Great Wrap is a clingfilm alternative made from waste potato peels

Australian biomaterials company Great Wrap has created a compostable bioplastic alternative to clingfilm that is made from waste potatoes.

Great Wrap film consists of starch extracted from potato peels mixed with other ingredients including used cooking oil and a starchy root vegetable called cassava.

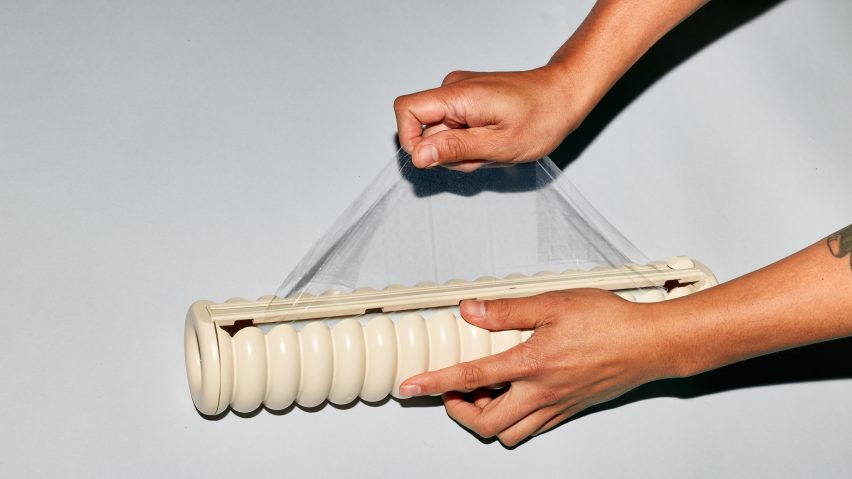

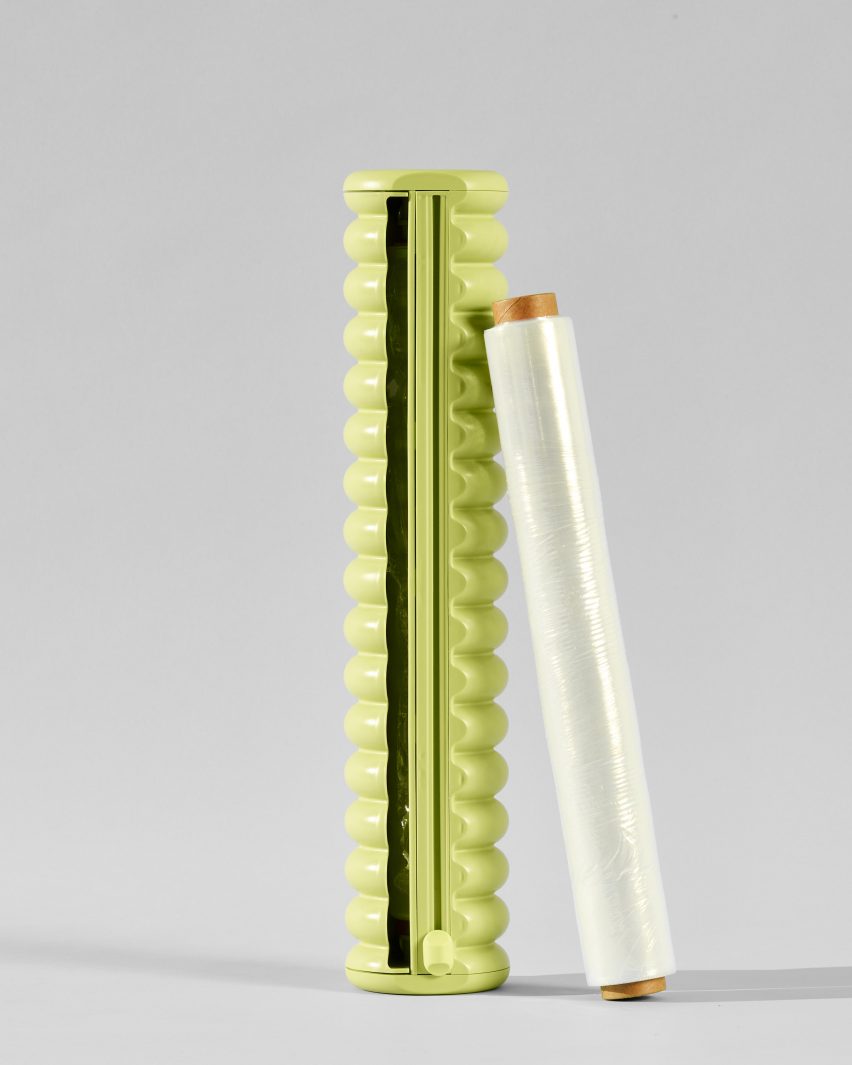

The transparent packaging, which comes in colourful recycled-plastic dispensers, has similar textural and performance qualities to petroleum-based plastic clingfilm, the company claims.

"The starch is extracted from the waste and then plasticised with a bio-based product," explained Great Wrap's co-founder and co-CEO Julia Kay.

"The thermoplastic starch (TPS) is then compounded with used cooking oil, cassava and biopolymer additives to change the polymer structure so that it is suitable for stretch film," Kay added.

"We then heat the compounded pellets to melting temperature and extrude a stretch film."

The biopolymer additives are necessary to change the polymer structure and make the material stretchy so that it can be used to wrap boxes and keep food fresh, much like traditional plastic clingfilm.

"We searched the market and the literature for materials that were compostable yet had mechanical properties that could stack up to the current petroleum-based films," Kay said.

"We then looked at formulating available bioplastics and processing them in such a way that the final properties were comparable to existing products."

When the Great Wrap has reached the end of its life, Kay says it can be composted in landfills or home composting systems, where tests have certified it will break down within 180 days.

"Great Wrap breaks down the same way as food scraps, into food and energy for the microbes in your compost," Kay explained. "It goes perfectly with your organic waste to be composted into rich nutrient soil, ready to be repurposed."

However, the material cannot break down in marine environments. In an effort to rectify this, the company has been working with researchers at Melbourne's Monash University to find out how it can convert potato waste into polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA).

PHAs are biodegradable polyesters, which are naturally produced by certain bacteria and can break down in oceans and other aquatic environments in less than a year.

"PHA not only achieves what our current formula already does but it will also break down in marine environments, leaving nothing behind," Kay said.

"We are currently scaling this system to pilot scale and in 2023 we will begin building our PHA biorefinery that will divert over 50,000 metric tonnes of potato waste from landfill every year."

The Victoria-based company sources its potato waste from a supplier in the US state of Idaho. As a result, the product's carbon footprint is much larger than it would be if the potato waste was sourced locally.

But the company is currently looking into local manufacturing options, especially ahead of its launch in the US later this year.

"As we grow, we plan to expand our network by setting up a facility in each new region we launch in, enabling us to use local potato waste and feedstocks from each area," Kay said.

Bio-based materials are becoming increasingly popular among designers as consumer awareness around the environmental impact of petroleum-based plastics increases.

Reykjavík design studio At10 recently developed a bioplastic meat packaging made from animal skins while design duo Doppelgänger created a bio-based version of polystyrene foam made from the exoskeleton of mealworms.

But designers including Charlotte McCurdy have suggested that designing bioplastics to biodegrade could actually be counterproductive in the fight against climate change, as the carbon that was stored in their plant-based ingredients could be released into the atmosphere or the ocean as they degrade.

The photography is by Shelley Horan.