It was "a howling error" that the iPhone didn't win Design of the Year in 2008, says Deyan Sudjic

Design Museum director Deyan Sudjic, curator Glenn Adamson, architect Farshid Moussavi and Dezeen founder Marcus Fairs reflect on the difficulty of predicting the impact of design, in this movie produced by Dezeen for Beazley Designs of the Year.

Now in its 10th edition, Beazley Designs of the Year is an annual awards programme and exhibition run by London's Design Museum to celebrate significant designs from the previous 12 months.

In the movie, Design Museum director Deyan Sudjic admits that one of the defining designs of the last decade was overlooked for the top prize.

Apple's original iPhone, which Dezeen editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs describes as one of the "outstanding designs of the 21st century so far" was nominated in 2008. But it lost out to the Yves Behar-designed One Laptop Per Child project, an affordable laptop aimed at children in developing countries.

"Of course, we did make a howling error – the iPhone was not Design of the Year in the year in which it was launched," Sudjic says.

"The One Laptop Per Child project got the top award – a very worthy and worthwhile idea that you could actually deal with illiteracy and the disadvantages of the third world by making laptops cheap and available. It was a bold idea but, of course, in the end it was the smartphone that won everywhere."

Despite not having the same global impact that the iPhone went on to have, Fairs, who was on the jury that year, defends the choice to recognise the One Laptop Per Child Project.

"It did genuinely feel like a potential game changer, but for various reasons it didn't then fulfil its promise," he says. "But it at least symbolised a desire to change."

Fairs believes that designs that are not wholly successful can still change the world for the better. As an example, he cites the Better Shelter flatpack refugee shelter by IKEA, which was named Design of the Year in 2016, but subsequently had to be redesigned following safety fears.

"What do you do? You go back the drawing board, you improve, you iterate," he says. "[Maybe] somebody else steals the idea. So I would imagine that better housing for refugees will emerge from the fact that somebody put themselves on the line and made a stab at it."

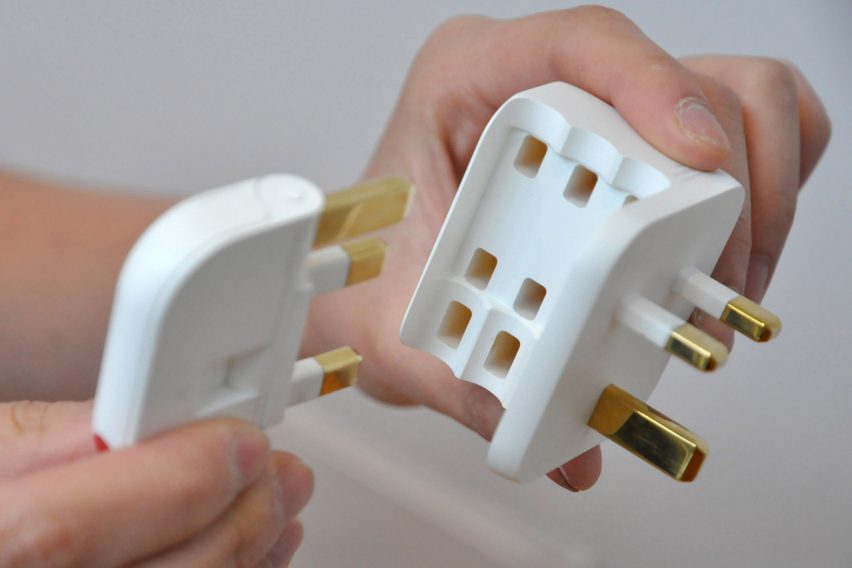

The Design of the Year is chosen from nominations from across six categories: architecture, digital, fashion, graphics, product and transport.

