Lebanese designers embrace rubbish following Beirut trash crisis

A crisis that saw mountains of garbage fill the streets of Lebanon led to heightened interest in recycled materials, say designers and architects at Beirut Design Week.

Recycled and upcycled projects were in abundance at the annual design event, the second held since Beirut's so-called trash crisis began in 2015.

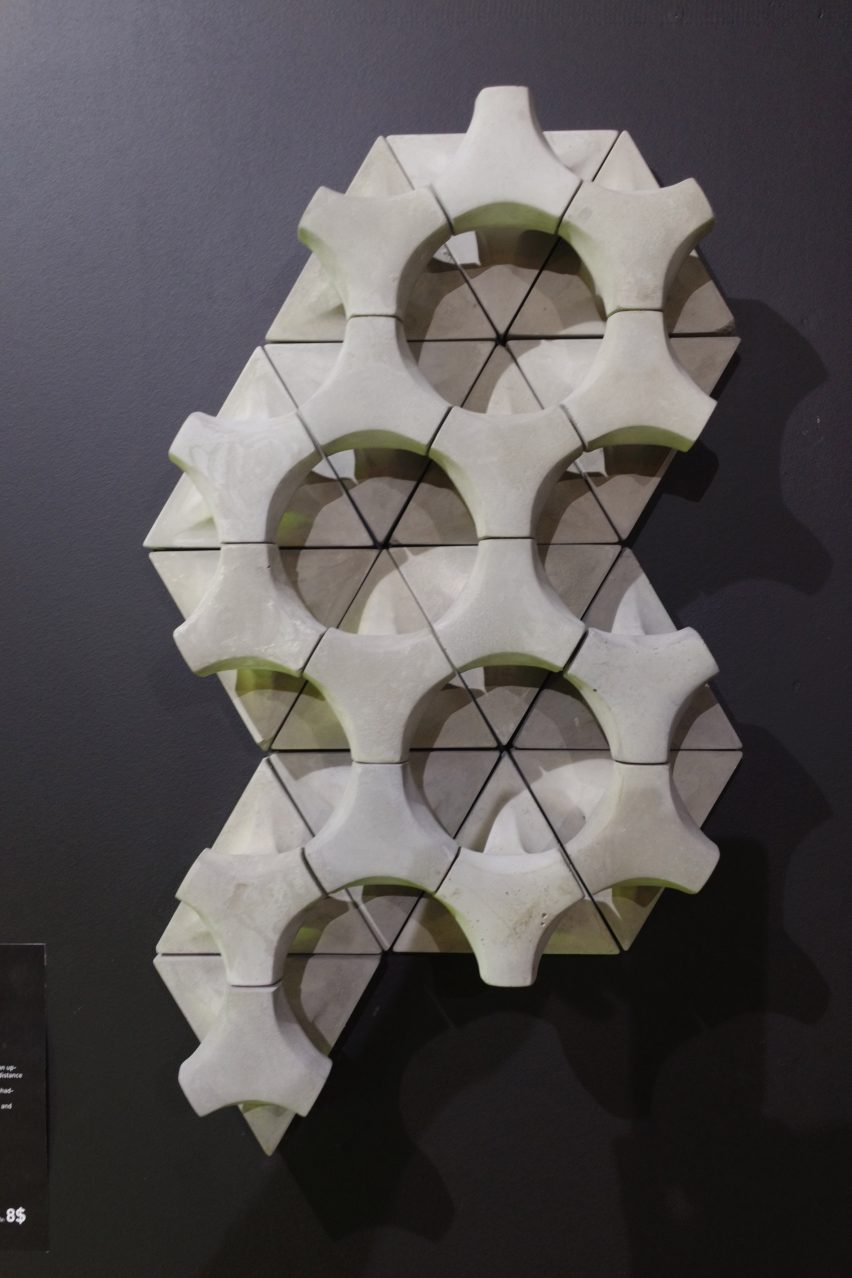

Construction waste was 3D printed into tiles, plastic was recycled into an immersive installation, and used coffee grounds turned up in home accessories during Beirut Design Week, as designers spoke about working with new local environmental organisations to source materials and clean-up communities.

