Melanin-spiked bodysuits provide sun protection in Melwear concept

Garments made with the skin pigment melanin provide a natural, alternative form of sun protection in this speculative biofabrication project by recent Central Saint Martins graduate Maca Barrera.

The Melwear project imagines a future where humans wear a "second skin" embedded with bacteria-derived melanin instead of using conventional chemical sunscreens, which typically contain ingredients that can be harmful to the environment.

The thin suit replicates and amplifies the role that melanin already plays within our skin, providing a barrier against the sun's UV radiation.

Developed as part of Barrera's graduate degree in biodesign, Melwear is based on two emerging technologies: the biosynthesis of melanin within bacteria and the bioprinting of artificial tissues with living cells.

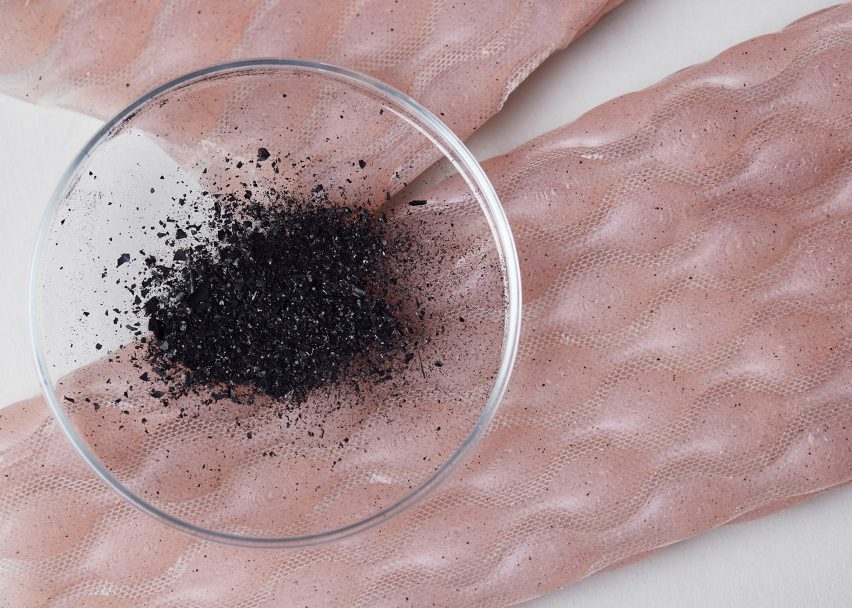

Synthetic biologists are currently growing melanin-producing bacteria in labs and experimenting with various ways to apply or extract the pigment, sometimes using genetic engineering to improve yields.

Although melanin is produced naturally in many species – including some fungi and vegetables as well as animals – the fast-growing nature of bacteria affords an opportunity for the pigment to be cheaply mass-produced.

It can then be used as a biocompatible and biodegradable replacement for toxic synthetic dyes – as pioneered by bacterial dying company Colorifix – and also has potential applications in cosmetics, biomedicine and materials science.

With Melwear, Barrera explores one of the most unique properties of melanin – its UV absorbency. This absorbency would create sun protection for the wearer of the garment.

Bioprinting, the other key technology explored in the piece, is mainly used for the creation of artificial tissues, with the goal of one day replicating whole organs. By incorporating bioprinting into her project, Barrera is able to imagine additional functionalities for it.

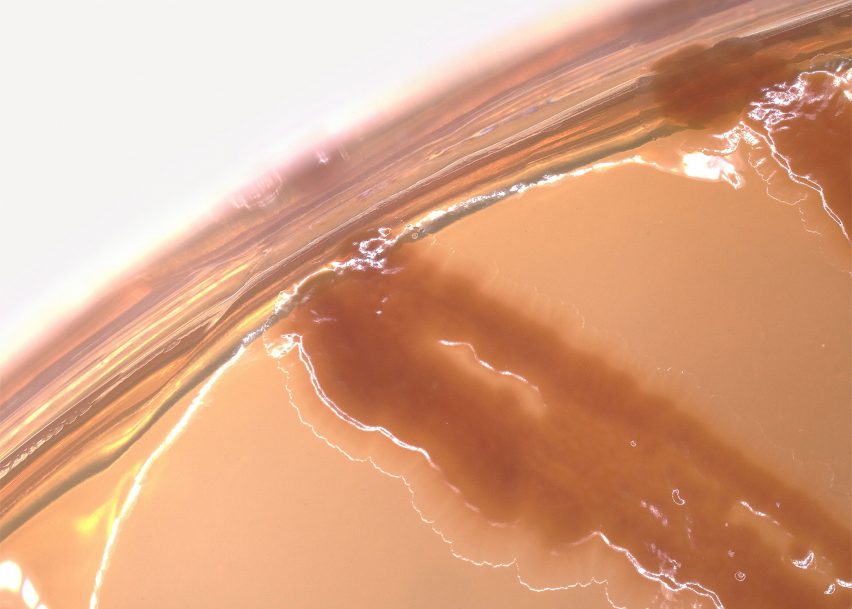

She sees the melanin pigment being printed into capsules in a way that would allow the suit to act as a sensor for UV levels. The capsules would become active and darken in response to high exposures, mimicking the process of pigmentation within the skin but to a heightened degree.

The colour change would serve as a visual indicator of current UV levels – something that most of us are currently unaware of unless we look for the data in a weather app.

Because Melwear is a speculative project, there is no functional prototype. But Barrera worked in the Grow Lab at Central Saint Martins to produce her own bacterial melanin and develop a range of concentrations. She was also able to test out bioprinting technology through a partnership with the Francis Crick Institute.

The designer said she was inspired to embark on the project to explore the connection between the human body, microbes and the environment.

"For too long, we've seen our bodies as capsules, protecting them from all types of microorganisms," she said. "In doing so, we have not only killed harmful bacteria but also healthy microbes that could protect our bodies from pathogens."

"My focus in this project was to reconnect with microbes, learn from them and their biological systems and harness the incredible power of these organisms. They may be invisible to our naked eyes, but they hold the essential power to protect our bodies and preserve our lives."

Speculative projects like Melwear play an important role in starting public conversations around little-understood technologies, according to Barrera.

"It's an opportunity to create future scenarios and solutions that can contribute to scientific advancements to address sustainable challenges," she said. "In this context, Melwear is a speculative project that aims to push the boundaries of what we currently know as UV protection and explore solutions that consider a balance between human and environmental health."

Architect Neri Oxman has also previously used speculative design to explore the potential future of melanin. Her 2019 work Totems imagines the pigment being used in architecture, also to offer sun protection.

At the time, she said the application of melanin and other biological substances in architecture was "inevitable".