Useful/Beautiful exhibition at Yorkshire stately home asks if craft is still relevant today

Contemporary craft by makers such as Studio Toogood, Max Lamb and Anthony Burrill have been woven into the grand interiors of Harewood House as part of its first craft and design biennial.

Titled Useful/Beautiful: Why Craft Matters, the exhibition explores the relevance of craft in today's digital age.

Opened on 23 March, it showcases work created by 26 makers based in the UK. The exhibitors range from small independent craftspeople working in solo practices, to companies that hand-make products on an industrial scale.

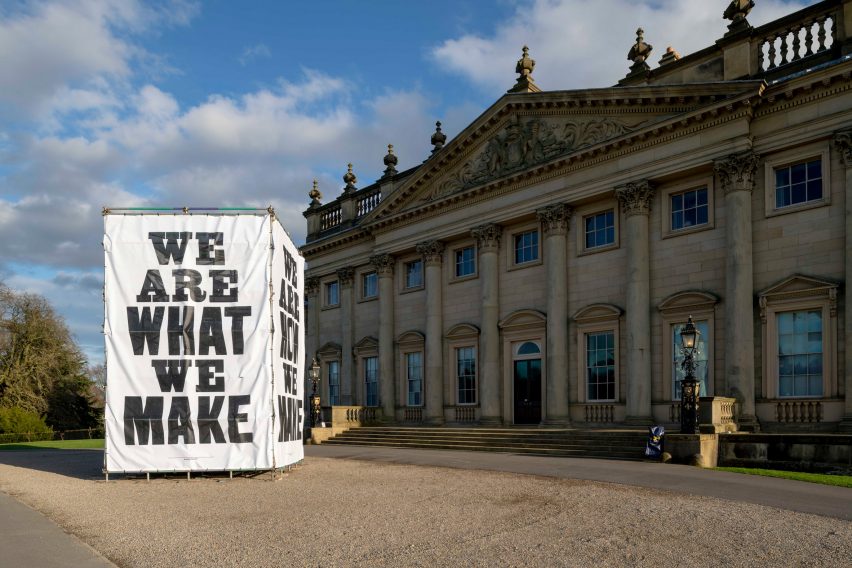

It takes place at Harewood House, a country estate seven miles from Leeds city centre in Yorkshire that was built in the 1780s as a show home.

Harewood brought together commissions from some of the finest craftspeople in the region at that time, including furniture designer Thomas Chippendale and interior designer Robert Adam. Today the house is run as an educational charitable trust.

Working with Jane Marriott, director of Harewood House Trust, design critic Hugo Macdonald was invited to curate an exhibition that could help the house to engage contemporary craftsmen in the way it did when it was first built.

"It's a very interesting proposition to show an exhibition in a house rather than a gallery," Macdonald told Dezeen. "I think you can have different types of conversations and I think people are willing to engage a lot more. You can relate to the things that you are seeing in a much more personal way."

Toogood, Burrill and Lamb create site-specific installations

Spread across the house's state floor and below-stairs level, each room hosts a different exhibitor. Next to each display is a passage of text written by the designer that explains why they think that craft is still relevant today.

Among them are three makers who were asked to create site-specific installations.

Displayed in the house's drawing room, British designer Max Lamb has created a 24-square-metre rug made up of interconnecting amoebic shapes.

The rug was made using 100 kilograms of leftover Yorkshire wool sourced from a local textile factory and dyed using natural materials that Lamb harvested himself from the Harewood estate.

Working with the estate's head gardener Trevor Nicholson, Lamb sourced materials such as oak and birch bark, alder cones, eucalyptus leaves and ivy berries to dye the wool. The wool was then tufted into rugs by Trendy Tuft of Cleckheaton in West Yorkshire.

"I am interested in serendipity and circumstance and how they affect any process," Lamb said. "These rugs would be completely different if I'd gathered the materials in a different week, month or season. We are too hung up on the idea of beauty as something that can be controlled. I can control the formula, but not the outcome. That, for me, is where the beauty lies."

