshi says he tries to create buildings that open themselves up to this organic process of alteration.

But he rejects the suggestion that this is a form of modesty on his part. "No, it is not necessarily modesty," he said. "It is an awareness that I allow them an opportunity to transform, readjust and become natural."

The central challenge, he argues, is striking the right balance between fostering this evolution towards becoming "natural" and making sure buildings retain a sense of aesthetic order.

"Eventually it will be very chaotic, it will have no order at all," he said. "So the question I'm trying to [answer] is: how do I bring a subtle order which our social, cultural ethos talks about and then bring that into the spaces and forms and the kind of light and climate et cetera."

"Can I become an instrument of making that transformation happen in a reasonable way where there is still a part of aesthetics and a sense of beauty?" he continued.

"And I think that's what I'm trying to find out, so that we should not lose the aesthetic sense but heighten and create a unique aesthetic sense which merges with our lives."