New York's latest skyscrapers are "disrespectful to the whole city" says Richard Meier

New York is losing its character to a new wave of skyscrapers according to architect Richard Meier, who has also revealed he would consider working for US president-elect Donald Trump.

In an exclusive interview with Dezeen, Meier – who, at 82, is one of America's most respected architects and one of the last of the 20th-century modernists still practicing – said that New York's latest towers are an insult to the city.

"There's a scale to New York as there is a scale to London, and that's what makes the city great," said the architect, whose office on 10th Avenue overlooks the controversial Hudson Yards development.

"That's started changing – the way it is now, it's disrespectful to the whole city," he said. "This is not Kuala Lumpur, it's New York. New York has a quality to it and you have to respect the context."

Meier singled out Rafael Viñoly's record-breaking 432 Park Avenue residential tower and Bjarke Ingels' Via 57 West "courtscraper" for particular criticism.

"It's ridiculous; it's out of scale," he said of Viñoly's supertall skyscraper. "If you want to go out for a bottle of milk, it's a half hour to go up and down. I don't know how people are going to live there."

In the interview, which took place ahead of the US presidential election, Meier also revealed his reservations about Donald Trump – but admitted he would consider working for him if approached.

"I don't think that he's an evil man so there's no reason to not, but I don't know if he'd be a good client," he said.

Born in New Jersey, Meier studied architecture as an undergraduate at New York's Cornell University, going on to work at a number of well-established firms before setting up his own practice in the 1960s.

He was part of the New York Five – a group of architects that included Peter Eisenman, the late Michael Graves, John Hejduk and Charles Gwathmey, who in the 1960s and 1970s championed a purist modernism rooted in the early work of Le Corbusier.

Meier was awarded the Pritzker Prize – architecture's equivalent to the Nobel – in 1984, shortly after completing the lauded High Museum of Art in Atlanta. And one of his early houses, the Douglas House on the bank of Lake Michigan, was put on the USA's National Register of Historic Places earlier this year.

