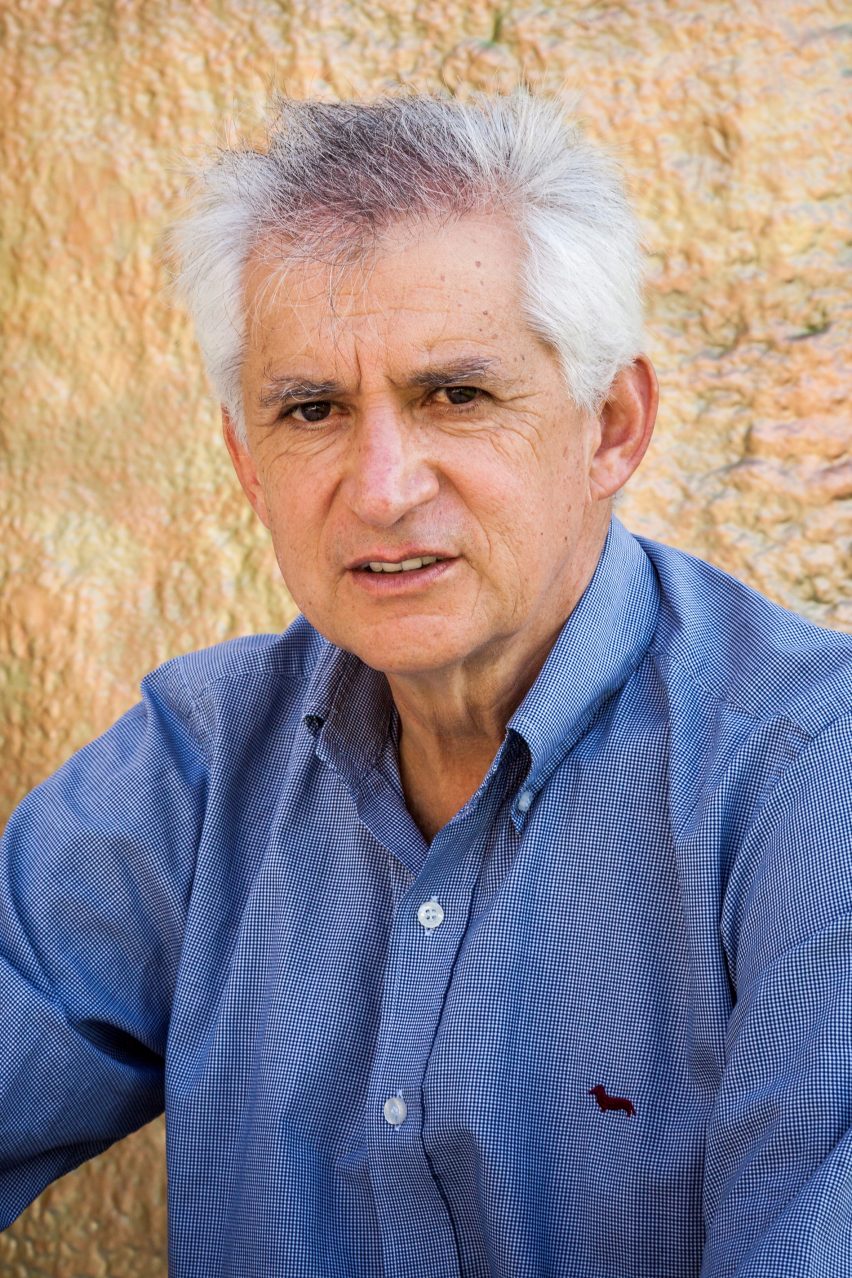

"Every work is very different" in organic architecture says Javier Senosiain

Organic architecture is less a style or school and more a set of principles, Mexican architect Javier Senosiain and Noguchi Museum curator Dakin Hart tell Dezeen in this interview.

Senosiain calls his work organic architecture – a term first coined by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright – but said that the term is mainly a description for architecture that tends away from conventional building shapes and towards natural formations.

"When we see brutalist architecture, or architecture of any certain style, like international, or rationalist architecture, they have a style in common, right?" said Senosiain.

"Perhaps one of the main characteristics of organic architecture is that every work is very different from another, be it from country to country or region to region."

