Customisable 3D-printed handles take pain out of toothbrushing for people with limited dexterity

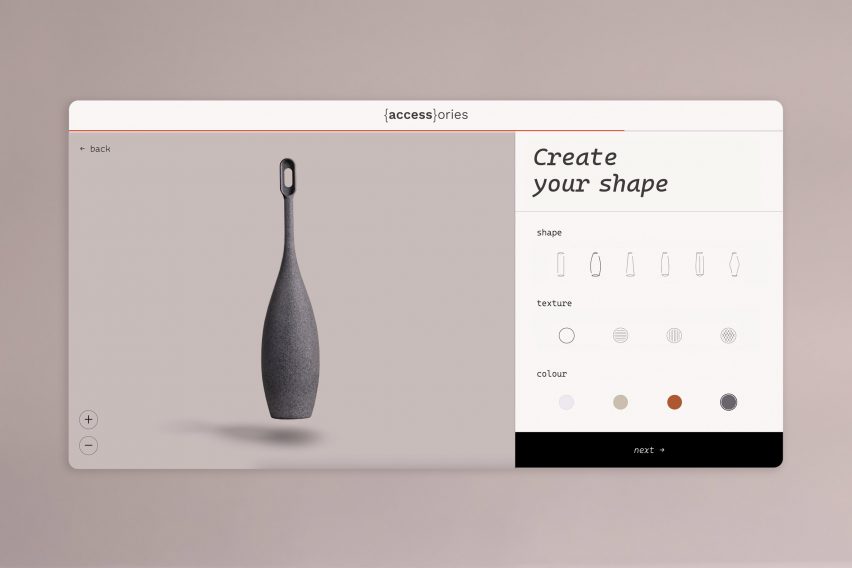

More than 142 different handle designs feature in this range of adaptive toothbrush add-ons, created by brand consultancy Landor & Fitch for people with dexterity challenges.

Chunky grips, grips that bulge outwards as if wrapped around a tennis ball and grips textured with grids, ridges or spines are at the centre of the Accessories handles, which are created and 3D-printed bespoke for each customer based on an online questionnaire.

The add-ons attach to the handle of regular or electric toothbrushes to create a larger grip, designed to be not just accessible but desirable.

The combination of form, texture and colour gives the objects a decorative or sculptural appearance, similar to a piece of homeware.

It's a big improvement on how people with limited dexterity have previously had to tackle the task of toothbrushing, according to Landor & Fitch.

The consultancy estimates there are 360 million people living with dexterity challenges worldwide. And those, whose ability to hold and manoeuvre a toothbrush has been impacted, are often having to resort to household hacks.

"Whilst researching accessible design, we came across users hacking toothbrushes in functional but extremely uncomfortable ways," Landor & Fitch's industrial design lead Jack Holloway told Dezeen.

"This was by attaching toothbrushes to hands via elastic bands, using dog toys, lollipop sticks and wet cloths. After seeing this, we realised there was a real problem that we as a creative team thought we could solve."

To develop the product, Landor & Fitch brought together a collective of people with dexterity challenges resulting from conditions such as arthritis, carpal tunnel and essential tremors.

They invited them to participate in co-designing the product in a series of "makers labs" – hands-on workshops where the participants could mould shapes, test prototypes and share their experiences.

The participants were involved in the full process, coming back to test final prototypes and give feedback. They also tested the user experience design of the digital platform, which is an essential part of how Accessories works.

On the website, prospective customers are led step-by-step through a survey that guides them to the best Accessories handle design for them.

The quiz begins with questions about the user's condition and the type of toothbrush they use before asking them what shapes are most comfortable to grip, using household objects as a reference.

"Straight like a can", "semispheric like a bar of soap" or "rounded like a tennis ball" are some of the options in this section of the survey, which Landor & Fitch's brand action and innovation director Emily Price said came directly out of the makers labs.

"We always knew we would need to develop a digital platform to help with both the discovery of shape and grip and the purchase," said Price. "However, what the makers labs unlocked was the insight into how users could best discover their perfect shape."

"On the platform we use everyday objects as part of the diagnosis for users to find their grip. This feature was the answer to one of our biggest challenges: guiding users to the correct shape when they themselves were unsure on what shape would fit them best."

The survey then drills down into what texture helps the customer to grab things better and allows them to pick a colour for their add-on: white, beige, grey or rust orange.

The finalised design – one of 142 possible permutations – is then manufactured through 3D printing, which allows the production to be low-cost and hyper-personalised.

Accessories is now in its beta phase and has been shortlisted for a 2023 Dezeen Award in the health and wellbeing product design category.

Landor & Fitch's global chief innovation officer Luc Speisser recently wrote an opinion piece for Dezeen on simple changes that can make design more accessible, arguing that it was time for designers to include people with disabilities in their thinking as a matter of course.

"We cannot continue to unintentionally exclude the one-billion people living on this planet who are experiencing some form of disability," he wrote.