Architects need to rethink their part in Britain's dysfunctional relationship with laundry, writes Phineas Harper.

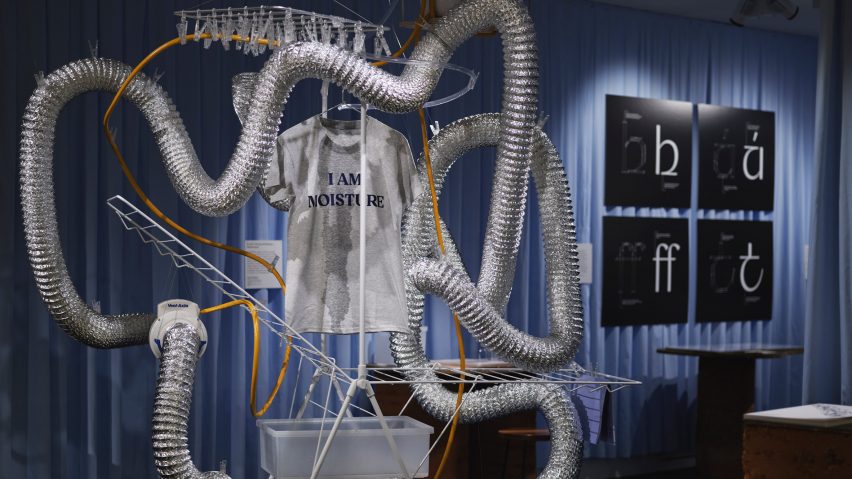

A tangle of tubes, ducts, and electrical appliances hanging in moist air around a sodden cotton T-shirt is the undisputed highlight of Islands, a new exhibition at the Design Museum. Created by design researcher-in-residence Marianna Janowicz and feminist architecture collective Edit, the exhibit is a monstrous metaphor lampooning Britain's dysfunctional relationship with laundry.

A heater and fan cause water to evaporate from the soggy T-shirt, whereupon a dehumidifier condenses the vapour to liquid again and dribbles it back onto the garment. Titled D.A.M.P. (Drying and Moisture Performance), the piece mocks the highly mechanised and often conflicting processes that Brits are resorting to in order to dry their clothes as drying laundry outside on washing lines becomes increasingly policed.

Edit has been interrogating the architecture of domestic labour including laundry since their 2018 inception. In 2021 they hung pants, shirts and socks on a washing line in front of the RIBA as a provocation challenging conservative attitudes to laundry drying in public. Now Janowicz has taken the design collective's research further – probing the architectural history of laundry in the UK and how it has become shaped by growing anti-working class sentiment.

Britain is increasingly hostile to anyone drying their laundry outside

Across the world, clothes have traditionally been laundered in public. In Europe lavoirs, communal wash houses where garments could be brought for cleaning, were once a common feature of the urban landscape. George-Eugène Haussmann's 1850 redesign of Paris, for example, included lavoirs in every neighbourhood.

Though mechanisation has automated much of the drudgery of hand washing clothes in rich countries, shared laundry facilities are still widespread. "In Switzerland, Sweden and other European countries it is commonplace to have communal laundry rooms in housing blocks," says Janowicz, "while in Venice, you see many shared washing lines spanning canals and campos". Britain, on the other hand, is increasingly hostile to anyone drying their laundry outside.

"No washing on balconies. This is not a council estate" declared an anonymous all caps note that went viral in 2019 after the recipient posted it on Mumsnet. The unpleasant message, taped by a neighbour to the front door of a mother who'd been drying her family's clothes on the balcony of their flat, is emblematic of a growing judgmental attitude to laundry that has become a feature of modern Britain.

During the pandemic, social landlord L&Q wrote to residents of Chobham Manor in Newham designed by Make Architects demanding they stop drying laundry on their balconies. The company, which was recently found by the housing ombudsman to suffer from "severe maladministration" and an "overtly dismissive" attitude to its tenants, said that wet clothes posed "a fire risk" and were "an eye sore".

