Christien Meindertsma develops linoleum tiles that can be remolded "like playdough"

Dutch designer Christien Meindertsma aimed to rebrand linoleum and establish a new visual language for the misunderstood material with the Flaxwood tiles she has created for manufacturer Dzek.

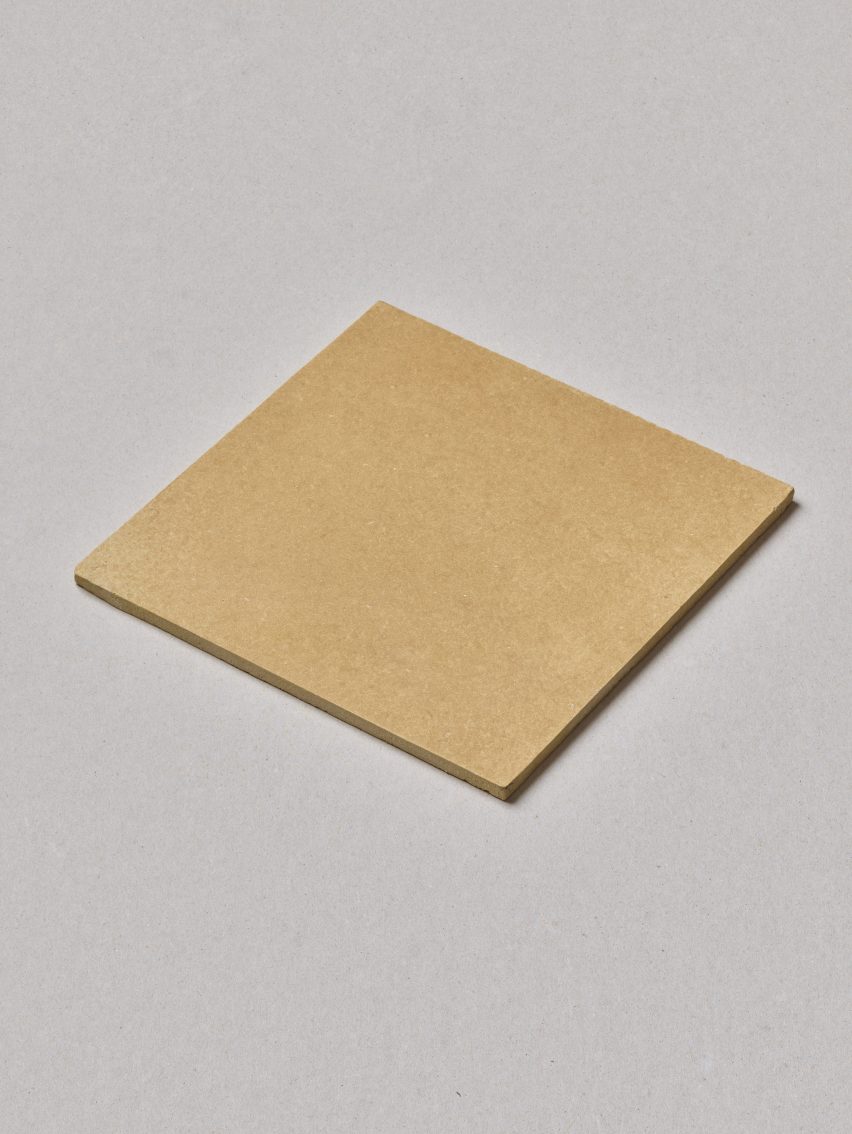

Much like traditional linoleum, the tiles unveiled as part of an installation at Milan design week are made of linseed oil, pine resin, wood dust and chalk.

But in this case, all the pigments, coatings and backings that normally disguise its natural composition are stripped away, creating tiles with a warm honey colour and the mottled texture of MDF.

"Flaxwood is an honest expression of the ingredients that are in linoleum," Dzek founder Brent Dzekciorius told Dezeen. "Linoleum has never been content to be itself, so we wanted to define what it actually looks like."

For the Milan design week installation, the tiles were used to clad a monumental staircase leading to nowhere, designed by Barcelona firm Arquitectura-G.

By showing off the material's unexpected aesthetics and architectural applications, the hope is that the project can help reframe linoleum as a material of the future rather than just a holdover from the 1970s, which it is often perceived as.

Linoleum, unlike plastic-based vinyl and PVC, can be made entirely from renewable and reclaimed materials, as well as being biodegradable and endlessly remoldable.

"It's like playdough or like a bread dough that lasts forever," Meindertsma told Dezeen. "It cures just enough to become something solid but then you can always decide for it to become something new if you need."

"For me, that's really the ultimate thing as a product designer," she added. "I don't know any other material that can do that."

Flaxwood is the result of an ongoing research project from Meindertsma that started in 2010 when she purchased a Dutch farmer's entire harvest of flax – roughly 10,000 kilograms – before it could be exported to China where 90 per cent of European flax goes to be turned into products.

Testing the limits of local production, the designer turned the fibres into yarn, rope, cloths and even a chair, while the seeds were used to make linseed oil and with that an entirely traceable, locally sourced version of linoleum.

The collaboration with Dzek presented an opportunity to resuscitate this research and turn it into an actual sellable product in the form of Flaxwood.

While traditional linoleum is applied to a jute fabric lining and hung up to cure in giant strips, Meindertsma's version is formed using a mould and a pressure press, with no need for a backing.

Also gone are the fossil-derived coatings and pigments that are traditionally used to help linoleum take on different colours and patterns.

"Our process is much more streamlined," Dzekciorius said. "We use a lot less energy."

Still, the current version of Flaxwood is more of a starting point than a finished product, since the raw materials are syphoned off from the industrial production of flooring manufacturer Forbo.

The ultimate aim is instead to create a linoleum that is made entirely using local materials and thus fully traceable.

This would allow the recipe to be customised with different ingredients, using more rapidly renewable plants such as cattail and reed from Dutch peatlands or wood dust from different trees to subtly change the colour of the tiles.

"Linoleum is inherently an incredibly sustainable material," Dzekciorius said. "But there's room for improvement on it."

"Using more fast-growth renewables as material sources is better. And it also leads to other aesthetic outcomes, which makes it really interesting."

Several of Meindertsma's previous tinkerings with the recipe were on show as part of the installation.

One sample was coloured with ground-up old roof tiles and another was made using waste calcium carbonate, which was filtered out by a local water treatment plant, instead of mined chalk.

"So you don't actually have to mine it, you can use a waste stream," the designer explained. "And it's already industrially taken out of the water. So it's really no problem to use that."

There's also the potential to experiment with greater thickness, which gives the material more rigidity and allows the linoleum to be sanded, cut and milled much like a piece of timber.

"It can have this dimensionality, which I think is really antithetical to what people associate with it today," Dzekciorius said.

"It can have a density that is kind of similar to MDF," he added. "It could potentially be a huge improvement over something like that because there aren't any glues."

But, to reach its full potential, Meindertsma argues the material needs to be accompanied by an efficient closed-loop recycling system, so it can stay endlessly in use.

"An object that keeps changing form – that would be my ultimate dream," she said.

A number of other designers have started reappraising linolem for its sustainable credientials in recent years. Among them is Don Kwaning who adapted the material to form a vegan leather alternative and Eindhoven graduate Lina Chi, who made a series of self-supporting furniture pieces from a single sheet of linoleum.

Milan design week took place from 15 to 21 April 2024. See Dezeen Events Guide for an up-to-date list of architecture and design events taking place around the world.