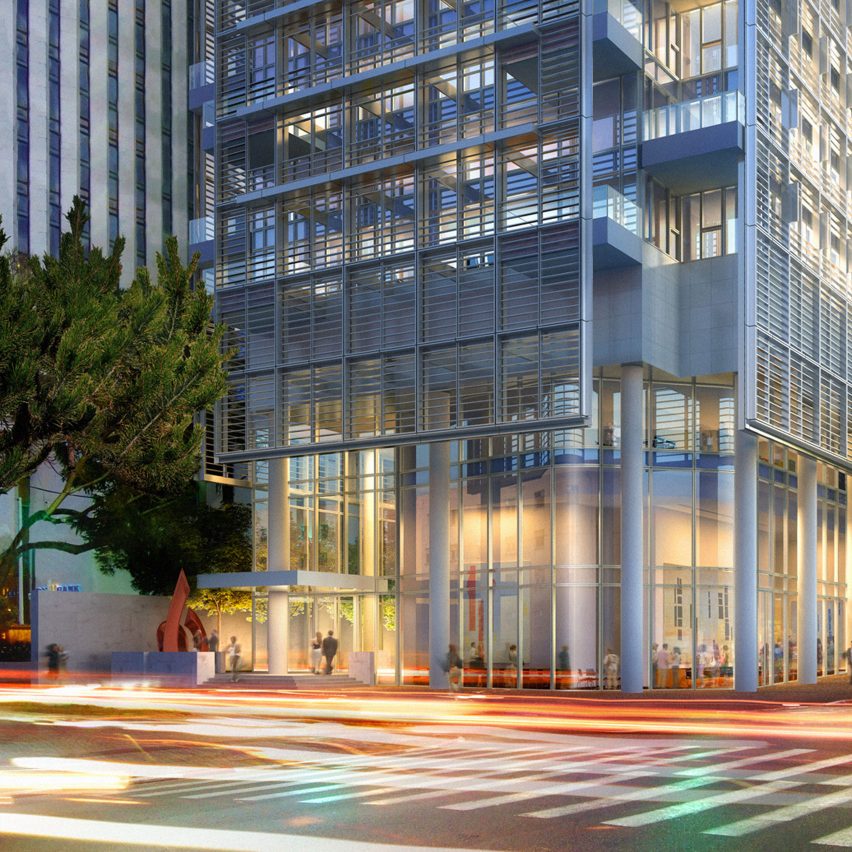

He is known for his use of white, in projects like the seminal Getty Center, completed in Los Angeles in 1997. Today, the buildings designed by his firm follow the same style – predominantly white and glassy, with formal gridded facades.

"When someone comes to me, they're not coming just looking for an architect, they're coming because they know what we do," he said. "They want a certain level of quality and they know we're not going to build a cheap building."

Meier's recent projects include a private home in England for the actor Rowan Atkinson, best known as Mr Bean, the Seamarq Hotel in South Korea and the Leblon office building in Rio de Janeiro.

The firm is currently working on an uncharacteristically black tower for a site on New York's East River, a housing project in Colombia and a mixed-use tower for Tel Aviv.

But the architect said that he had become more of a figurehead for his firm.

"I'm the only one in the office who doesn't have a computer," he said. "I give a drawing to someone and they put it on their computer. Then I mark it up."

Read an edited transcript of the interview with Richard Meier:

Anna Winston: Let's start at the beginning. How did you get into architecture in the first place?

Richard Meier: I decided at quite a young age that I wanted to be an architect. At that time Cornell seemed to be the best choice and it still does have a very good undergraduate architecture program. Most other schools like Princeton, Harvard and Yale have graduate programmes but they don't have a programme for undergraduates. I was in a hurry so I went to Cornell.

Anna Winston: What attracted you to modernism?

Richard Meier: Well we lived in a modern time so it's not like there was a choice really. Contemporary architecture is really the way to express the time in which we live, it's never been a question.

Anna Winston: As you career has evolved, do you think that modernist principles continue to hold true?

Richard Meier: Yes. Architecture is about the making of space. Space we move through, space we exist in, space we share – space whether it's interior space or exterior space. It's a making of a place and that relates not only to our times but to the context in which it's located.

Anna Winston: Since you started out in New York in the 1960s, what's been the biggest positive change in architecture and is there anything that you're not comfortable with?

Richard Meier: I think the main thing that's changed is the scale. I look out the window here and I see the Empire State Building and I can relate to that at the scale of a city, but if I look out another window I think "oh my god". The scale is changing, not for the better.

Even with the Empire State Building, the buildings around it, you feel that there's a context, that they're related. There's a scale to New York as there is a scale to London, and that's what makes the city great – as you walk from one area to another the scale changes and you feel related at ground level to what's around you. That's started changing – the way it is now, it's disrespectful. It's disrespectful to a whole city, so I'm very concerned that everyone's trying to make a taller building here. This is not Kuala Lumpur, it's New York. New York has a quality to it and you have to respect the context.

Anna Winston: What's driving that push to build things taller?

Richard Meier: Probably the cost of land. The land is so expensive you have to put up something to justify the cost of the land. Unfortunately, much of the work that's done by developers, it's just how much money can they make out of it.

You look at the Rockefeller Center and even though the building is tall, there's an open space that's part of it, thank god for that! It's just a little gem that area, how important that is in that part of the city. Then thank god we have Central Park! Without Central Park I don't know what this city would be like. There's got to be a relationship between the built environment and open public space.

Anna Winston: The city does seem to have a particular problem at the moment with the cost of living and housing. There's a lot of very famous architects building very expensive condo towers here right now.

Richard Meier: Yes, it's terrible. We've done housing and continue to do housing, but there's not a public housing programme here any longer. There's no public housing, it's ridiculous, it's all private and it's all unfortunately quite expensive. I can see it from my apartment window, this very thin, tall slender building.

