"Not focusing on the building as a system can compromise sustainability goals"

It's time for architecture to take a more holistic approach to reduce the climate footprint of buildings, writes Trimble SketchUp's Hugh McEvoy as part of Dezeen's Climate Salon partnership with the software company.

It has been uplifting this year to witness what was once a somewhat-sceptical sector now vocalising – loud and clear – its concerns over sustainability.

Be it at conferences, panel discussions or networking events, more and more decision-makers in the built environment are holding themselves accountable, at least in part, for climate change.

Considering that 40 per cent of carbon emissions are emitted by constructing and operating buildings and 35 per cent of total waste is created by construction projects globally, their worries are more than reasonable.

Recently, the UIA World Congress of Architects in Copenhagen exhibited how architecture plays a vital role in achieving the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals through the explorative SDG Pavilions.

This collection of 15 experimental projects showcased how architects can take advantage of unconventional materials, technology, and design strategies to build spaces that are kinder to the environment.

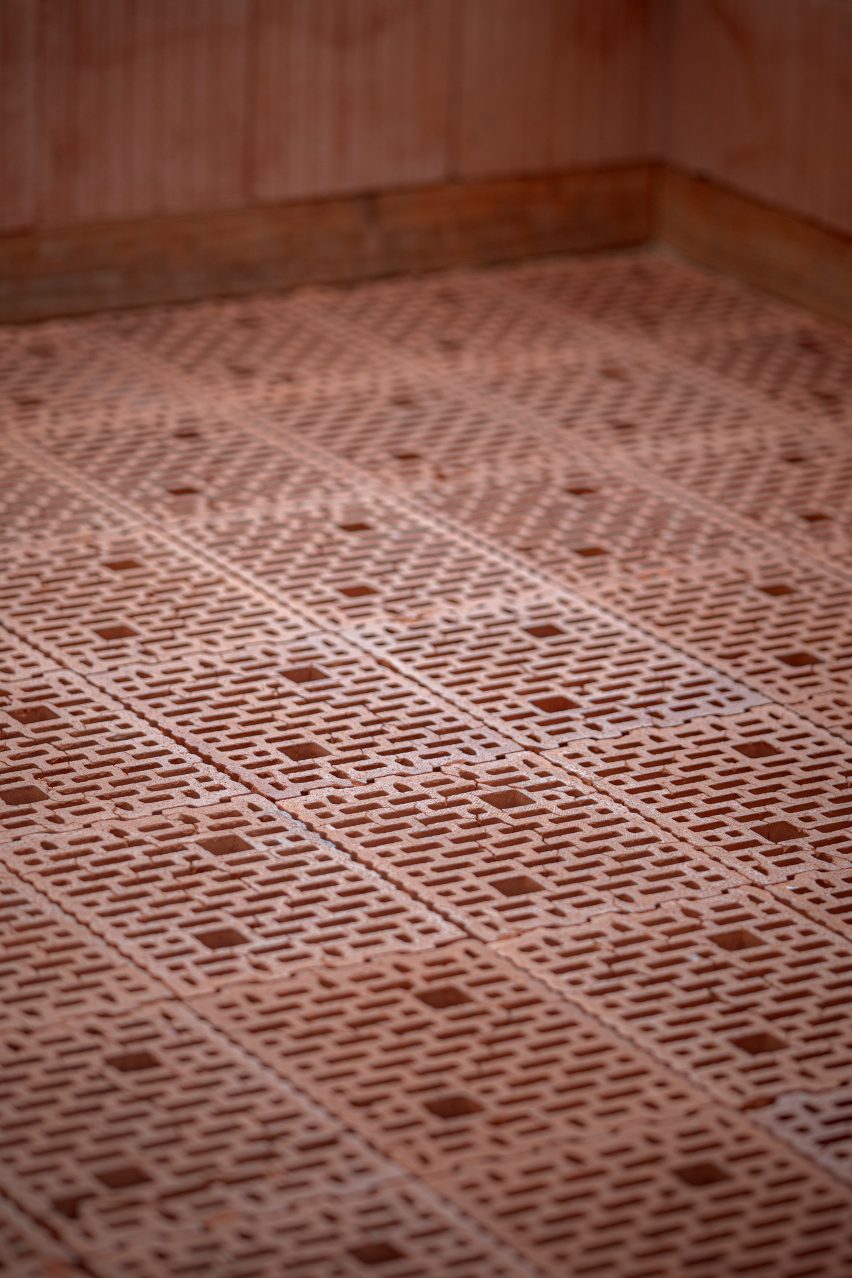

Some of the pavilions focused on a specific element of architectural design – material specification – to tackle the climate emergency. The 4-1 Planet Pavilion, for example, presented alternative solutions to conventional materials for housing, including compressed clay soil and round timber.

In Denmark, this makes a lot of sense: with strict building emissions legislation in place for years already, a much larger proportion of lifetime building emissions are associated with building materials than is the case in most other countries.

In other words: as operational carbon is reduced, material carbon – embodied carbon – becomes a larger proportion of the overall lifecycle carbon.

However, while it may make sense in Denmark to focus primarily on building materials, in the rest of the world paying attention to only a single aspect of the design will not provide the ultimate solution to climate change.

Sustainability in construction boils down to championing a holistic, connected approach to building design. Materials selection plays an important role in reducing construction's environmental impact, of course, but is not enough on its own.

To make the required improvements in sustainability, stakeholders – including architects, contractors and engineers – must collaborate with one another and commit to addressing inefficiencies, rework, and waste throughout the building's entire lifecycle – from design through construction to operations and maintenance.

Take concrete, for instance. Concrete is notorious for having a high embodied carbon footprint, which is why many architects who focus on sustainability shy away from it.

