A person can change the prescription of their eyewear with a quick swipe with the 32°N sunglasses by technology company DeepOptics.

The adaptive focus sunglasses use a technology that DeepOptics calls pixelated liquid crystal (LC) lenses.

These lenses contain thousands of pixels, which in this case refers to tiny electronic controls that change the optical properties of the glasses.

The new technology can have many applications, but with its first product, the Israeli company is targetting people with presbyopia — a condition that affects everyone as they age, making it progressively harder to focus on objects up close.

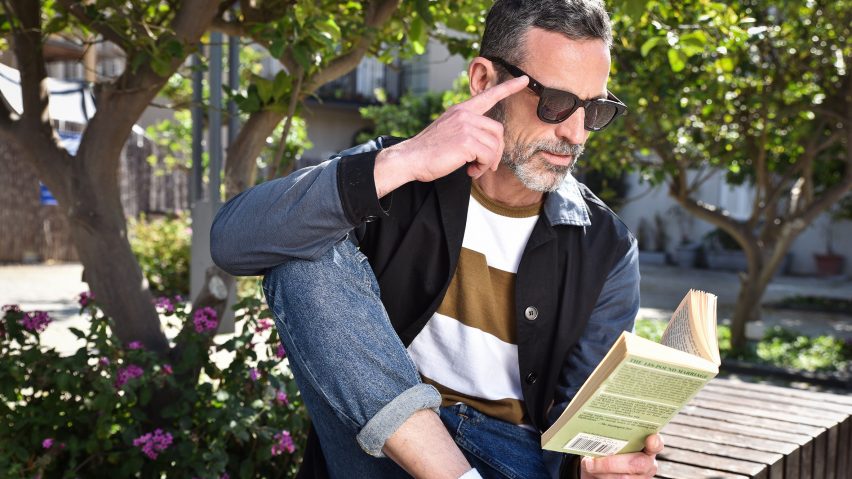

Whereas usually affected people would face switching between two pairs of glasses while outside — one pair of sunglasses and one pair of reading glasses — with 32°N, they only need to swipe the arm of the frame near their temple to trigger a change in the lens.

"With dynamic lenses, the lenses can dynamically change their prescription — their optical power — to correct for different distances," DeepOptics CEO and co-founder Yariv Haddad told Dezeen.

He explained that while there are other technologies out there for dynamic focusing optics, almost none of them are suitable for eyeglasses because they rely on moving parts.

"Liquid Crystal is a material that can change its optical characteristics electronically, without moving or changing its shape, and is therefore critical for enabling this new generation of adaptive eye glasses," he said.

He said the technology adds almost no weight or bulk to the glasses, and has the added advantage of being updatable with new magnification profiles over time.

With presbyopia, a person's prescription increases gradually until it stabilises around the age of 65 to 70, meaning that they would usually go through several pairs of glasses, but the prescription for the 32°N sunglasses is set via an accompanying app and can be updated later on as needed.

This feature should enable the 32°N glasses to stay in use for longer than many regular eyeglasses, even though the addition of electronics often shortens an object's lifespan.

The secret to the technology is the liquid crystal lens, which Haddad says is designed and built similarly to a transparent version of the liquid crystal display (LCD) screens used in TVs and smartphones, and features a liquid crystal layer on top of a matrix of pixels.

"These pixels are actually tiny electronical controls that apply local voltage to the liquid crystal layer that in turn, changes its refractive index," said Haddad.

"When powered, they generate a very precise and complex 2D voltage profile that resembles a shape of a lens, and affects the liquid crystal differently at every point."

Haddad says the pixels can be thought of as "drawing" the shape of the lens on the liquid crystal layer, with different small voltages determining the instruction they give.

A small processor, battery and Bluetooth chip are embedded in the injected polymer frame to make the product work, with only a small amount of power required to activate the adaptive focus lenses.

The 32°N sunglasses are shortlisted in this year's Dezeen Awards. DeepOptics next plans to bring the LC lens technology to eyeglasses for people with myopia as well as presbyopia, so they can toggle between their far-sight and reading prescriptions.

People often wear bifocal or progressive lenses in this instance, but those can have their drawbacks as they divide the lens into different sections for multiple uses.

The company is also working on a model that switches modes automatically rather than manually, using data from eye-tracking sensors in the glasses frame to gauge whether the wearer is looking at something close up or in the distance.

Other recent innovations in eyewear have included smart glasses for streaming video anywhere by Viture and frames specifically designed to fit Black faces by Reframd.