Stockholm Furniture Fair "created a testbed for new ideas"

With trade shows falling on hard times, this year Stockholm Furniture Fair set itself on a new path. Dezeen editorial director Max Fraser explores whether other fairs can learn from the Swedes' approach.

Stockholm's annual design showcase took place this month against a backdrop of recession in Sweden when many are questioning the efficacy of the traditional trade fair format and the Stockholm Furniture Fair itself is set to be sold.

"How do we activate the fair for the future?" asked the fair's director, Hanna Nova Beatrice, at the opening. "How do we instigate new energy? And how do we do so in a recession?"

Once considered the main launch platform for Nordic design, Stockholm Furniture Fair has contracted in recent years, with its momentum broken by the Covid-19 pandemic.

And like many fairs around the world, it has suffered as brands' budgets have tightened and they have become more selective about the fairs at which they exhibit.

"Many of us have questioned the need for fairs"

Meanwhile, the concept of shipping bulky products around the world to be displayed on temporary stands is coming under scrutiny amid increasing concerns about the design industry's environmental impact.

"Many of us have questioned the need for fairs," designer and environmentalist Emma Olbers told Dezeen. "I think we'll continue to have a need to meet up, share our knowledge and do business, but in a new format."

In response to these multiple pressures, for its 72nd edition this year Stockholm Furniture Fair consciously took a new direction – one that others around the world could learn from.

"The fair this year feels to me like it has created a testbed for new ideas," said Olbers.

For many years, Stockholm has hosted the trade fair at the city's official venue, Stockholmsmässan, while events took place in showrooms across the city under the banner of Stockholm Design Week.

Fair "merged commerce with culture"

Historically, commerce happens at the fair and experimentation in the city.

But for the 2024 event, Beatrice wanted to change this perception, instead making the fair the centre of visitors' attention, a place to have fun.

"This year, we merged commerce with culture under one roof," she explained. "One of the things that we were asked by all of our exhibitors was to create a more relaxed and happy feeling."

Numerous exhibitions and three bars were opened at the fair. It required considerable investment at a time when revenue from exhibitors is down – but Beatrice believes it was a necessary survival tactic.

"We believe there is no better way to fight a market downturn than to meet it head on – and network in a design bar," she said.

At Surface Club, the bar designed by Malmö-based Studio Lab La Bla, the enormous and playful space doubled as a mini golf course and hosted popular afternoon DJ sessions.

Those searching for calm headed to the Reading Room installation in the show's entrance, created by the fair's 2024 guest of honour Formafantasma.

The Italian studio's co-founders, Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, designed a tranquil space cloaked in dusty pink curtains.

Here, visitors could rest and read publications that have contributed to the studio's pioneering material investigations. As Trimarchi put it, "It's a bibliography on our way of thinking."

"The big and boring ones such as Kinnarps chose to abstain"

In the show itself, many significant Swedish names were missing from the exhibitor line-up, including furniture brands Kinnarps, Offecct and Swedese.

Furthermore, with Copenhagen's citywide 3 Days of Design event providing an alternative lure for brands in the region, there was a lack of Danish brands exhibiting in Stockholm.

There were still plenty of strong exhibitors on show, however, including Wästberg, Hem, Vaarnii, Massproductions, Johansson, Edsbyn, Blå Station, Gärsnäs, Verk, Wekino and Ishinomaki Laboratory.

Beatrice treated the absentees as an opportunity to pepper the show with installations and exhibitions, while those who were exhibiting viewed it as an opportunity.

"At this year's fair, there were still a few furniture companies that happily believe in the future and have invested in it with new materials and products," said design consultant Anders Englund, working on the revived Swedish furniture producer Edsbyn.

"The big and boring ones such as Kinnarps chose to abstain and sent their biggest customers to all of us who were promoting our news at the fair."

The organisers have sought to trade on that sense of positivity in order to build up loyalty among exhibiting brands. They have placed a particular emphasis on attracting the design community back in and giving them a platform.

"For us, the fair is really important," said Färg & Blanche co-founder Emma Marga Blanche. "We would never be where we are today without the fair. We can do installations and things that we couldn't do somewhere else."

As well as exhibiting, the Swedish studio designed The Yellow Thread bar and the main talks auditorium at this year's fair.

Emerging designers exhibited collectively in prominent positions around the fair. The long-running Greenhouse area gave recent graduates and design schools a professional forum to exhibit.