However, the material has high thermal mass: if used in the right quantity, for the right reasons, it can help reduce heating, ventilation and air-conditioning peak loads, which are a major determinant of operational energy use, and therefore carbon emissions.

Calculating the true carbon footprint of materials is somewhat complicated. Bamboo, for example, is, in theory, a sustainable material. However, if it's not grown locally and instead shipped from a country many miles away, the amount of carbon emitted during transportation can reduce the potential CO2 savings from choosing bamboo as a material in the first place.

In other words, in order to achieve truly sustainable design, architects should make design decisions based on the performance of a building in the context of its environment.

Making design decisions in isolation risks ignoring how building elements, such as windows, walls, heating and air-conditioning interact with each other, as well as with the local environment. Ultimately, not focusing on the building as a system can compromise sustainability goals.

We believe that collaboration is key to sustainability in architecture and design. Historically, the operational performance of a building has often been treated as "the engineer's problem".

However, this aspect of sustainability is too important for architects to leave it to a group of professionals who are often only engaged once the conceptual design has been agreed on.

Both parties should work collaboratively right from the start of the project to explore different design strategies and their impact on energy performance. Using early-stage energy analysis software makes operating performance a design input rather than an output.

Fortunately, technology already exists to allow architects and engineers to accurately calculate the interactions between the different building elements. Software such as SketchUp, Sefaira, and PreDesign (part of both the SketchUp Pro and SketchUp Studio subscriptions) enables architects to execute performance analysis in the early stages and explore different design strategies at the speed of design.

This iterative, data-driven approach to design helps the team test and try different ideas quickly, and enables the final design to showcase reduced energy use, lower running costs and lower carbon emissions, as well as being more appealing to a potential buyer or tenant.

The technology exists for architects to begin the crucial transformation now. In the end, innovation will come from pushing the sector further, instead of remaining stuck in traditional ways of working.

Hugh McEvoy is the director of strategy and sustainability lead at Trimble SketchUp.

Partnership content

This article is part of Dezeen's Climate Salon partnership with SketchUp. Find out more about Dezeen partnership content here.