Before this, rubbish had piled up in the capital on and off for two years, triggered by the closure of Naameh – the country's main landfill, which was at capacity – and prolonged by government inaction.

The extreme unpleasantness of living in Beirut during the crisis brought public awareness of the health and environmental problems caused by waste.

"The trash crisis has been a turning point," said Beirut-based designer and architect Guillaume Credoz, who specialises in recycled materials and digital fabrication techniques, and made the construction-waste tiles. "I was already working with recycled aluminium and recycled plastic, but I saw in this crisis a chance to get heard by clients on our choices on sustainable materials."

"I think most designers already knew and were working on sustainable efforts, but the trash crisis gave weight to our argument."

Adib Dada, the head of Beirut's sustainability-focused architecture lab The Other Dada, backs up Credoz' assessment: "In the six years we've existed, this is the first year we've actually had clients actually coming to us because of the environmental aspect. For the last five years, we've had to fight to have those sustainability aspects introduced."

What went wrong

Beirut's refuse woes were caused by a complicated web of factors. With nowhere to deliver the city's rubbish after Naameh closed, the private company that had been collecting it, Sukleen, simply stopped. The country did not have a recycling culture, or a public-space culture, and residents began dumping their garbage wherever they could.

However, most people in Lebanon place the blame on the government – the country is regularly ranked among the world's most corrupt.

In July 2015, protesters led by a group called You Stink took to the streets demanding a government resolution to the problem, but so far there have been only temporary fixes, some highly controversial.

"I would call the crisis ongoing because even though we don't see the trash anymore, it is being sent to landfills to be thrown in the sea," said Dada.

Trash into treasure

Waste popped up in several projects exhibited at Beirut Design Week in May, with many designers naming the crisis as a driving force.

Credoz exhibited tiles 3D printed from concrete and construction waste, Paola Sakr presented vessels made using coffee grounds and newspapers, and Roula Salamoun and Ieva Saudargaite assembled their immersive Nationmetrix installation from strings of recycled plastic.

The new studio Civvies, dedicated to making clothing from waste plastic, displayed its first collection, while older groups like Cedar Environmental's Green Glass Recycling Initiative showed the latest versions of its homeware made by traditional glass-blowers from recycled bottles.

Nationmetrix's Salamoun and Saudargaite said they wouldn't make a temporary work with materials that weren't recycled or recyclable – particularly given the exhibition venue, KED, had itself been next door to an ad-hoc garbage dump at the start of last year.

"Outside this window you could see a garbage mountain that was about 400 metres high, just across the river," said Saudargaite. "You see that every day and you're like, I don't want to contribute any more waste."

Salamoun added: "This is only a temporary project, so if we were going to produce something we can't reuse or transform later, that would have been another contribution to pollution."

Working with communities

The architects and designers of Beirut have not been alone in getting involved in the trash crisis. Without a government-led resolution, a number of organisations have emerged to organise recycling and community projects. They also provide materials and motivation for designers.

Among these organisations is Recycle Lebanon, which organises campaigns and community clean-ups, and Recycle Beirut, a social enterprise that runs a recycling collection.

A third organisation, Beirut Madinati (Beirut My City), was formed in the wake of the anti-trash protests to campaign for a broader range of community causes. It contested the local elections in 2016, and won over 50 per cent of the vote in some city districts.

The designers name check the three organisations as influences, and some of them have been involved in community-based projects. The Other Dada led a clean-up of the lot near KED that had become a rubbish dump last year, turning it into a temporary community garden where locals could partake in city farming.

"We had to bring in eight trucks to take all of the garbage out," said Dada. "And then for two weeks, along with about 20 volunteers, we proceeded with cleaning up the area by hand – excavating, planting, bringing in stormwater management, making solar panels, tagging the wall with messages that people could see from the highway."

"The garden was only there for a month, but the trucks don't dump rubbish there anymore."