Tech companies must move away from hype-chasing annual product releases in order to drive meaningful design innovation, writes Sarah Housley.

The economic shifts of the past 12 months have changed the context for innovation and could help both the tech and design industries move towards a less hype-fuelled, more considered process for product development.

It has been said that we are at "the end of free money". Where venture-capital investment used to flow to tech start-ups and scale-ups, spurring innovative products to market and creating many of the platforms that now enable digital culture, this year has seen interest rate rises and bank collapses that have changed the landscape considerably. While this period of "sobering" reshapes the tech industry, it also provides the wider creative sectors with the chance to change how we approach innovation – for the better.

There is increased pressure for breakthroughs to happen more quickly, and for the next big thing to appear

Unfortunately, so far that has not been the reality. According to industry tracker Layoffs.fyi, tech companies have laid off 242,481 employees so far this year. Companies have been busy streamlining: cutting down on employee perks, cutting risky or underperforming products and limiting funding into unproven research areas. There is increased pressure for breakthroughs to happen more quickly, and for the next big thing to appear.

Against this backdrop, the tech hype-cycle is spinning ever faster, and the big ideas offered by the tech industry have ever-shorter lives as a result.

The recent history of technology is littered with visions that are now perceived as having failed because they were hyped beyond all reason and then didn't immediately live up to the expectations created. The biggest example is the metaverse, an idea that was blossoming across tech by 2020 but crystallised into a mainstream bet when Meta's name-change was announced in 2021.

In 2022, McKinsey valued the metaverse as having the potential to generate $5 trillion by the end of the decade. Global interest in the concept soared and companies across sectors announced chief metaverse officers and full metaverse teams, despite few convincing use-cases having been developed. By May 2023, following a lack of consumer adoption, business magazine Insider had declared that "the Capital-M Metaverse is dead… the latest fad to join the tech graveyard".

With the metaverse and related Web3 ideas such as NFTs now largely in the rear-view mirror – for the moment – the same overinflated hype-cycle is being applied to AI, which is forecast by PwC to be worth up to $15.7 trillion to the global economy by 2030. What these bubbles have in common is that the technology, what it offers, and how it could be applied to products, is kept purposefully vague and broad so as to attract as much excitement and investment as possible.

Even as creatives strive to understand the capabilities of AI and how they might effectively and equitably work with the technology, the bubble is starting to wobble. Semafor's technology editor Reed Albergotti wrote in August: "I was a little surprised last night when a venture capitalist told a room full of tech journalists that AI was already in a 'trough of disillusionment' and that it was hard to find promising start-ups in the space."

Science and tech are reliant on the moonshot ambitions of billionaires and charitable foundations

All this comes at a time when calls are growing for governments to re-commence significant national support of scientific, technological and creative innovations. In the absence of the kind of broad and deep governmental support that led to many of the breakthroughs of the 20th century, science and tech are reliant on the moonshot ambitions of billionaires and charitable foundations, and this is leading to a narrower view of where progress is most important.

A steady-state model of innovation based on continuous, long-term investment would alter the dynamics of the hype-cycle considerably. Research and development teams would be less reliant on gaining the interest of venture-capital funds and more reliant on demonstrating widely-applicable, socially useful research over a longer time period.

This more considered cycle of innovation would create useful friction, allowing time to evaluate the ethical implications of a technology or product in more detail, including its environmental and social impact. Too often, this work has to be done in the aftermath of innovation – as is now happening with generative AI – as ethics-focused researchers work to catch up to implementation. It would also open up time for the design of products and services to move beyond minimum viable product, to become higher-quality experiences that meet the needs of more diverse groups of people.

For designers, slowing product release cycles would make room for meaningful advances rather than putting pressure on brands to either hype up iterative updates as revolutionary progress, or forcing teams to come up with something ostensibly new and exciting for the sake of filling a press event.

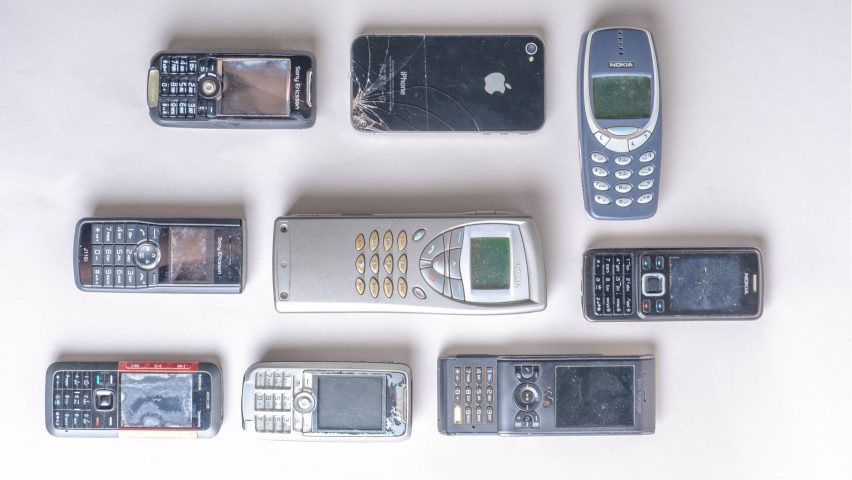

Smartphones are a prime example. According to a 2023 Deloitte study, 3 in 10 smartphones in the UK are now at least 30 months old, suggesting that the upgrade cycle is slowing, even as tech brands continue to launch new devices every year and introduce new formats, such as foldables, to maintain consumer interest. Andrew Lanxon, editor-at-large at tech website CNET, has called for brands to release new phones less often in order to lessen their environmental impact and "make phones exciting again."

Brands have started to adjust their approach, but the economic incentive of an annual release cycle makes it difficult to break entirely. Notably, at Apple's September launch event the iPhone 15 received a grand unveiling but the event's other big headline was the company's sustainability update, which included the announcement of a carbon-neutral Watch.

For much of the 21st century, tech has owned the idea of innovation in the eyes of the public

The tech industry, as epitomised for the past few decades by Silicon Valley, has built its reputation on introducing exciting new ideas that shape how we see the future and how we want to live our lives. For much of the 21st century, tech has owned the idea of innovation in the eyes of the public, and brands may see moving away from the hype-cycle completely as an existential threat.

But over-accelerated hype-cycles are creating a bubbly and unstable innovation landscape in which meaningful advances are overshadowed, sustainability is sidelined and design approaches that value long-term positive impact are swept aside. It's time to rethink the cycle, and invest time and resources where advances really matter.

Sarah Housley is a writer, researcher, consultant and speaker specialising in the future of design and ethical innovation. She is former head of consumer tech at trend forecaster WGSN.

The photo is by Rayson Tan via Unsplash.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.