"I don't end up with beautiful objects right away" says Jorge Penadés

Spanish designer Jorge Penadés draws on unlikely sources for inspiration, from toilet-roll tubes to shelving strips. In this interview, he explains why cares more about how things are put together than how they look.

Madrid-based Penadés, 38, works across furniture, lighting, interiors and accessories.

His work is underpinned by a fascination with the construction systems behind design objects, which he considers more important than the finished aesthetic.

"I don't end up with beautiful objects right away," he told Dezeen.

"I prefer to put more energy and time into thinking about the further possibilities of what we are creating, rather than the outcome of what we're going to sell right away," he said.

This doesn't mean that Penadés creates unattractive designs, but it does mean his projects often incorporate innovative production methods or make clever use of simple materials.

Obsessed with joints

His latest project, which featured in the Natural Connections exhibition at Madrid Design Festival, creates a bench, shelving unit and table with the same industrial process used for the manufacture of toilet-roll tubes.

Instead of cardboard, the Wrap furniture is formed of hollow tubes of cherry wood veneer. These are linked by solid wood ball joints, resulting in a framework that is extremely lightweight and inherently versatile.

Another project saw him build a series of quick-assembly pavilions and furniture pieces out of nothing but plywood boards and kinesiology tape. The latest iteration– titled Tape! Tape! Tape! – was shown at the Alcova exhibition in Milan last year.

Penadés said he is "particularly obsessed with construction systems and joints".

He believes that, rather than focusing on single objects, it's more useful to design an assembly system than can be used in endless configurations so the idea can take on a life of its own.

"I find it interesting to make a structure that allows someone else to create whatever they want. You create whatever and it's not up to me," he said.

"It takes a little bit longer to design a smart construction system, but once you get to this point the possibilities are endless," he continued.

"That's why I like joints. I like to design things that offer more possibilities than just a lamp or a bench."

Using "what already exists"

The designer has also applied this thinking to materials.

Structural Skin, a project that Penadés first developed in 2015 for his masters degree at IED Madrid, involved creating a new material out of waste leather.

By shredding leather offcuts and combining them with bone glue – a natural binding agent that, like leather, is a byproduct of the meat industry – Penadés created a solid material that could be shaped like wood.

When cut or shaved, the material reveals colourful patterns reiminscent of marble or wood grain.

This project led many to think that recycling was the driving force behind Penadés' material choices. In fact, he is broadly interested in any material that is readily available at volume.

His projects are just as likely to incorporate off-the-shelf materials and components.

"A lot of people see me as having a recycling mindset, and in some ways I do," he said. "But it's more accurate to say that I'm interested in finding new possibilities in what already exists out there."

A new approach for Camper

Penadés is selective when it comes to brand collaborations. He finds that, while manufacturers are interested in his appraoch, it doesn't easily translate into their way of producing products.

"The conversation always ends the same: 'Jorge, we really like your thinking but we don't know what to make with it'," he revealed.

However one brand has embraced it. After creating a store for footwear brand Camper, the Mallorca-based company asked him to oversee its interior design going forward.

In the past, Camper stores have been designed by international stars like Kengo Kuma and Jaime Hayón, with bombastic interiors that include entire walls of shoes and ceilings mades out of laces.

On discovering that Camper can often spend a year "fixing things that didn't work" after a new store installation, Penadés decided to take an approach that instead prioritised functionality.

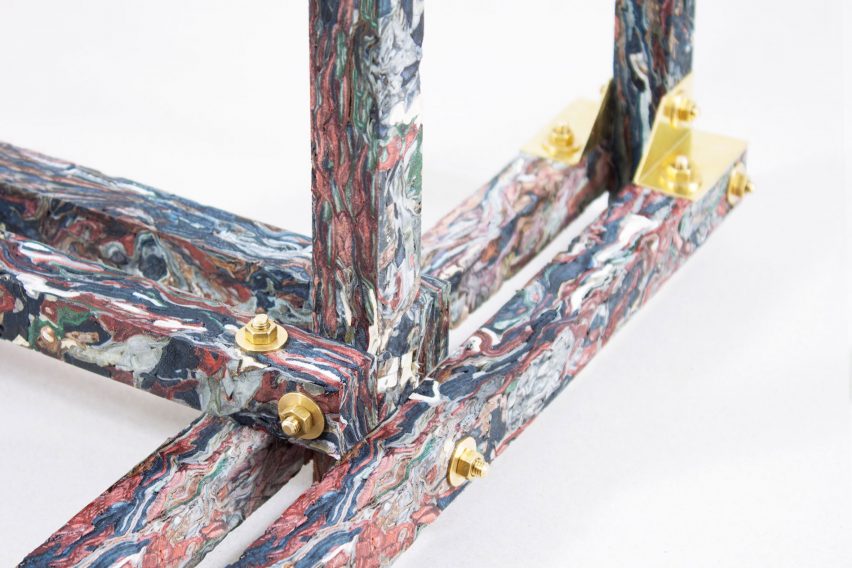

His first store, in the Spanish city of Málaga, was constructed entirely from ubiqitous metal profiles, held together by corner plates, and nuts and bolts. Crucially, he and his team built the entire thing themselves in Camper's factory.