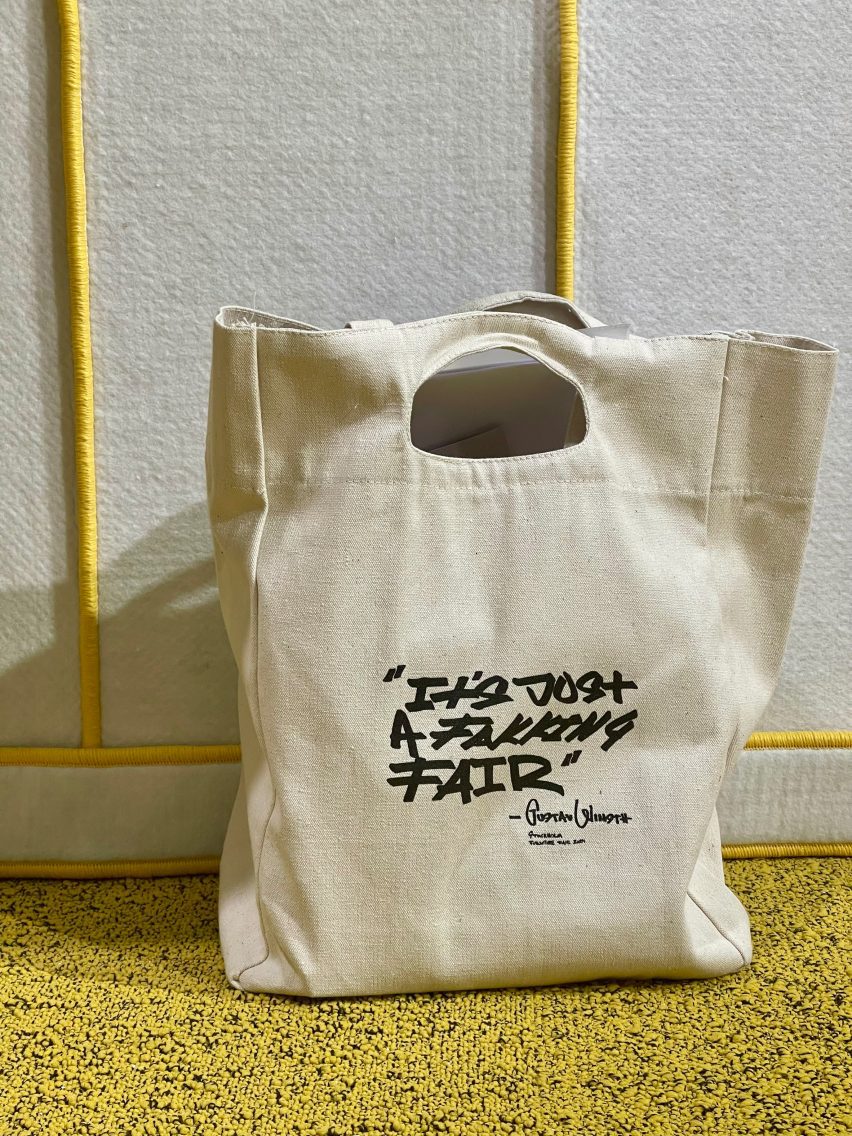

Independent designers and makers were given a gallery-like setting in the Älvsjö Gård showcase and first-time exhibitors were bunched together in an area called New Ventures, including Niko June, NM3, Gustaf Westman Objects and Swedish Girls.

Other highlights included the prominent Farming Architects exhibition by Jordens Arkitekter. The practice moved their studio into the fair, built a full-size timber and hemp pavilion and assembled natural building materials to show alongside project case studies.

The space communicated a refreshing manifesto for future living and demonstrated the links between sustainable architecture and regenerative agriculture.

"It's going to be quite interesting to see if this fair becomes very local"

All of these interventions, including a packed talks programme, helped to interrupt the monotony that can often come when navigating aisle after aisle of commercial brands.

Despite its innovations, Stockholm Furniture Fair's future remains uncertain after it was recently announced that it will be put up for sale by the city, with the current exhibition centre set to be demolished to make way for new housing.

"It's quite interesting to me, weird even, that they can say something like that if there is no alternative venue for it," said Italian designer Luca Nichetto, based in Stockholm.

"Considering what is happening in Scandinavia, it's going to be quite interesting to see if this fair becomes very local, or if there is still a hope that it remains relevant in an international field, as it was before."

Others were less concerned.

"I think it's positive in one way, because the City of Stockholm has owned it before and that is complicated," designer Alexander Lervik told Dezeen. "I think [a new owner] will be able to do much more."

It is clear that Beatrice and her team have been working hard to change the fair's fortunes and this year's edition felt like the make or break moment for the Stockholm Furniture Fair.

The show may be smaller than in previous year's, but as design fairs grapple with the post-pandemic landscape this more compact, more curated, more energetic experience could set a fresh trajectory for the Stockholm Furniture Fair to bloom again.

The main photo is by Andy Liffner.

The Stockholm Furniture Fair took place from 7 to 11 February 2024 in the Swedish capital. See Dezeen Events Guide for more Stockholm Design Week exhibitions in our dedicated event guide.