Is a plastic-free future possible?

With Earth Day 2024 and an increasing number of environmental campaigners calling for an end to plastics, is time finally up for the 20th century's miracle material? Rima Sabina Aouf finds out if we can – and should – abolish plastic.

Earth Day 2024 has the theme of "Planet vs Plastics", campaigning for "the end" of the material starting with a 60 per cent reduction in plastic production by 2040 and ultimately building to a "plastic-free future".

"Better to incinerate plastic than recycle it"

The proposal is indicative of a broader escalation in the rhetoric around plastic.

In the face of mounting evidence of dangers to the health of people and planet, and with lobbying efforts ramping up as United Nations member states work towards a draft of a global plastics treaty by the end of this year, more abolitionist voices are emerging, and even clashing with campaigners for circularity.

Sian Sutherland, co-founder of advocacy group A Plastic Planet and alternative materials database PlasticFree, is among those who believe we should put an end to plastics – recycling and all.

"It is better to incinerate the plastic – safely – than it is to perpetuate its toxic existence by recycling it," Sutherland told Dezeen.

"We need to take plastic out of our system wherever possible. And if we burn it, despite the fact we are simply burning fossil fuels that were momentarily a bottle or plastic bag, we are taking it out of the system."

She points out that at the current rate, global plastic production is forecast to increase threefold by 2060, and that the reality is that little of it is recycled – around 5 per cent in the US and less than 10 per cent in the UK.

She also backs a recent report from the Center for Climate Integrity, which claimed that the plastics industry has spread disinformation about the efficacy of recycling as a sales tactic in the same way that oil companies have more famously obscured the climate impacts of fossil fuel.

"Recycling is the fig leaf of consumption," added Sutherland. "Makes us feel better but never actually fixes the problem. It simply prolongs it."

"We have mostly stopped material innovation"

Plastic-abolitionists like Sutherland argue that only binding phase-out commitments will channel investment into developing viable alternative materials.

"The answer to the 'is it possible' is this: for the last 50 years we have mostly stopped material innovation, because we had this miracle called plastic," said Sutherland. "It has become the default for almost everything – products, packaging, building materials, textiles."

Labelling plastic a "toxic, indestructible material", she adds that a ban would create "a vacuum that innovation will quickly fill with better, safer, nature-compatible materials".

"The odds are against all innovation whilst we still swallow the myth that recycling plastic is (a) happening and (b) the answer," said Sutherland.

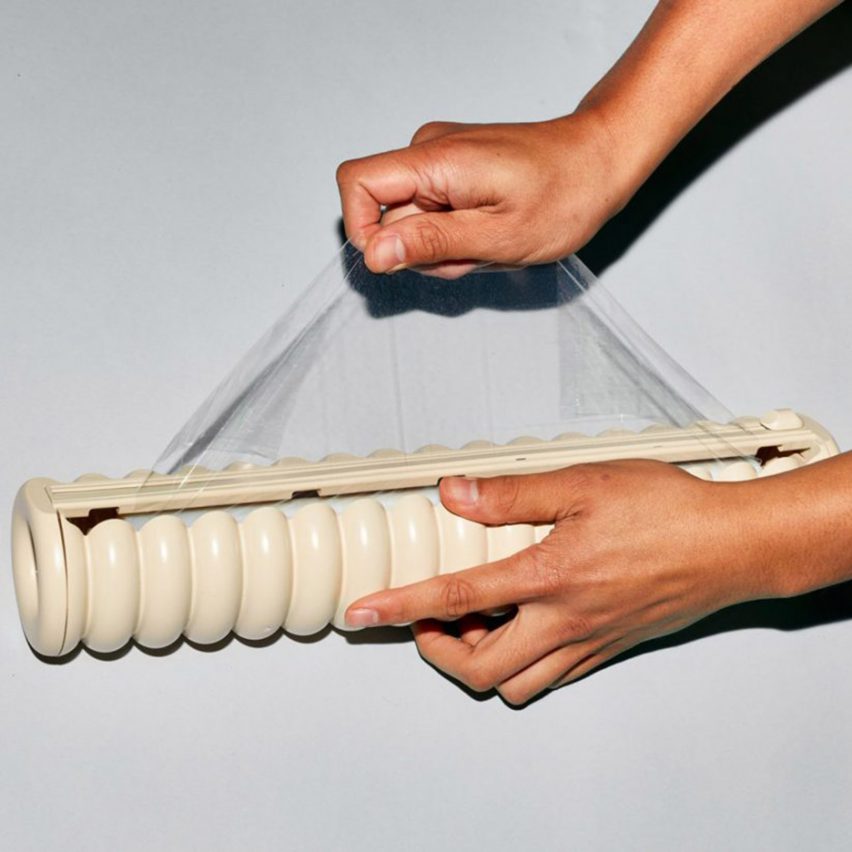

Relevant technologies are beginning to emerge. Bio-based and biodegradable solutions made from crop waste, vegetables, mushroom mycelium, bacteria-forged cellulose and algae seek to emulate the light and pliable qualities that make plastic so integral to modern life.

Some designers are making do with what's already available. Richard Hutten, who at the 2019 Dezeen Day conference described plastic as "the cancer of our planet" and recycling as "bullshit", has managed to design almost entirely without plastic for years.

"Almost", because plastics – polymer-based materials usually derived from petroleum or natural gas – are so ubiquitous they're in products we don't even think about.