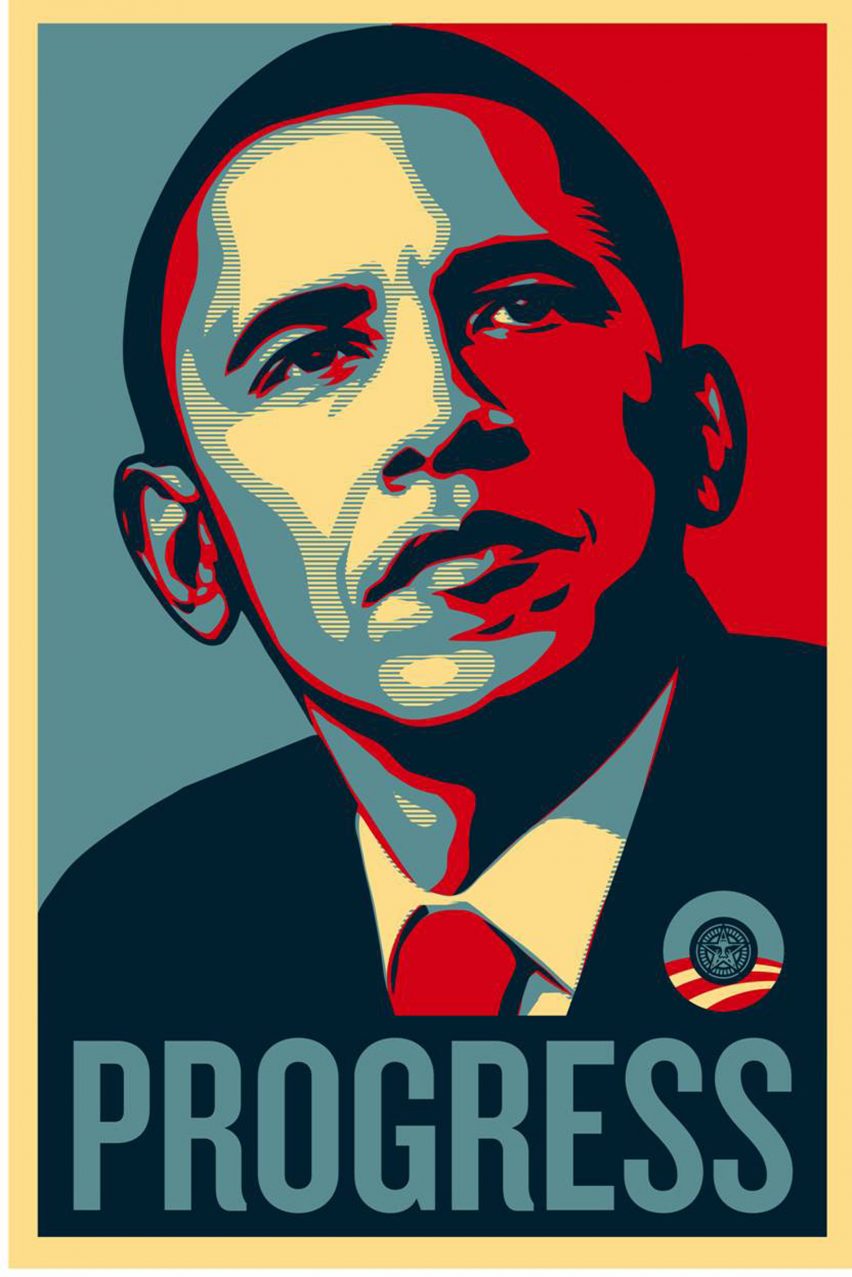

Previous winners of the overall Design of the Year award include American artist Shepard Fairey's poster of Barack Obama, which came to represent the optimism around his election in 2008.

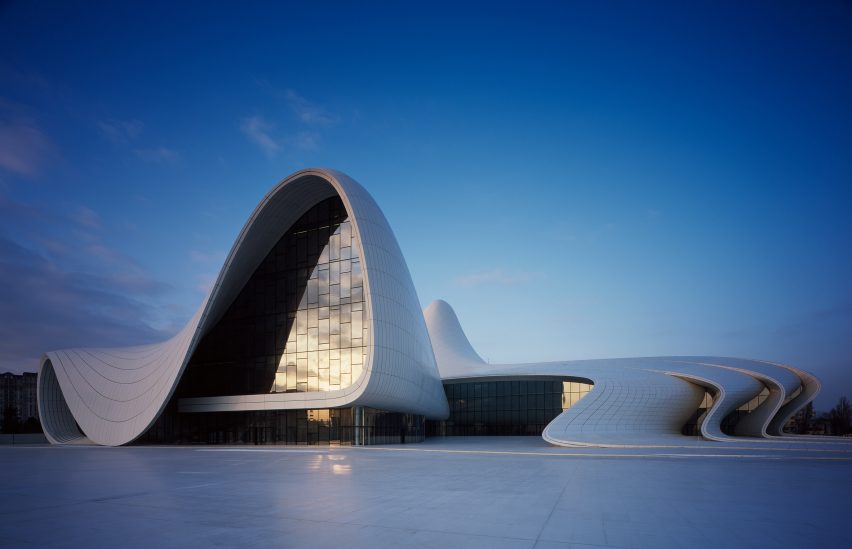

Other past winners include the Plumen 001 energy-saving lightbulb by Samuel Wilkinson and Hulger, Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby's London 2010 Olympic Torch and the late Zaha Hadid's undulating Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku.

Architect Farshid Moussavi, who was on the Design of the Year jury in 2015, says that design has the power to change the way we live in large and small ways.

"Design has every power to bring forth change of different scales," she says. "The internet has had an amazingly global scale of change, but I think there are smaller scale changes that can really transform the way we live."

