Philip Johnson's Glass House guest annexe reopens after restoration

US architect Philip Johnson's Glass House annexe, the Brick House, has been restored and reopened following a 15-year closure in Connecticut.

Lead by architect Mark Stoner and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the project included the exterior and interior restoration of Johnson's Brick House, a small retreat building located just across from the historic Glass House.

It follows the building's closure in 2008 after the structure suffered ongoing "water intrusion" due to its sloping site.

Beginning in 2022, the scope of the restoration included updates to structural and cosmetic elements including improvements to site drainage, cladding and interior finishings, replacement of the roof and skylights, window repairs, artwork conservation and a complete replacement of the building's mechanical and electrical systems.

"For such a seemingly simple structure, the work required to preserve, protect, and restore the Brick House was extensive," said Stoner.

"Damage caused by decades of water intrusion into the building from above and below took a serious toll on the building. And yet, now that the project is complete, most visitors will be completely unaware of the vast amount of exterior and interior restoration efforts that went into this project."

Completed two months before the Glass House in 1949, the Brick House served as a secluded personal and guest retreat for US architect Philip Johnson and his partner David Whitney before their passing in 2005.

It is located 80 feet downhill (24 metres) from the Glass House, separated by a lawn and connected by a stone pathway.

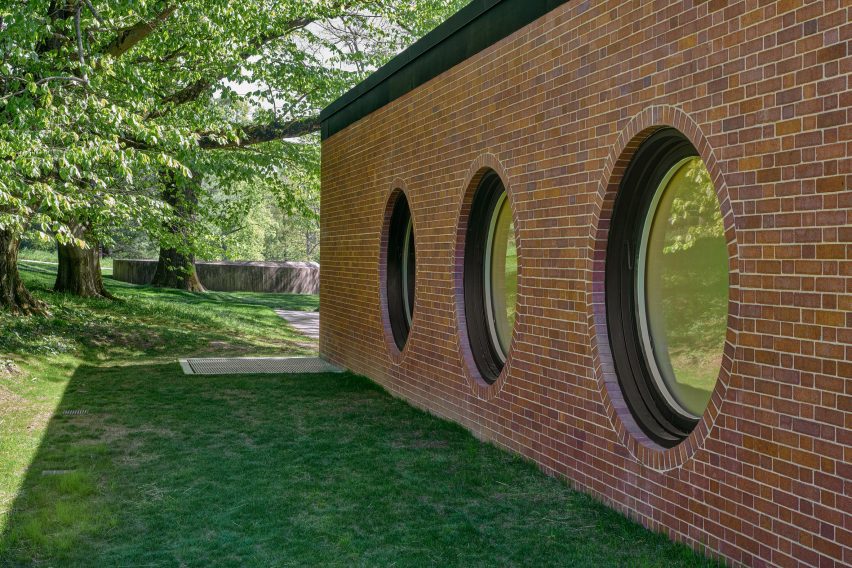

In contrast to the glass walls of its partner, the Brick House consists of three enclosed brick walls, with large porthole windows running along its back. A single door is located on its facade.

It measures half the depth of the Glass House, although both structures are 56 feet long (17 metres).

Designed at the same time, the two buildings were created to serve as standalone wings of one house, combining design strategies from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's Farnsworth House, a freestanding glass pavilion and the architect's court-house concept, which places two rectangular wings at 90 degrees towards one another.

Connected underground, the Brick House serves as an "anchor" to the Glass House and contains the mechanical equipment used to power both structures.

"People have commented there's not much architecture there," said Johnson of the Brick House in a 1991 interview with the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

"There's not meant to be any architecture there. It contains the guest rooms and bathrooms and the necessaries and the heating. So, in that way, we make an anchor for the Glass House."

Johnson's use of brick cladding was also informed by Mies' use of the material, who was in turn inspired by Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

"Mies felt that Schinkel's simplified, neoclassical approach utilized brick in an especially elegant manner," said the team. "So Johnson's use of brick in Connecticut is deeply steeped with historic reference."

The restored version features the layout of the house Johnson renovated in 1953 after moving in, which includes a large bedroom and reading room placed along the porthole windows, and a slim hallway along the front of the house, which also contains a single bathroom.

The interior features an eclectic mixture of materials and furniture throughout, including a purple rug, baby pink and blue chairs by designer Gaetano Pesce in the reading room, and "flattened arches" covered in Fortuny fabric in the bedroom.

"Unlike the Glass House, this structure was a creative canvas where Johnson could experiment with new styles and materials as he made successive changes over the decades," said the team.

According to The Glass House chief curator Hilary Lewis, the bedroom's arches were informed by neoclassical architects Robert Adam and John Soane and are "the earliest example of Johnson's bold move away from traditional modernism".

"Despite Johnson's embrace of his mentor's aesthetic, Johnson had clearly moved away from many of Mies's aspects in both the Brick and Glass Houses, from symmetry to proportioning," she continued.

"Johnson could not help himself from inserting elements of classism and historic reference in both, even in something as minimal as the Brick House."

Earlier this year, Japanese architect Shigeru Ban created a pavilion from paper tubes and milk crates at The Glass House to mark its 75th anniversary.

The photography is by Michael Biondo

Project credits:

General contractor: Hobbs, Inc.

Civil engineering: Landtech

MEP engineering: Altieri Sebor Wieber

Structural engineering: RSE Associates, Inc.

Replacement material: Donated by Fortuny, Inc., Edward Fields Carpet Makers, and Cobble Court Interiors