"The only plastic I've been using is paint on steel," Hutten told Dezeen. "It is almost impossible to avoid plastic completely."

In recent years he has made a barstool for British manufacturer Modus from cork and redesigned mid-century classics by Wim Rietveld with a mix of biodegradable latex and coconut hair in place of plastic foam.

"Plastic is not bad, it's just completely overused"

But for other environmental advocates, the idea of eliminating plastic misses the real problem: that most of the world today does not value the recovery of materials, of any type.

We may be able to replace every variety of plastic in time, but as long as we live with overconsumption and disposability we will continue to deplete the planet's resources, they argue.

"Plastic is not bad," Thomas Matthews partner and sustainability expert Sophie Thomas told Dezeen. "It's just completely overused, and we don't have the proper infrastructure to get it back in the system."

She points out that from its beginnings in the 1950s, plastic has been sold to consumers as a throw-away luxury that represented progress after the sacrifices of the second world war, when countries including the UK had strict salvage campaigns to collect household waste for reuse to make weaponry and counter slowdowns in imports.

"Every material had to be given back – bones, paper, string – everything had to go into the war effort," Thomas said. "So now this plastic comes along and it's like, don't worry about it. Use it once, throw it away."

"This is the kind of positive, clean, quick, cheap, colourful future that we wanted to bring in after the war."

Instead of changing those patterns of use, Thomas sees brands and manufacturers rushing to replace plastics in the name of sustainability, sometimes with alternatives that have a worse environmental impact.

One example is substituting plastic takeaway containers with paper, usually with a plastic lining that can't be separated, making both materials unrecyclable.

By contrast, PET and especially HDPE – two commonly used packaging plastics – are the easiest to recycle, when not fused to other materials.

"Complexity is the worst thing for recycling," said Thomas. "Monomaterial is the way we should go – bio-monomaterials especially."

Not all plastics are the same, and Thomas does advocate for banning some of them, such as PVC – widely used in construction – and polyurethane foam.

Both, she says, are difficult to recycle and full of "nasty" volatile organic compounds.

Design studio Layer recently developed the Mazzu Open mattress, which swaps out polyurethane foam for less toxic and more recyclable polyester-wrapped springs.

"Polyester is incredibly durable and has a long life – and it's this quality that makes it a useful material in design, as designing for longevity is one of the most powerful tools we have in terms of sustainability," Layer founder Benjamin Hubert told Dezeen.

"Foam has a much shorter lifespan before it loses its functionality, and – unlike polyester – is not recyclable. The trade-off for us here is really clear."

"All recycled plastic ends up as waste"

Much of the debate around abolishing plastics comes down to recycling.

While glass or aluminium can be recycled infinitely without degrading, the molecular structure of plastics gets weakened every time they go through the extrusion process until they can't feasibly be used any further. For single-use plastics, in particular, that means a very short lifespan.

For abolitionists, the compromised quality of recycled plastic makes it misleading to label the process "recycling" at all – hence Hutten's "bullshit" claim.

"In the most optimistic view, you could call recycling of plastic down-cycling," he said. "Eventually, all recycled plastic ends up as waste."

"It will never be a financially and materially viable solution," added Sutherland. "There is no economic model that makes sense – or to be honest Coca-Cola would have built the system years ago to recycle their 120 billion bottles every year."

Those who think there is still a place for plastic advocate for longer-life products within a system where collection and recycling can be guaranteed.

Recycled-plastic design brands such as Circuform and Smile Plastics call their furniture and sheet material circular as they can be recycled repeatedly – four times at a minimum, according to Circuform.

PearsonLloyd co-founder Luke Pearson, who focuses on circularity, agrees that plastic can be "mostly circular" if designed "intelligently".

By avoiding additives such as glass fibre, limiting colour, and adding a small amount of virgin plastic when needed for strength, existing material can be kept in the system for a very long time, he says.

As for chemical recycling – the expensive, hazardous and energy-intensive new technology that breaks down plastic to its basic building blocks so it can be remade with its original strength – Thomas believes it could one day serve as a final step to close the loop on plastic, after mechanical recycling options have been exhausted.

"We have to develop the infrastructure for plastic where you actually get that closed loop, otherwise you will have to go for a complete ban of the material," said Thomas.

"And then what? We'd have to plant huge amounts of trees if we're going to substitute with paper or any crop-based biomaterials."

"There really is no time"

Plastic-abolitionists and circularity advocates agree on a number of points: we need legal restrictions on single-use and toxic plastics, we need funding for biomaterials, and we need to change habits.

The upcoming UN plastics treaty provides an opportunity to realise these proposals. But while some sense momentum towards positive change, longtime plastic abstainer Hutten admits that he has lost some of his optimism.

Recently, he created his first plastic piece in years: a one-off cupboard called Atlas, named after the Titan in Greek mythology who carried the world on his shoulders.

In his "reversed Atlas", a comment on the futility of design in tackling the pollution crisis, the Earth is depicted as collapsing under the weight of humankind.

Sutherland, meanwhile, is in high gear trying to get provisions such as cuts to production volumes of plastics, bans on single-use items and mandated chemical testing into the UN treaty.

"We need to leapfrog the 'less bad' to 'regeneratively good' in all materials and systems now," said Sutherland. "There really is no time for any other approach."

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.