Market forces are pushing cities towards a shallow and Instagram-friendly impression of authenticity that makes everywhere feel the same, writes David A Banks.

If you've started traveling again since the pandemic, you may have noticed something unsettling. Maybe you detected it before the lockdown too. Everywhere looks the same, even as each city proclaims louder than ever that they are unique and different.

Cities and neighborhoods are branding themselves into predictably unique products. Nothing too daring, just a hint of local flare – a microbrew IPA named after a local landmark, a "general store" that sells tchotchkes with a stylized drawing of the downtown skyline.

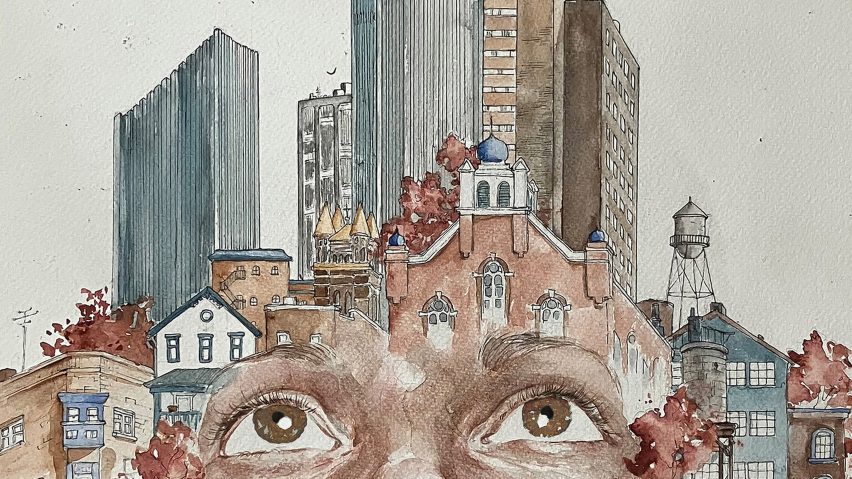

The city is increasingly thought of as prop and backdrop for a life lived on Instagram

These are just a few of the elements of the city authentic, the third and latest movement of urban development. And just like the city beautiful and city efficient movements that preceded it, the city authentic will leave a lasting impact on the urban landscape.

The city authentic is the name I give to the convergence of ascendant marketing and economic development techniques that leverage the popularity of urban life to trigger reinvestment in long-neglected cities and towns. Whereas the city beautiful used steam and steel to build awe-inspiring theaters and museums, and the city efficient harnessed the power of computer and zoning codes to plan out highways and subdivisions, the city authentic uses social media and smartphones to revitalize downtowns and attract new investment.

The city authentic is global but it is largely endemic to small and medium-sized post-industrial cities in rich nations. Edinburgh's Stockbridge neighborhood, replete with trendy bars and hip thrift stores, is a good example. Small towns in Italy have taken it a step further and turned into albergo diffuso – distributed hotels with amenities scattered throughout the settlement. And near me, in Upstate New York, cities that used to specialize in textiles and heavy manufacturing are busy luring restaurants, bars, and concert venues to help entertain the video game developers and biotech engineers working nearby.

In each case, history and geography are packaged and sold as something to be tenuously experienced and consumed through your phone. From the interior decoration to the public art, the city is increasingly thought of as prop and backdrop for a life lived on Instagram.

Why this particular kind of development? What is it about exposed bricks and beams, bespoke amenities, and a focus on local history that gets the grant money flowing and the 20-somethings visiting?

The answers to these questions lie at the confluence of 21st-century cultural trends and post-industrial political economy: a contradiction of the market where companies are least prepared to offer seemingly authentic experiences precisely because of how they generate that desire.

Meanwhile the places where new culture is made and tested are disappearing

Algorithmic advertising and just-in-time supply chains have rendered our material culture into a postmodern pastiche of recycled symbols and styles of earlier decades. This was detectable as early as 2011, when Kurt Anderson wrote in Vanity Fair: "The past is a foreign country, but the recent past – the '00s, the '90s, even a lot of the '80s – looks almost identical to the present."

This happens to architecture too. As ever-rising land prices ate into development budgets, architects and engineers reached for a universally available kit of parts to clad their five-over-ones. Regional vernacular architecture may be intentionally deployed in some high-end developments, but default construction material is drawn from an international market of engineered parts that only need minor tailoring to the site's particularities.

Meanwhile the places where new culture is made and tested are disappearing. Typically, the most daring, inventive art and culture comes from the margins where cheap rent in urban environments allows for experimentation and cross-pollination.

But now that the interests of finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) industries have supplanted manufacturing in nearly every major city, rents are climbing ever upward. That not only means more Americans are rent burdened than ever before, but even the well-off and upwardly mobile find that a comfortable life in the city is always out of reach.

The city authentic may preserve cities' most cherished pieces of architecture. I have been relieved to see beautiful Victorians and stately brownstones saved from the wrecking ball and renovated into gorgeous, useful buildings. But what goes on inside them is inaccessible to all but the highest earning, newest residents of my city.

That hardly seems fair, and it certainly isn't a sustainable way to build an economy. Replacing the FIRE industries with a more egalitarian, unionized economy should be recognized as a promising path to developing better cities.

What sets us apart will be commodified until there's nothing left

As for the built environment, this is a global issue that resists sudden changes despite the looming threat of climate catastrophe. It is often said that the most sustainable building is the one that's already built, and so reforms to financing that incentivize and help pay for reuse and renovation over greenfield construction would be welcome. Otherwise, only the richest firms and families will be left to steward our architectural legacy. And once they're renovated, they need to stay affordable, and so rent controls and public ownership of land have to be on the table.

But what to do about new construction? How can we build places that feel meaningful again? The architecture critic Kate Wagner has argued persuasively on two fronts: first that unionizing architectural firms could change what gets built and under what conditions. By giving a broader swath of the architectural profession a collective voice, there's a chance that the worst excesses of starchitecture can be abated and a more humble and humanistic ethic can emerge.

Second, as we demand a better built environment we must be careful not to slip into aesthetic moralism. That is, we must not give credence to "the belief that one aesthetic is inherently better or more righteous than another". Because the incentives in real-estate development are so skewed, some of the most socially responsible projects have the least funding and so we must be forgiving of an uninspired building if what goes on inside is good for society.

Don't get me wrong, I like a lot of the stuff that I can still afford – the Farmers' Market can't be beat, there's a few new music venues that foster a great scene, and I have a new favorite restaurant that makes a killer chopped cheese (check out Naughter's if you're ever in Troy).

But there's nothing stopping what's happened to SoHo or Williamsburg from happening here. Indeed, there is every indication that we're headed toward that same fate. What sets us apart will be commodified until there's nothing left but bank branches and chain stores under luxury condos.

David A Banks is a lecturer in the Geography and Planning department at University at Albany, SUNY and director of the Globalization Studies program. His first book, The City Authentic: How the Attention Economy Builds Urban America, is published by the University of California Press.

The illustration is courtesy of University of California Press.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.