Graduates design responsive devices to help animals survive extinction

Postgraduate designers from the Royal College of Art and Imperial College London have developed a set of tools that inform animals of potential human threats.

Duncan Carter, Mick Geerits, Arthur Gouillart and Eirini Malliaraki created the advanced bio-logging tags for humpback whales and collared peccaries – a small mammal found in South and Central America.

The tags enable the animals to "reclaim and change their own habitats", by not only passively monitoring behaviour and environments, but also actively informing them of potential human threats.

The graduates designed the tags as an alternative to current conservation efforts, which are largely passive, to encourage people to take a more proactive approach to conservation – rather than lessening our intervention with nature.

"It is generally understood that the resilience of ecosystems is reliant upon its biodiversity," the graduates told Dezeen. "Currently a lot of conservation efforts approach nature as a static system that we shouldn’t interfere with."

"However, the extinction phenomenon we are witnessing has its own momentum, and just mitigating our impact won't suffice," they continued.

"We aimed to redefine human-animal interaction by designing for the animal and ecosystem, as opposed to using a human-centred design process that has become the standard in design."

Having all studied the Innovation Design Engineering programme, run jointly by Royal College of Art and Imperial College London, the graduates worked closely with scientists to develop the high-tech bio-logging tags.

The tools work in a similar manner to existing bio-logging devices, but have an added interactive layer that can communicate with the animal.

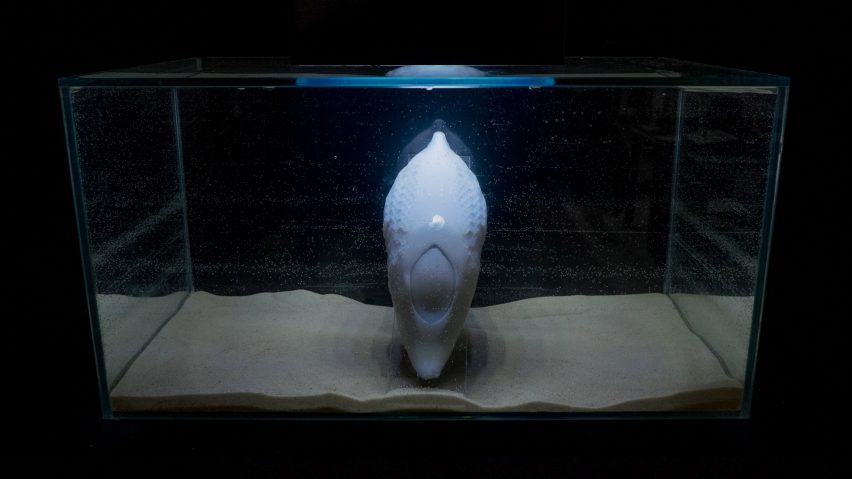

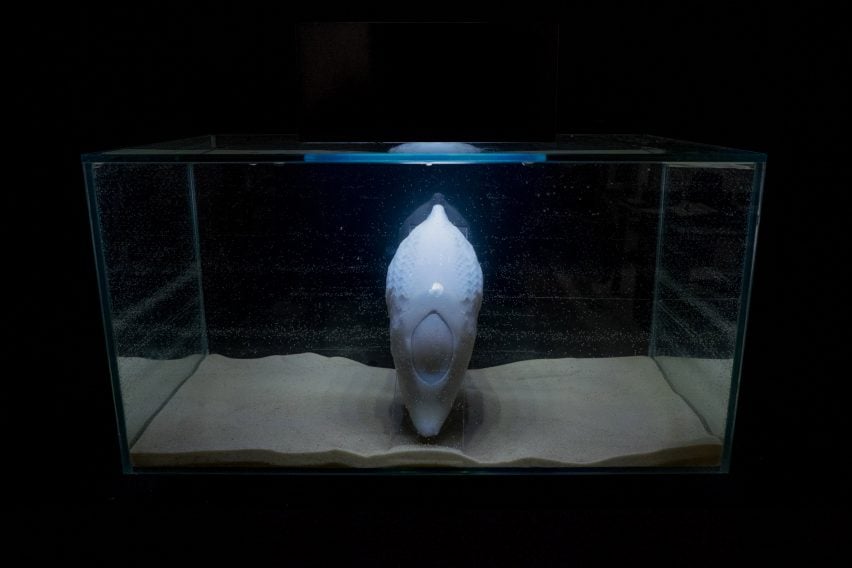

The first device is designed to help humpback whales. Despite being crucial to the ocean ecosystem – as they transfer nutrients to the water's surface supporting hundreds of micro-organisms – the whales are endangered in certain areas.

Attached to the animal in the same way as current data-logging tags – using suction cups – the device has an integrated underwater speaker to actively communicate with the whale through sound prompts. These sounds can signal the approach of ships encouraging the animals to move to safer areas and create new habitats outside of shipping routes.

The second tool is designed for a small pig-like species called the collared peccary and is attached pain-free by a collar.

By emitting vibration signals to convey information about the forest, the bio-tag guides peccaries towards deforested areas where they can disperse seeds, enabling them to build habitats and avoid human threats such as farms and poaching zones.

"We chose to design for these animals because they are ecosystem engineers," said Gouillart. "Like humans, they engineer their environment, but not only for their own benefit, they also bring food and shelter to other species when doing so."

While the two devices are similar, they are sightly modified for the different animals. The whale bio-tag has a hydrophone embedded inside it to reduce the turbulent noise made by fast moving water. It also has a latticed structure to reduce material use and weight, while also improving the grip of its silicone skin.

The peccary bio-tag, on the other hand, features a camera in its centre, and has an onboard computer-vision algorithm running on a chip

The bio-logging tags are still in the experimentation phase, undergoing tests to ensure that they are safe and effective to use.

According to the graduates, vibration motors have already been proven to work on pigs to prevent them from trampling their piglets, and researchers have already carried out tests such as playing certain sounds to whales using an underwater speaker – which they responded to.