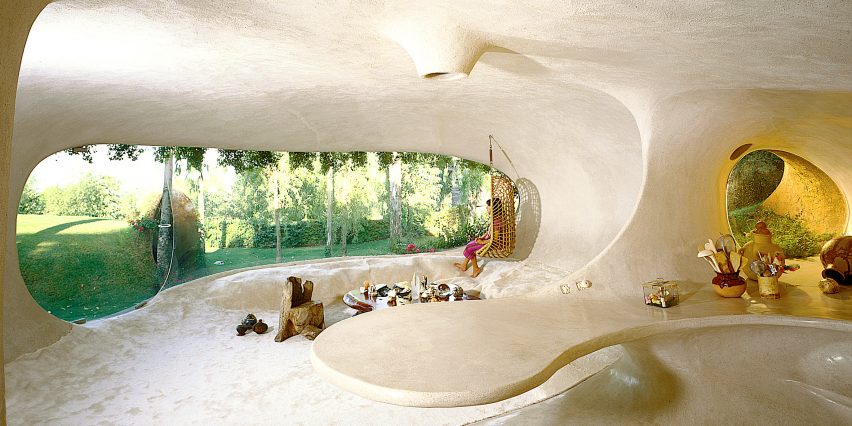

"Organic architecture is the philosophy of architecture that seeks to create harmony between human beings and the natural world," he continued.

Since October, Senosiain's designs have been on show at an exhibition called In Praise of Caves at the Noguchi Museum in New York. The show features a selection of Mexican organic architecture, including Senosiain's work as well as architects Mathias Goeritz, Juan O'Gorman and Carlos Lazo.

"I don't think Javier would, and nor would Noguchi, like the idea of mimicking nature, because we're not talking like old-fashioned mimesis," said Dakin Hart, senior curator at the Noguchi Museum.

"What we're talking about is trying to model after nature. Following nature's footsteps," he added. "You know, evolution is the greatest inventive process in the history of our planet."

Senosiain has been known in Mexico as a practitioner of organic architecture since he completed Casa Orgánica, a shell-shaped house, in the 1980s. Hart describes him as the philosophy's "spiritual mastermind".

Senosiain believes that a current renewed interest in organic architecture runs in tandem with the contemporary acceptance of vernacular architecture and the search for more sustainable materials.

According to Senosiain and Hart, organic architecture is not so much about copying nature but trying to model the built environment after the way that natural systems produce and reproduce themselves.

Senosiain is perhaps best-known for his structures that take fantastical shapes – like his Nido de Quetzalcóatl, a snake-shaped apartment complex – but he said that the adornments and colourations come later in the design process.

"It's a little like when one watches the clouds. One imagines some animal or some vegetable," said the architect.

"For most of our works, when they're in an advanced stage of progress, in organic forms, people start to discern the shape of an animal or a vegetable."

"In the case of designing the Nido de Quetzalcóatl, we had a mockup done with all the curves of level, with all the trees, [something like a] children's pool ring was set up, and it moved according to the orientation and the views, and one day I thought, what if we add the head of a snake at the mouth of a cave?"

Similarly, he told Dezeen that The Shark developed its arresting moniker after earning a nickname among the construction workers on the project.

"In the shark design that we did, when the first stage of the work was done, the masons started calling it The Shark, and then I thought of the fin, and I added a fin," Senosiain recalled.

"I think that over 90 per cent of works that have a name at all, it was not thought about first, but given a name once finished."

Read on for the full, edited interview.

Ben Dreith: In your words, what is the school of organic architecture?

Javier Senosiain: It's a little hard sometimes to classify it because it can have more than one style, right? It can have a style and then another style and it may have variations but somewhere, there is a definition that says that organic architecture is the philosophy of architecture that seeks to create harmony between human beings and the natural world.

Dakin Hart: It's more principle. Though Javier is the spiritual mastermind, the intellectual force behind this, it is not a movement, per se. It encompasses all of human building history. And this is just a more recent chapter that we're tapping into, but the shape that it has, the coherence that it has, as a group of ideas that you can really work with, has come from Javier.

BD: An idea of organic architecture mimicking principles of nature seems in contrast to the artifice of a gallery. Why show these works at the Noguchi Museum?

DH: I don't think Javier would, and nor would Noguchi, like the idea of mimicking nature, because we're not talking like old-fashioned mimesis, you know, this is not art holding up a mirror. What we're talking about is trying to model after nature. Following nature's footsteps. Noguchi didn't see technology and nature as opposing forces. He thought of nature as the greatest technologist. So it's a matter of a different theory, a different set of principles and processes in the development of new ideas, which nature is coming up with all the time. You know, evolution is the greatest inventive process in the history of our planet.

