Diagrammatic paintings by Japanese architect Shusaku Arakawa go on show in New York

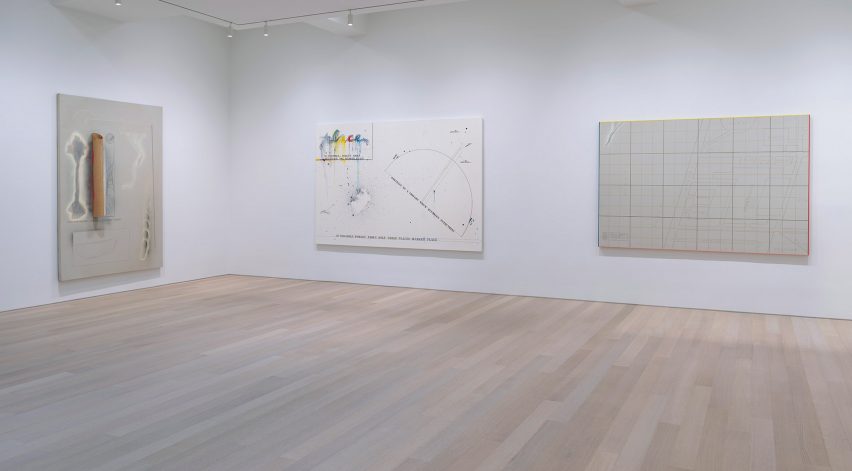

An exhibition featuring the painterly, diagrammatic drawings by Japanese architect and artist Shusaku Arakawa has opened at the Gagosian gallery in New York.

Diagrams for the Imagination showcases the paintings Arakawa created while working as an artist in New York City between 1965 and 1984 – predating his architectural career.

Ealan Wingate, the director of Gagosian New York, spent the last four years gathering the material for the exhibit. Many of the works had been placed in storage in the late 1980s and have rarely been exhibited to the public since.

"This is the first time in all these years to look at the paintings," Wingate told Dezeen. "It's not that I've been holding onto it and waiting for the moment. It finally happened that the moment could come."