Anna Winston: Rafael Viñoly's tower?

Richard Meier: Yes. It's ridiculous; it's out of scale. You must spend, I don't know how much time, going up and down in the elevator. If you want to go out for a bottle of milk it's a half hour to go up and down. I don't know how people are going to live there.

Anna Winston: Do you think that cities like New York and London have an obligation to ask architects to create something that is for the social good?

Richard Meier: I think they do. Unfortunately the municipal governments in New York or in London have no programmes for doing housing, everything is done by private developers. I think it's a poor time for public housing.

Anna Winston: What do you think about architects like BIG?

Richard Meier: I was at a symposium maybe a month ago and I was sitting next to Bjarke Ingels. I'd never met him before and there were questions from the audience like "what's your favourite building in New York?"; "what don't you like?", and I said, "you know there's one building in New York I really hate, it's on 59th street in the West Side yard, it's just so unlike and unrelated to New York," and he's sitting right next to me. I said, "This is not personal but that building is just, in my view, so inappropriate."

Anna Winston: What makes it inappropriate?

Richard Meier: The scale of it, the form of it, it's so aggressive. New York is a city that is a grid. This could be out in New Jersey in the meadow lands, it's unrelated to anything.

We're doing these houses in Bodrum and they're very different to a house we were going to do in Connecticut. The climate is different, the relationship of one house to another is totally different, the topography – everything about it – the way they use the house.

Anna Winston: But there's still a lot of glass?

Richard Meier: Oh yeah. And they happen to be white.

Anna Winston: What is it about white?

Richard Meier: Well it's all colours. You get these light changes, you see the colour of nature, you see the colour that's all around us most clearly where the white is. It's never one thing, it's always changing.

You know, when I look back there's nothing I wish I hadn't done. There's some [buildings] I prefer. The public buildings I think are the most important because they get used by the public. Whether it's a museum, like the Getty that continues to get thousands of people all the time. People go back to it, they enjoy being there and that gives me pleasure – that other people get pleasure from experiencing the place. We do a private house, it's just for a couple of people; when you do a public building many people can enjoy it.

Anna Winston: Can I ask who you're going to vote for?

Richard Meier: I'm not going to vote for Trump, I have a hard time voting for Hilary so I thought I would vote for myself as a write-in.

I think I've watched too much television, [Trump] just has the same line over and over and over, it's like a broken record. There's nothing new, it's all the same. I just don't see him being president.

Anna Winston: Trump is interesting because he's a client – he's built major buildings. Would you design anything for him?

Richard Meier: Of course I would, depending on what it is.

Anna Winston: So the next Trump Tower could be designed by Richard Meier?

Richard Meier: I don't think that he's an evil man so there's no reason to not, but I don't know if he'd be a good client.

Anna Winston: Do you still see many of the other well-known architects?

Richard Meier: I see a lot of Peter Eisenman. We used to have sort of regular dinners together – groups of architects, 10 or 12 people – and it was for many years all male. Zaha was the first woman we invited to the dinners and she was as vocal as any of them. Jim Stirling came quite often because he was teaching at Yale. But we haven't done that in a while. I guess when you get older things change.

Anna Winston: You mentioned Zaha, who we lost this year...

Richard Meier: It's terrible. It's a shock because she went in to the hospital for bronchitis, nothing, and then she died of a heart attack. I just don't understand it. Zaha was great, it's just tragic.

In the late 1970s I was on the jury with Arata Isozaki, it was the two of us, for a project, it was called The Peak. We chose Zaha's entry before anyone had heard about Zaha, and that really sort of put her in the limelight, which was great. It was her entry that was by far the best.

Her design was just so outstanding, so unique. You'd look at it and just say, "wow, that's really something wonderful." Unfortunately it was never built.

Anna Winston: She was also a Pritzker recipient, like yourself. What did winning a Pritzker mean to you?

