Making a built environment that works for everyone will require the end of profit- and ownership-obsession in the industry, argues New York-based architect and researcher Emanuel Admassu in this interview.

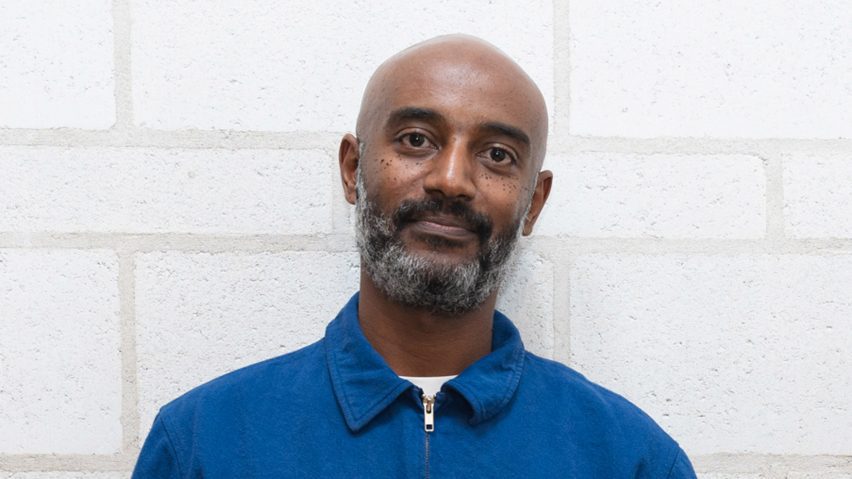

Admassu is a co-founder of art and architecture practice AD-WO and an assistant professor at Columbia University, where his research focuses on the entangled relationship between spatial justice and land ownership and value.

He believes that in order to deliver more equitable buildings and public spaces, a complete rethink of the economic and legal structure surrounding architecture is needed.

"I think we can centre spatial justice within the practice of architecture by finding a set of concepts and ideas that help us think about space-making differently," Admassu told Dezeen.

"We have to really confront the legal formations that foreclose any other way of making space or sharing space."

"Dismantling that value system is going to take a lot of work"

Admassu, who works in New York, Addis Ababa and Melbourne, acknowledges the scale of the task he is proposing.

"Whether you go to Addis Ababa, or Dar Salaam or New York, the assumption is: you buy that lot, you build on that lot, and you continue to generate some capital, right?"

"So redirecting that or dismantling that value system is going to take a lot of work."

As a starting point, he believes in experimenting with new mechanisms for delivering buildings that challenge the status quo but can still work within it.

"We have to keep inventing other tools, and those tools have to operate within a world that is already enclosed," he said.

For example, he points to shared or community land and others ways of "collectively stewarding land".

The very concept of land ownership itself is problematic, Admassu contends.

"The displacement or the dispossession of indigenous communities starts by measuring the land and absorbing that land into a particular worldview that says land is something that has to be owned," he said.

"For us, the intervention really begins there – by really thinking about measuring, because measuring in the history of architecture has been deployed in order to divide and own."

Instead, Admassu is interested in how the concept of "immeasurability" can deliver architecture projects that are more "about sharing the planet than they are about owning the planet".

He refers to urban marketplaces that are often formed by "spatial negotiations" – and therefore more difficult to portray in the form of conventional plans and sections – as an example of immeasurable sites.

Admassu's investigation into these topics is reflected both in the work of his studio AD-WO, founded in 2015 alongside Jen Wood, and his teaching at GSAPP, Columbia University, which he says are mutually informed by one another.

After moving to the US from Addis Ababa at the age of 15, Admassu studied architecture at Southern Polytechnic State University in Georgia.

He grew particularly interested in the more theoretical aspects of architecture and how they related to his own lived experience, which eventually led him to a thesis exploring urban marketplaces in Africa while studying Advanced Architectural Research at Columbia University.

He now maintains an ongoing research project specifically investigating two urban marketplaces, in Dar es Salaam and Addis Ababa.

"Based on my lived experience and moving through the marketplace in Addis, I knew these were incredibly sophisticated spaces that had their own value systems, and ways of organising things and negotiating space," he said.

Admassu explains that the project grew from his frustration around how "dominant architectural discourse was only able to look at cities in Africa, or maybe even broadly cities in the Global South, as informal spaces".

Instead, Admassu identifies these places as "subversive spaces" that serve as examples of his vision for a built environment not focused on ownership and capital.

"There are tools within these marketplaces that help us imagine a world after property," he said.

These "tools", he explained, chiefly concern the conditional agreements between merchants and city officials over the use of space in the markets.

Global North architectural concepts "just get plopped into Addis Ababa"

Admassu's research has also explored the role of traditional fenced zones or compounds in Addis Ababa – known locally as Ghebbi.

These zones differ from developments in other climates and social contexts that have hard-lined definitions between indoor and outdoor, and public and private.

Instead, the Ghebbi are "porous environments", Admassu explained, penetrated by both residents of the compound as well as neighbours, friends and relatives – reflecting a central part of Ethiopian community culture.

Admassu wants to see these concepts adopted in more of the modern buildings springing up around Addis.

"Unfortunately, like any city in the Global South, there are a set of references that come from elsewhere that just basically get plopped into sites in Addis Ababa."

AD-WO highlighted this topic through an installation titled Ghebbi at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2023.

Previously, the studio has also featured in an exhibition at MOMA titled Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America, exploring themes of spatial justice in Atlanta.

"That quickly led us to an investigation of property, and how property continues to foreclose various ways of being together, and various ways of imagining cities differently," he said.

The aim, he explained, was to ask, "what would it mean to really imagine architecture after property, or to disentangle architecture from property?"

"It's a question that evades easy solutions."

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.