Despite its modest contruction, the design is highly distinctive and characterful.

"I realised what I could do was make a shop that would actually work," Penadés said. "I didn't invent anything. I just used what was available and twisted it to create a new language."

"My goal was to go beyond the conventional way of doing things, using something that exists already," he said. "I think this really summarises my approach. It's about creating a new way of constructing that delivers something unexpected."

Read on for an edited transcript of the interview:

Amy Frearson: Can you explain the Wrap project and the idea behind it?

Jorge Penadés: My main interest is in how you can, with very little, do as much as possible. I'm particularly obsessed with construction systems and joints.

When AHEC invited me to this project, I had already semi-developed an idea to translate the production process behind the cardboard tubes you find in rolls of kitchen paper and toilet paper. I was interested in how, with two sheets of very thin material, you can create a structure. I decided to translate this production process into wood veneer.

We developed a process for glueing 0.7-millimetre-thick sheets of wood veneer against each other in opposite directions to create a pipe. Together with solid wooden joints, we created a construction system. The result is a two-level seat, a long shelving unit and a table.

Amy Frearson: Do you see greater potential for this system? What possibilities does it offer?

Jorge Penadés: There is great potential. It's amazing that, with a 0.7-millimetre-thick material, you can make a structure that is strong but also light. I can lift that five-metre-long shelf all by myself.

Waste is something that we all have in mind nowadays. The binder for these tubes is just a very thin layer of glue, so there is not much energy, time or resources needed. It makes sense to push it further. Now, it's a matter of finding a company that is keen to develop products. Because the challenge is to go from these one-off pieces to start developing a more efficient, industrial production process for these pipes.

Amy Frearson: What first led you to think about translating toilet roll tubes into furniture?

Jorge Penadés: Around 2015 or 2016, I became fed up of being called the leather guy.

For my masters graduation project, I had developed a new material called Structural Skin out of leather offcuts. I would shred these leather leftovers in a paper-shredding machine and mix them with bone glue, which is basically collagen. Both components are byproducts from the food industry. This created a new material.

I started trying to find more solutions for using leather in a structural way. At the time I was talking to Pascale Mussard of Petit H, a startup within Hermès, who was comissioning artists and designers to work with Hermès' offcuts. She was interested in doing something together, so I started this study.

We developed this leg, made by rolling leather and glueing it together. Because it was so inefficient, and because we were wasting so much leather, we decided to do a test with a cardboard kitchen roll inside. This was where the magic happened. I became more interested in what was happening inside than in the finished product. That led me to start to investigating this cardboard production world.

Amy Frearson: Do you think it would be possible to create a version in leather?

Jorge Penadés: I have already developed it. I'm really drawn to leather so, whenever I have a new idea, I often model in leather. It's a material I find very easy to work with.

My first thought was how to translate the cardboard tube into leather, because cardboard has a low-cost perception and I wanted to elevate it. I like to decontextualize a material or a production process, to mix up things that don't have an obvious relationship to each other.

That's also why, when I got the AHEC commission, it was obvious to me to work with wood veneer rather than solid wood. I'm always trying to find that lateral angle, to try to do something that has not been done before.

Amy Frearson: Beyond cardboard tubes, mass-produced and off-the-shelf components appear to be a regular feature in your work. What attracts you to these elements?

Jorge Penadés: I'm interested in structures and particularly in joints, which are the key elements of a structure. It's something about versatility and flexibility. I find it interesting to make a structure that allows someone else to create whatever they want. You create whatever and it's not up to me.

It takes a little bit longer to design a smart construction system, but once you get to this point the possibilities are endless. That's why I like joints. I like to design things that offer more possibilities than just a lamp or a bench.

Amy Frearson: It's quite unusual for a designer to be more interested in the production process than the end product. Does this cause issues when you're working with brands/manufacturers?

Jorge Penadés: It's funny you ask this. I have had many conversations with manufacturers and – apart from BD Barcelona, who I worked with on a collection of vases – none of them have really understood what my work is about. The conversation always ends the same: "Jorge, we really like your thinking but we don't know what to make with it."

The problem is that I don't end up with beautiful objects right away. I prefer to put more energy and time into thinking about the further possibilities of what we are creating, rather than the outcome of what we're going to sell right away. That's just the way I work and the way I like to work. I prefer to wait until someone trusts this way of working.