BD: What are some everyday examples of organic architecture that people can latch on to?

DH: The mass of architecture more generally is cognizant of at least the symptoms of all of the problems that have been caused by not building it all organically. It's trying to look at where we've been, and looking back to times when maybe we were building more simply but also more rationally, in ways that it turns out were also more efficient because they were more closely connected to natural models. But I think there's no question that there, again, those latent tendencies are already always there and they're just coming out again, they're coming to the forefront. And now they're being understood as a solution to our problems and problems that we've created for ourselves.

JS: Yes, yes, organic architecture is, on one side, very wide. I think there is a lot of influence from vernacular architecture, in fact, in 1964, Bernard Rodowski's exhibition of architecture without architects, I think with that, somehow, there was a change in the world, and I remember, in the architecture career at college, you did not see vernacular architecture. And it was like a novelty, or more diffusion for that kind of architecture, which was not well-known in the world, and I think that modern organic architecture goes back to the origins of vernacular architecture a lot. And I think that's why Dakin was saying that a large part of modern architecture is using a lot of natural materials – such as wood, stone, earth, etc, and from that vernacular architecture, though there is some likeness in some latitudes, at the same time organic architecture has a special quality that I see.

BD: Why has Mexico been such an important place for the continued development of these ideas?

JS: [Architect] Mathias Goertiz said that he could not have done what he did in any other country and I think it's a place that has a lot of advantages because of cheap labour, a country well known for its plastic arts, you know? And I think all of that helped.

I don't know whether to call organic architecture a style or a school, but it has something not so common or conventional, in the sense that every work is generally very different. When we see brutalist architecture, or architecture of any certain style, like international, or rationalist architecture, they have a style in common, right? Like Barragan and such. Perhaps one of the main characteristics of organic architecture is that every work is very different from another, be it from country to country or region to region. Right now Yolanda Bravo Saldaña is making a book of organic architecture in general, and all the pictures she is compiling, well, they're all so different. Perhaps in the Mediterranean, for a while in the '60s, with ferrocement, they were slightly similar things being made, the constructive system, etc, but every work is very different, isn't it? That's one of the main characteristics I see in organic architecture.

BD: Why has your implementation of the principles led you to use these very symbolic shapes or literal animal forms and natural forms?

JS: That symbology is not born a priori, but a posteriori. It's a little like when one watches the clouds. One imagines some animal or some vegetable. For most of our works, when they're in an advanced stage of progress, in organic forms, people starts to discern the shape of an animal or a vegetable. In architecture that's, not conventional but more traditional, for example in Mexico, there is a building called El Pantalón ("The Pants"), and I am sure the architect did not think of a pair of pants. Still, people started seeing it and thinking of pants.

I know that they didn't think of it a priori, but that people later started calling the buildings that. In the shark design that we did, when the first stage of the work was done, the boys/the masons started calling it The Shark, and then I thought of the fin, and I added a fin. I think that over 90 per cent of works that have a name at all, it was not thought about first, but given a name once finished.

In the case of designing the Nido de Quetzalcóatl, we had a mockup done with all the curves of level, with all the trees, [something like a] children's pool ring was set up, and it moved according to the orientation and the views, and one day I thought, what if we add the head of a snake at the mouth of a cave?

BD: So it's like the storytelling or narrative of the design dictates how the work is view and where it is going. Does this aspect of storytelling and narrative in the design help point to where the practice is going?

DH: I like that idea very much. That this is extending and it's more connective. That's so fundamental. It's very vague, but it's extremely important. That organic architecture one of its main principles is just more connection. Because architecture in the 20th century is all about separation. Javier is thinking about making buildings is trying to link much more into daily activity in a way that's more innate to what we are, and recognizing that we are not trying to separate us from what we are.

JS: Yes, yes, there was a master of mine who spoke of the importance of the whole, of the importance of integrating the parts with the whole and the whole with the parts, I think that integration and continuity are important, it's like space, it flows, and you have to let space flow. I really like a work that I often analyze with my students too, the Guggenheim in New York, which I think is characterized as a sculpture, but where space flows, space is continuous, and the function is continuous - you go up the elevator and it is continuous. The structure is continuous. The shape is also continuous. I think the Guggenheim is a great example of continuity and integration – with little elements, it's able to resolve all that.

The photography is courtesy of Javier Senosiain, unless otherwise stated.