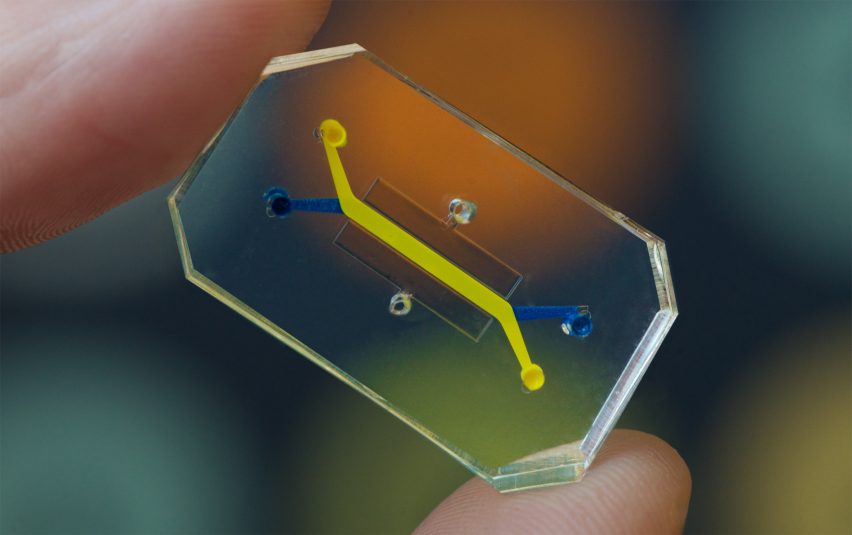

In 2015, Human Organs-on-Chips won the top award, a series of microdevices developed by researchers at Havard University's Wyss Institute, which replicate the functions of human organs for drug testing.

"The potential of it is enormous," Moussavi says. "It was a great candidate because there is a certain extravagance and formalism attached to the word 'design', whereas in this particular case it was almost an invisible object."

According to Fairs, the designs that have the biggest impact on the world are increasingly invisible.

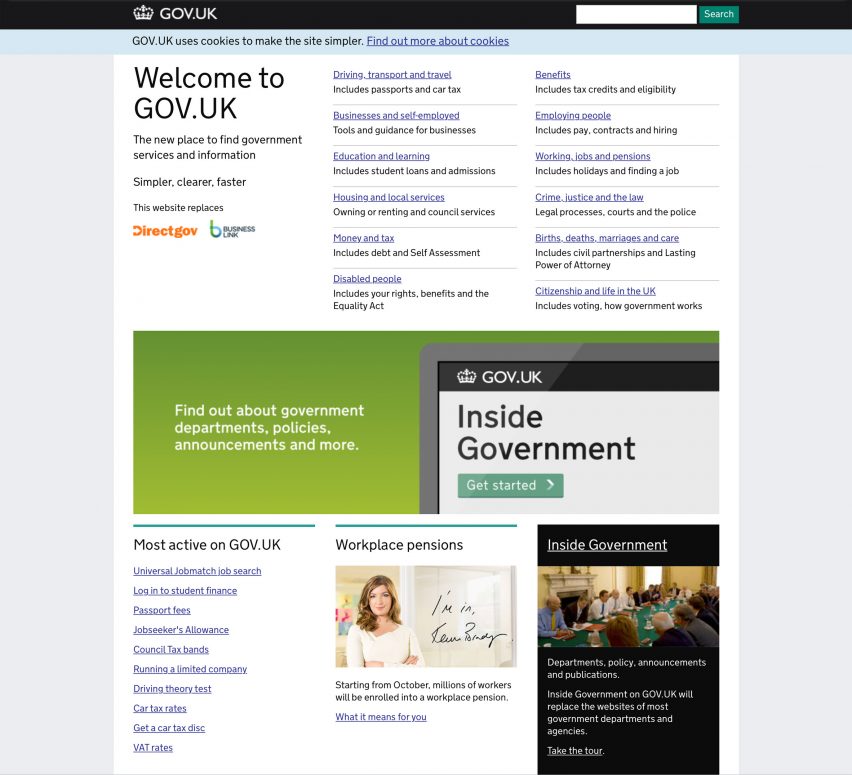

"A lot of the things that are truly transformative are digital, they're in the ether," he says.

"There is no 'thingness' to them. So it's very easy to miss the importance of service design and apps and new ways of encrypting things, like Bitcoin. Cryptocurrencies may well change the way that all financial transactions are made."

"So a lot of the things that should be counted as good design can never be put on a plinth at a design museum or published in a design magazine."

For Beazley Design of the Year guest curator Glenn Adamson, the designs that end up having the biggest impact on the world are often surprising. He cites the impact of shipping containers as an example.

"Design is a funny thing, sometimes it has its biggest impact in places you don't quite see it and it can be very difficult to know in advance what's going to have the real effect," he says.

"The impact, for example, of 3D printing – which was very exciting when it first emerged – in some ways still seems to not have had the transformative effect that one might have expected. Whereas, you think about something like shipping containers – they have become more and more pervasive and in a way that maybe a lot of people don't quite notice they have totally transformed the way that we live."

Sudjic adds: "[The shipping container] brought in its train a complete transformation of every port city in the world that had an upstream dock, because it made them redundant and unusable. So you could say the shipping container produced Canary Wharf, London's business district."

An exhibition of the 62 nominations for this year's Beazley Designs of the Year opens at London's Design Museum on 18 October 2017 and runs until 28 January 2018. The Design of the Year will be announced on 25 January 2018.

This movie was filmed in London by Dezeen for Beazley Designs of the Year, as part of our media partnership for the annual awards programme and exhibition.

All the images are courtesy of the Design Museum, unless stated otherwise.