Amy Frearson: Can you give me an example of a project where you have been able to apply this approach?

Jorge Penadés: The Tape project is a good example. I was invited to Concéntrico, an architectural festival in Spain. The brief was 20 plywood boards and €2,000 for production. I came up with this concept to built structures using only these boards and kinesiology tape [a flexible tape typically used for athletic injuries]. I said I wanted to translate a knowledge of kinesiology tape to architecture, on the basis that bones and muscles are all also structures. But really I was thinking about how I could create a very temporary solution. The festival is only one week and at the end, I wanted to be able to resuse the wood. So we ended making a pavilion using just plywood and tape. We built it in three hours.

After that, Jane Withers invited me to bring the idea to the Brompton Design District in London. I didn't want to make the same joke twice, because it's not funny any more, so I told her I wanted to further explore it. I said I wanted to do three pavilions in three different locations, each built and disassembled on the same day. We did the first in front of the V&A. The second was outside South Kensington station. The third was supposed to be on Exhibition Road, but because it was raining we were sent inside the underpass. It meant we had to come up with a new solution in 30 minutes.

My original proposal for the last day had been to cut all the boards and turn them into furniture for people. I still had this idea in mind when Joseph Grima and Valentina Ciuffi approached me to do something for Alcova at last year's Milan design week. So I spent one week making furniture live.

This all shows how fast and intuitive you can be with this construction system that is just plywood boards and tape.

Amy Frearson: Are you able to apply the same kind of thinking to the retail projects you are working on with Camper?

Jorge Penadés: I think that's how I ended up getting involved with Camper. As I said, my design approach is about doing the maximum with very little resources, which I think is a very Mediterranean type of thinking. Countries in the south of Europe have not been the wealthiest; if you don't have a lot of resources, you have to make the most out of them.

Camper is very linked to the Mediterranean, as it based in Mallorca, and was looking to switch mindsets. They had pioneered the Camper Together format back in the early 2000s, linking their brand with particular designers, architects and artists. That formula has since been widely replicated and no longer feels pioneering, so they wanted to go back to their Mediterranean roots to find a new strategy.

I think that's why they invited me to do a few shops for them and why they ended up asking me to take on this role as Camper studio director.

Amy Frearson: Can you explain how you approach a Camper store interior, and how that differs from the high-profile architects and designers they have worked with in the past?

Jorge Penadés: A good example is the Málaga store, the first one I did. Camper has a huge warehouse full of unique pieces, almost museum pieces, from Gaetano Pesce, Ingo Maurer, the Bourellec brothers, Jamie Hayon, you name it. There are pavilions by Kengo Kuma and Shigeru Ban.

They wanted me to take pieces from all these designers and make a shop out of them. When I saw this huge warehouse, I thought: "Who am I to touch these pieces?" I didn't want to do a Frankenstein.

Camper told me that, usually when they do a new shop, the architect or designer would plan a scheme then hand it over to a constructor to build. Once the shop was open, Camper would then typically spend a year fixing things that didn't work. Here I was, three years out of school and I had never designed a shop in my life. I realised what I could do was make a shop that would actually work.

I told them: "I'm not going to follow your brief. Instead, I'm going to build a shop for you myself. That's the only way I can make sure it will work. I'm going to bring my team to Majorca and we're going to prototype a full-size shop here. You're going to complain, because for sure I will do something wrong. But I'm going to solve it for you. Once we've agreed that it works, we'll send it to the location to be installed."

Amy Frearson: How did that play out?

Jorge Penadés: They liked my attitude and I think they saw the potential in the idea.

We did it with only three main elements: a perforated metal profile that you can find in any hardware store, triangular metal corner plates from the same system, and nuts and bolts. I didn't invent anything. I just used what was available and twisted it to create a new language. We had a lot of fun doing that. We created every single element of the shop: the counter, the seating, the shelving. We created hinged doors with magnets, so they could have storage under the tables. We also developed a typography with these triangles.

My goal was to go beyond the conventional way of doing things, using something that exists already. I think this really summarises my approach. It's about creating a new way of constructing that delivers something unexpected.

Amy Frearson: It seems to me that, at a time of concerns about sustainability and resources, many designers are trying to shift to a materials-first approach. But what you're saying is that this approach is actually what comes naturally to you?

Jorge Penadés: Yes exactly. A lot of people see me as having a recycling mindset, and in some ways I do. But it's more accurate to say that I'm interested in finding new possibilities in what already exists out there. In this example of the Camper shop, it was an off-the-shelf shelving system. The shop has my name on it, but really it should have the name of the designer behind this. It's the smartest structure that I can think of. You can do anything with it.