Until relatively recently, UK attitudes were very different with clothes drying outside a common sight

Contradicting the housing association's own damp-prevention guidance, which advises "drying washing outdoors", the condescending and typo-riddled letter revealed its authors were more concerned with protecting "image of the development" than the practical needs of its residents. Janowicz has uncovered scores of further examples of local authorities and housing management companies both banning laundry on balconies and reprimanding tenants for exacerbating mould issues by drying their moist clothes inside.

Yet until relatively recently, UK attitudes were very different with clothes drying outside a common sight in cities, and many of the best British housing estates designed with expressive laundry facilities. For example, the 1938 Sidney Street Estate in Somers Town was built with courtyards featuring washing line posts topped with colourful sculptures by ceramicist Gilbert Bayes.

Elsewhere, Berthold Lubetkin and Tecton's Spa Green Estate, completed for the former Metropolitan Borough of Islington in 1943, included a rooftop laundry terrace with an aerodynamic canopy designed to enhance the evaporative effect of breezes. Ernö Goldfinger created drying rooms in the core of Balfron Tower. Even the tiny 1964 Vanbrugh Park Estate where I live, designed by Geoffrey Powell of Chamberlin Powell and Bon, included a small laundrette and distinctive drying area cupped by curving brick walls.

But in 1976 London's municipal government, the Greater London Council (GLC) closed approximately 1,000 laundry and drying rooms overnight. Harry Kay, vice chair of the GLC Housing Management Committee, promised the closures were a temporary safety measure following a freak accident that had seriously injured a young girl, but with local government finances under pressure, the facilities never reopened. Vanbrugh Park's laundrette became a store room; Balfon's drying room is now a unused yoga studio; Spa Green's roof terrace has been closed for five decades; and Sidney Street's ceramic finials were stolen.

Britain's architects should refuse to allow this moralising snobbery to continue define their approach to designing for domestic care

With the sudden removal of communal facilities, positive attitudes to drying laundry in public quickly deteriorated. Rising 1980s consumerism under Margaret Thatcher's government saw owning personal appliances like washing machines and tumble dryers become status symbols while using a laundrette, like riding a bus, was seen by many as a mark of poverty and shame.

For Edit, however, it is absurd that once traditionally male forms of labour like office work, manufacturing and governance are celebrated with substantial facilities in city centres, while domestic labour like laundry is relegated to the home and hidden from public view. "Care work like laundry makes up the majority of work that we do in the world," points out Janowicz. "We should be taking the architecture of care very seriously. I want to see a policy for restoring community laundry infrastructure. Communal facilities can save space and resources, freeing up the home for other things."

Hanging laundry outside is not only easy, cheap and helps prevent damp problems, it's patently more environmentally friendly than energy-inefficient mechanical drying. Knowing this, some contemporary architects are devising new laundry facilities for the communities their work serves. La Borda by Lacol in Barcelona and Nightingale 1 by Breathe in Brunswick, Australia, for example, are co-housing schemes that feature generous multi-purpose areas which provide space for laundry alongside other communal uses.

Failing to build decent outdoor laundry areas in new housing estates or, worse, imposing mean-spirited rules banning drying clothes on balconies, are an unsustainable, prejudiced and myopic hangover from Thatcher-era prejudice. Britain's architects should refuse to allow this moralising snobbery to continue to define their approach to designing for domestic care, and instead learn from Lubetkin and Powell, harnessing solar and wind energy to design inventive and generous laundry faculties for all.

The photo of D.A.M.P. (Drying and Moisture Performance) is by Felix Speller.

Phineas Harper is chief executive of Open City. They were previously chief curator of the 2019 Olso Architecture Triennale, deputy director of the Architecture Foundation and deputy editor of the Architectural Review. In 2017 they co-founded New Architecture Writers a programme for aspiring design critics from under-represented backgrounds.

Island is on show at the Design Museum until 24 September 2023. For more exhibitions, events and talk in architecture and design, visit Dezeen Events Guide.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.