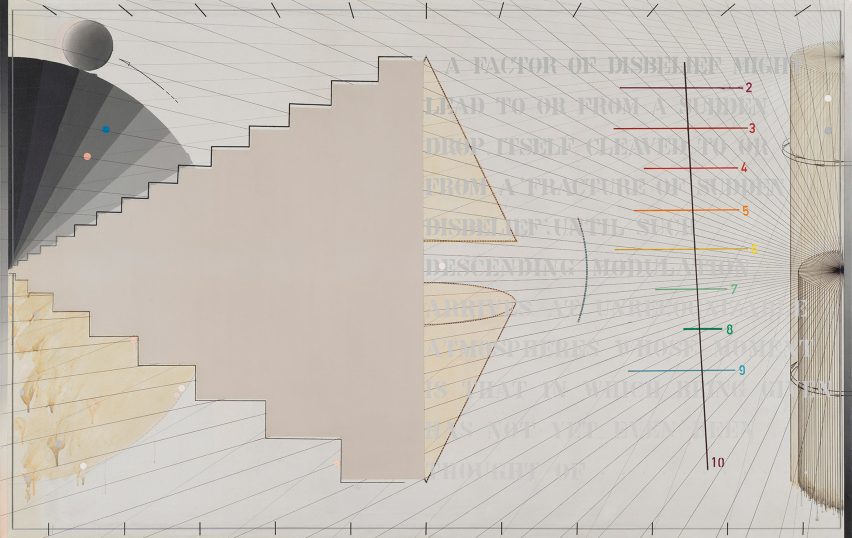

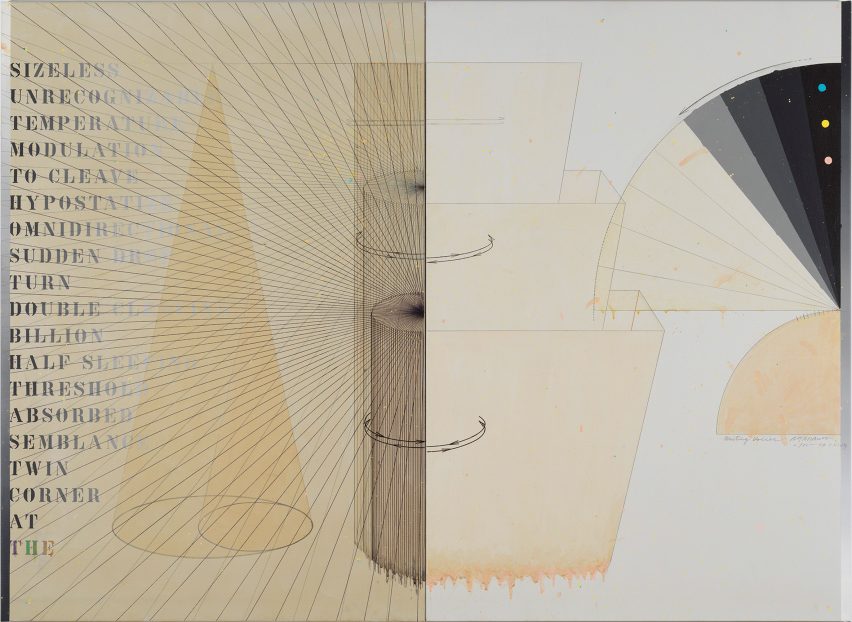

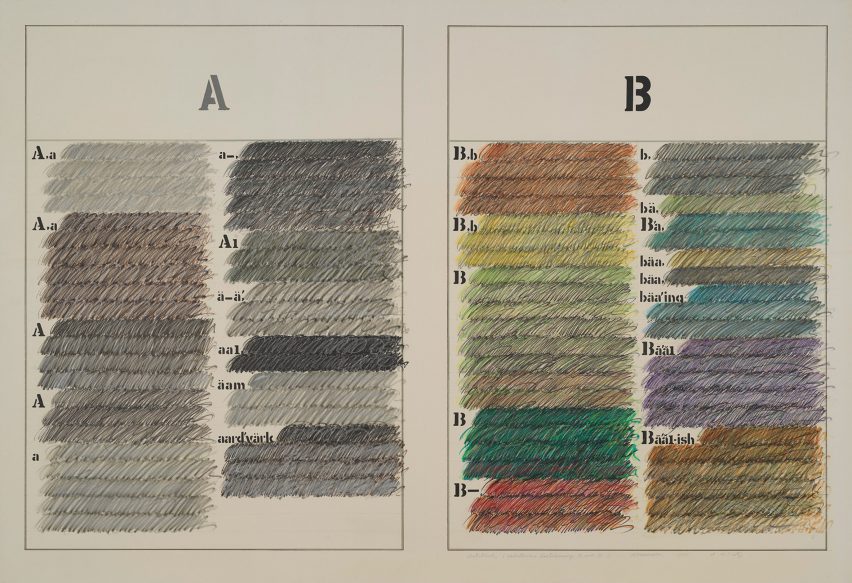

Described by Wingate as a "major artist", Arakawa typically used a mixture of paint, ink and graphite to create abstract, graphical diagrams on paper and canvas. The works are often peppered with text, eye-exam charts, arrows and scales.

"These paintings are diagrammatic and he has referred to them as diagrams of the mind," Wingate said.

While the artworks were created before Arakawa's architecture endeavours, which began in the 1990s, some of the paintings nod to architectural representations.

A Couple No 2, for example, offers a bird's eye view of a bedroom, drawing similarities to a floor plan. Arakawa's piece, however, is detailed with smudged paint and split in two.

One side is annotated with text to indicate the locations of the bed, table, pillow, head, foot and lamp. The other shows these elements as numbers but with the addition of yellow paint to represent light streaming in from a window.

"There is a great breakdown of diagrammatic information, much like one would see on an architectural plan," Wingate said. "[But] whereas an architectural plan would indicate constructions, these are postulating points of view, rather than walls."

The experiential quality of Arakawa's paintings invites the viewer to question what is represented, rather than as a factual source like an architectural drawing or diagram, according to Wingate.

"A lot of what is indicated in the paintings, are aspects for us as the viewer to grapple with," he said, adding that these more abstract aspects draw on the work of conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp, who was a good friend of Arakawa's.

"A lot of Arakawa's work, although not dependent on, is inspired by the breakthroughs that people like Marcel Duchamp made in the early teens and twenties, in which we have that which is told on a canvas, or piece of paper, is not necessarily the truth."

Another work in the exhibit includes Blank Lines, or Topological Bathing, which features a colour chart, an eye-exam test, and two off-white canvases covered in curved arrows and smudges, all pieced together.

The image That in Which No2, meanwhile, merges diagrammatic shapes like stepped forms, cones and cylinders, with scales, grids and dripped paint.

Diagrams for the Imagination documents the final portion of Arakawa's artistic career, which he left in order to pursue architecture with his wife and collaborator Madeline Gins.

Born in Japan in 1936, Arakawa established himself as an artist in Tokyo in the middle of the 20th century.

He was one of the founding members of the Neo-Dada Organisers art group, which followed the absurd styles of the Japanese Neo-Dadaists, and was set up in response to the political climate in Japan at the end of second world war.

Arakawa left the Japanese capital for New York City in 1961, when he also made a transition from his previous artistic endeavours.

Diagrams for the Imagination runs 5 March to 13 April 2019 at the Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, New York City.

Earlier this month, the gallery presented a Marc Newson exhibit at its Chelsea location, featuring pieces that the industrial designer created with Japanese swordsmiths, Czech glass makers and an American surfer.

Photography of individual works is by Rob McKeever, copyright Estate of Madeline Gins and courtesy of Gagosian.