"An architect who only designs buildings is like a doctor who only prescribes paracetamol" says ProxyAddress founder

Architects have a duty to use their skills to help solve societal problems even if it means thinking beyond designing buildings, ProxyAddress founder Chris Hildrey tells Dezeen in this interview.

British architect Hildrey founded ProxyAddress, a social enterprise that gives people experiencing homelessness a fixed address, in 2018.

"It's about removing potential obstacles"

The system works by virtually duplicating existing addresses and allocating them to people lacking a stable home, enabling them to apply for jobs, bank accounts and social security among other services.

"It's about removing the potential obstacles or stigma and allowing people to be judged on their merit," Hildrey explained.

"They're looking to just get a bunk up onto the ladder and regain their independence, and so that's what we're trying to do."

A pilot of the concept conducted between 2020 and 2021 in Lewisham, south-east London resulted in 95 per cent of ProxyAddress users escaping homelessness within six months.

"We went into this expecting 25, 30, maybe 35 per cent of people going through the pilot to end up not being homeless by the end, so it was astounding," Hildrey said.

ProxyAddress is now seeking to test the system in five other areas this year, beginning with a second trial in Glasgow set to kick off in the spring.

Hildrey argues that ProxyAddress is an example of how architects can look beyond simply designing buildings to have a positive impact on the built environment.

"I wouldn't say it's an obligation, I would say it's more than that," he told Dezeen. "I would say it's a duty of an architect."

"I think as an architect you can feel like you have less agency than you perhaps do, but I think it's about how you choose to practice, because traditional practice will constrain you."

Hildrey, who also founded the London-based Hildrey Studio, came up with the idea for ProxyAddress while researching homelessness as designer in residence at the Design Museum.

Having previously worked at large firms like Foster + Partners as well as smaller studios, he said he had come to feel that architects' skills are often not fully exploited.

"I found the transition from university to practice a bit strange, because at university you train in so many skills, but the one thing you never do is actually get a building built," he said.

"And then you come out of university, and the only thing you're expected to do is get buildings built, and a lot of the skills you spent seven-plus years developing kind of go to the wayside."

This paradox is leading to "missed opportunities" for architects to help find solutions to issues in the built environment and beyond, he argues.

"An architect who only designs buildings is a bit like a doctor who only prescribes paracetamol. There are different issues that clients come to you with, and sometimes a building is the right solution, but sometimes it's not."

"And for me, that narrowing of the remit of the architect from university to practice, where you're only expected to do one type of output, was a lot of missed opportunities in terms of ways in which our architects could actually start to influence the built environment positively."

Applying "design methodology" to homelessness

Standard architectural solutions to homelessness – such as designing low-cost temporary accommodation – fail to address the root causes of the problem, he contends.

"In terms of the stock responses, like 'let's build a village of shipping containers to house people in homelessness', I could spend half an hour dismantling that whole approach to homelessness because it's very lax in its response."

Hildrey had previously looked into methods of architectural practice not related to buildings, "especially how that can work in areas where buildings aren't necessarily the easiest or most direct way to have impact".

"To me, designing stuff that looks nice while people have nowhere to live is just a struggle," he said. "I mean, it's like polishing the top of something when the bottom is falling out. You need to fix the bottom."

Homeless people in the UK face a catch-22 situation wherein their lack of an address prevents them from applying for jobs, getting a bank account or accessing other services that could give them a route out of destitution.

Hildrey said he was able to rethink the addressing system that locks out homeless people by applying "design methodology to the problem".

"I went into meetings about quite dry topics, and they'd see me come in and I'd be introduced as a designer or an architect, and I could sense a little eye roll of like, 'here we go'."

"Because I think a lot of people expect designers to be, you know, 'well, this is my version of the world I want to happen, what are you going to do to make it happen?' Whereas actually that's just bad design. A good designer goes in and tries to understand their systems better than they do."

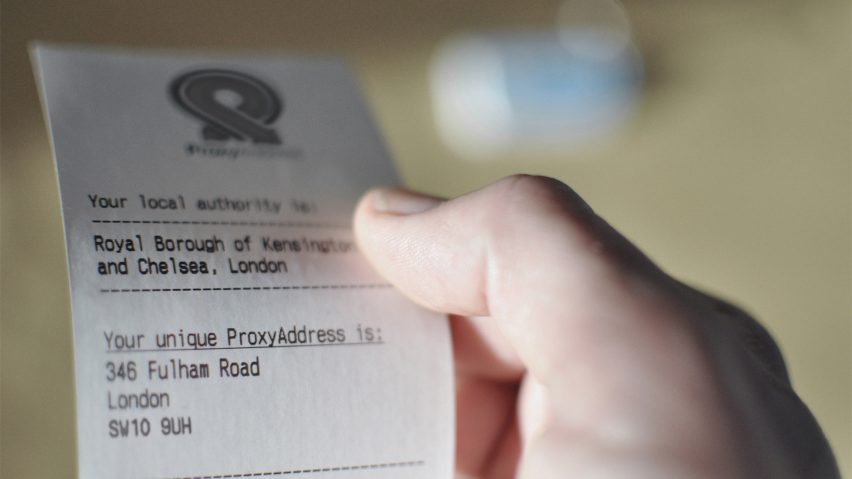

With permission of the property owner, ProxyAddress creates a digital duplicate of a real address.

Often these are empty homes, but can also be council-owned properties, housing association homes or homes still under construction, as well as addresses "donated" by individual homeowners.

The addresses must be real and appear on national address databases in order to be useful. There are no implications for the owner of the physical address like an impact on post or credit ratings, according to ProxyAddress.

Via local authorities, which have responsibility for homelessness services, rough sleepers, sofa surfers or people in temporary accommodation are assigned a ProxyAddress in the area.

These addresses can then be used to make job applications, or to open a bank account with ProxyAddress partners Barclays or Monzo.

Users can update ProxyAddress on where they are staying – such as a friend's house or a homeless shelter – so that mail sent to their ProxyAddress can be redirected to them via postal forwarding.

One user of the Lewisham pilot described the system as "like a VPN in the real world", Hildrey said.

"Move slowly and fix things"

Partners on the pilot included national homelessness charity Crisis, domestic abuse charity Refuge and The Big Issue.

Of the 49 people involved in that trial, which was largely designed to test the banking element and the risk of fraud, 47 were no longer homeless after six months and the remaining two had made "massive progress" according to Hildrey.

Case studies include a man who had been staying in a shelter for two years and is now a regional sales manager for an electronics company living in a north-west London flat. Another was a woman helped to flee domestic violence by ProxyAddress.

The innovation has won several accolades, including the Royal Institute of British Architects' President's Medal for Research and being named one of Time magazine's best inventions of 2021.

ProxyAddress is now gradually working towards a goal of national availability, and is seeking to test that the system can work at scale with the five upcoming roll-outs.

Contrasting the approach with Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg's famous mantra, "move fast and break things", Hildrey said ProxyAddress wants to "move slowly and fix things".

He is hoping the enterprise will one day secure central government backing, with funding still "a constant challenge".

As well as helping to make a positive difference to society, Hildrey claims that by applying their skills more widely architects can help to improve the profession itself.

"Architecture as a profession is struggling and will continue to struggle," he said. "Diversification is what industries tend to do when they start to struggle."

"If you can broaden how we practice architecture, with skills that we're already getting taught anyway, and that can help not only our own fee levels but also help people who are most in need of our services, then I think everyone's a winner, basically."

The photography is courtesy of ProxyAddress.