Richard Meier: I think for anyone who has won the Pritzker, it's helped their career. You can't say that all of a sudden the phone rings and you get a lot of work, that's not the case, but I think it's a very positive boost. The publicity that it generates allows your work to reach a wider public than might otherwise be possible. When you look at the list of architects that have won the Pritzker, they've all gone on to do very good work. Maybe they would've anyway, but I think it helps.

Anna Winston: It's a very male dominated list...

Richard Meier: I think the times are different. There's no barriers for women in architecture as there might be in other professions now.

Anna Winston: What do you mean by that?

Richard Meier: I think there's an equality. No one says "oh, I'm not going to hire a woman architect" or "it's man's job", that doesn't exist, at least not here. When we're interviewing people we look at their work, we don't look at whether it's a man or a woman. Zaha was very strong for women's rights in architecture, but her partner is male.

Anna Winston: When a client approaches you, are you looking for something in that client to say, "yes I can work with you," or do you just say "you have the money, fine".

Richard Meier: When someone comes to me, they're not coming just looking for an architect, they're coming because they know what we do. They want a certain level of quality and they know we're not going to build a cheap building.

Anna Winston: How much of your work are you delegating to other team members – are you still the core of it?

Richard Meier: A lot of times, depending on what it is. We have a project in Colombia in South America and we have a very good team working on it, but on a day-to-day basis I don't really get involved and I don't travel as much as I used to. Someone else goes to Colombia and talks to the people there, comes back and tells me the problems we've got.

I'm just a figurehead here, we have a group of people working together all contributing. What we do is not really the work of one person, it's the work of many people working together with a common goal. Architecture is a collaborative effort it's not a singular effort.

Anna Winston: Do you try to keep your office at a certain size?

Richard Meier: Yes. I would say around 50 people, 40 to 60, in that range.

Anna Winston: The layout is quite different from other architects offices that I've been in, where they have those long desks and everyone has a little station. You've got quite a generous space I think.

Richard Meier: That's because we used to make big drawings. Now we're on computer, we have more space than we need but we've left it that way.

Anna Winston: And you still make all of your models in-house?

Richard Meier: Usually if someone comes right out of school we start them in the model shop and after three months they start working on a project. It's a way of them getting to understand the office. For the most part they have to work in the model shop before they go on a computer.

Anna Winston: Do you think that changes their understanding?

Richard Meier: It enables them to sort of see what the process is like, because we build a lot of models of everything, still, even with the computer. One augments the other so it's not one thing or the other. But I'm the only one in the office who doesn't have a computer.

Anna Winston: Do you still sketch?

Richard Meier: Yes. I give a drawing to someone and they put it on their computer. Then I mark it up.

Anna Winston: What do you think of the way that some schools teach now, with students learning to design first on computers?

Richard Meier: Well, I think it tends to generate work in which the students don't immediately know what the scale of things are. I remember when I was teaching at Yale I would go around and a student would show me a drawing. I would say "what's that?" He would say "that's a door." I'd say, "how big is that door?" He'd say, "oh I dunno" and would have to ask the computer. A door is a certain size and the computer is not going to tell you that, you tell the computer what it is.

I think for some young people it's about making images without fully understanding the scale relationship. After a while they learn that. I think if you draw it, you know what it is.

Anna Winston: Is there anyone else you think is at the moment doing particularly interesting work or particularly beautiful work?

Richard Meier: Today there's so many good architects everywhere. I used to be able to say so-and-so and so-and-so, but now wherever you go and in every country there is good architecture being done. Whether it's Asia, South America, Europe, the United States, I think it's a good moment in terms of quality architecture and opportunities that exist for good architects too. If someone does good work, people find them.

People are more interested in architecture than they were 20 or 30 years ago, there's more public press about architecture than there was, more public awareness, people are interested. You travel, wherever you go, what do you do? You look at architecture. Not necessarily contemporary architecture but that tells you about the culture.