Architecture studio Lemay has published a manifesto calling on Canadian studios to unite behind a more radical approach to design that reflects Indigenous values and takes responsibility for the country's abundant natural resources.

Penned by Lemay's research arm FLDWRK, the Manifesto of Canadian Design argues that architects, designers and researchers across the nation must re-evaluate the "characteristic humility of the Canadian ethos".

"No longer must we remain stagnant, modest, 'nice'," the manifesto reads. "The moment for us to rise as drivers of design has crystallised."

Canada is the second-largest country in the world and among the most abundant. But a majority of its resources, from oil and timber to aluminium and lithium, are currently exported for use elsewhere, according to Lemay's chief design officer Andrew King.

"We're almost neutered in the way we have been using the Earth," he told Dezeen. "We're almost saying okay, just take what we have and you can do anything you want with it."

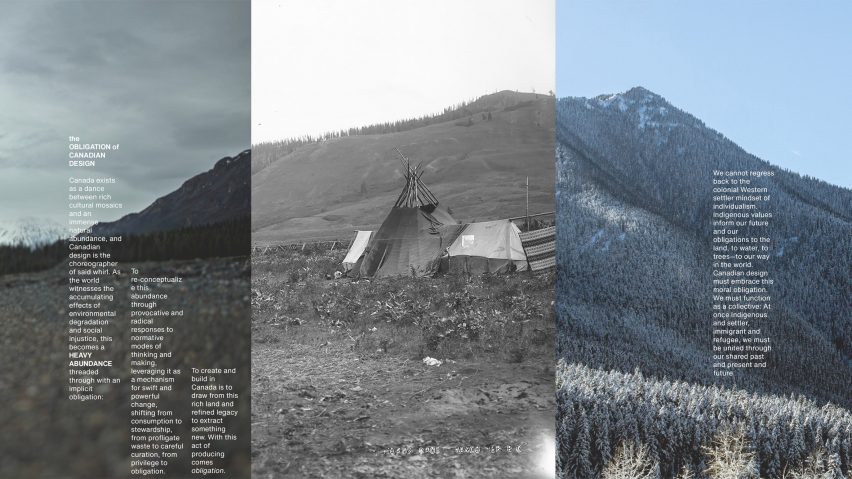

In light of the climate crisis and widespread environmental degradation, the manifesto argues that Canadian studios now have a duty to take on a more active stewardship role over their land, as modelled by the country's Indigenous communities.

"Canadian design has to be much more radical," King explained. "We have to un-fuck the processes in which we turn our abundance into garbage."

"Indigenous values inform our future"

The Manifesto of Canadian Design was released in time for the UN's COP15 biodiversity conference, concluding in Montreal today. But it was originally born out of a live panel talk hosted by Dezeen, in which King outlined the need for studios to work together to form a cohesive "pan-Canadian" design identity.

This should be promoted around the world with support from policymakers, he argued, to distinguish Canada from its southern neighbour the USA and establish it as a global leader in sustainable design.

"I'm hoping broadly, internationally, Canada starts to be understood as a different place, as a place that has enough thoughtfulness, design talent, energy and commitment to actually frame a design language around what it has," King explained.

"And it doesn't have to accept a Bjarke Ingels building in every city, it doesn't have to accept timber-frame technology from Norway," he added. "It actually has these things and can actually drive itself moving forward."

The manifesto is divided into four sections and begins by outlining the duty of care that comes with Canada's "immense natural abundance", which has long been championed by its First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities.

"Indigenous values inform our future and our obligations to the land, to water, to trees – to our way in the world," the manifesto reads. "Canadian design must embrace this moral obligation."

Design should be treated like fine wine

In practice, that means designers will have to start sourcing locally and interrogating where their materials come from, making these resources the starting point of their work rather than simply an afterthought, King explained.

"We tend not to really worry about where materials come from, which communities they affected and which landscapes they destroyed," he said. "We can't mine our resources, send them to Brazil to be processed and then not understand that that's what's in the electric cars we're driving around."

By changing the way that products and buildings are designed, King says architects and designers can highlight these connections in much the same way that a protected designation of origin highlights the provenance of certain foods and drinks.

Ultimately, he argues this could help Canada to use its resources more locally and responsibly.

"With more precious exotic woods or even wines, we understand that they emerge from a particular place," he said. "Wine emerges from the terroir, from the soil and it gets identified with that place."

"I think there has to be a kind of obligation to create those links through design," he added.

Canadian design is a "lingua franca"

The manifesto culminates in a call for a "radical future for Canadian design", urging architects and designers to create projects that are not just climate resilient and "of the land" but also radically diasporic and inclusive.

Because at its heart, King says Canada is distinguished by its ability to reconcile a range of different immigrant and Indigenous cultures, rather than having a hugely distinctive culture of its own.

"I'm going to get in trouble if this gets published," King said. "But the idea of Canadian food, Canadian wine – these cultural constructs are somehow not as rich as we would hope."

"But what we do have is a much broader encyclopaedia of rich and evolving cultural structures. And we have to embrace those."

With this in mind, the manifesto calls for Canadian design to be a "lingua franca" – a common language that can be used to communicate between groups of people with different mother tongues.

"Canadian architecture must be home to all," the manifesto concludes.

A growing number of architecture projects across Canada are already demanding that local communities be reflected in their public buildings.

In Vancouver, Herzog & de Meuron is working with four Indigenous artists to develop a woven metal facade for a major new art gallery, while further north in Terrace, British Columbia, HCMA collaborated with the Tsimshian Kitsumkalum First Nation on the design of student housing for Coast Mountain College.