Outside the house, Anthony Burrill has erected a four-metre-high Tyvek-wrapped scaffold tower that answers the exhibition's central question of why craft matters with the words: 'We are who we make', 'We are what we make,' 'We are when we make' and 'We are how we make' written on each of its four sides.

"It feels like a real moment," Burrill told Dezeen. "I've taken what I do and put it into a completely different environment. I like that this exhibition takes the work out of the graphic art world and presents it to a wider audience."

London designer Faye Toogood was tasked with filling the 76-foot gallery space that extends across the whole west end of the house. Toogood selected 30 pieces from her extensive archive of fashion, product and furniture design to display across a huge industrial steel shelving unit that ran the length of the space.

Each of the pieces in the showcase were made by a network of British craft people.

"There is a generosity in craftsmanship," said Toogood. "People in the craft community share their knowledge and expertise for the greater good. In times of increased automation, the skills and qualities of craft feel more valuable than ever."

Makers explain why craft matters

While the organisers only had budget to commission three makers to create new works, almost every maker tailored their product to suit the space.

Some exhibits were designed specifically for a certain spot within the house, while others were placed within a room that contrasts or connects to the nature of their work.

For example leather vases by Simon Hasan are displayed in the leather library while knives by Leszek Sikon forged from reclaimed steel cable are in the kitchen.

"We wanted the pieces to form a conversation with the interiors rather than a battle," explained Marriott.

Costa Rica-born Edinburgh-based designer Juli Bolaños-Durman is exhibiting a series of vessels made from glass in the house's bathroom. Inspired by her grandmother's collection of perfume bottles, each vessel is hand-cut from a mixture of found glass and blown glass rejects.

"I think of craft as a vehicle for intuitive play, and I like to create joyful pieces, giving old and discarded materials new life with new meaning," said Bolaños-Durman. "I believe that creating space for play, fun and humour is vital."

Other pieces were selected to sit in contrast to their surroundings, such as those by up-cycled furniture designer Yinka Ilori. The London designer's colourful 'If Chair's Could Talk' series was arranged in the centre of the House's silk-lined Cinnamon Drawing Room. It's surrounded by looking-glasses and portraits of the Lascelles family, for whom Harewood House was originally built and is still home to today.

Painted in bright colours and upholstered in clashing fabrics, the five chairs in the series are each inspired by a real-life character from Ilori's childhood growing up in London as the son of Nigerian immigrants.

"It's like the chairs are in conversation with the room," Ilori told Dezeen. "It's a contrast of narratives, colours and contexts. For me it reflects the diversity of cultures and heritages that we have in the UK."

Country houses should be places to engage, not just observe

Useful/Beautiful was originally intended to be a one-off show but has since become the first Harewood Biennial, with repeat craft and design exhibitions planned for the coming years.

Jane Marriott, who was formerly managing director of The Hepworth Wakefield, and prior to that director of development at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, was enlisted as director of Harewood House Trust in December 2016.

From the outset, she said that her goal was to reinvent the heritage property as a forum to engage rather than simply observe.

"Our dream is to be able to commission more makers and designers," she told Dezeen. "This time we've been able to do three, next time we'd like to perhaps do five. It's not so much about the quantity but more about establishing Harewood as a place for great contemporary exhibitions."

"There has been a shift in the country house and heritage sector," she continued. "More and more of these locations are transitioning from functioning like temples – places where you might go and admire or worship at the site of the object – to places where you can go to really engage in subjects and take part in a dialogue."

"Because it isn't a gallery, in some ways it's less intimidating than a gallery where you're almost expected to have some prior knowledge or understanding of what you're looking at. Here, in this kind of setting, it doesn't really matter."

Macdonald agreed: "It struck me that Harewood should be able to continue to evolve, and not be something that is simply admired from a distance. We wanted to create an exhibition that would help people get closer to the house and understand its many layers."

In 2017, Dezeen reported on how fairs exhibiting collectible design such as Nomad were leading the way by showcasing work in spectacular domestic settings. The inaugural edition of Nomad was held in a luxurious clifftop villa that was formerly owned by the late Karl Lagerfeld.

The format is a move away from traditional fairs like Design Miami and PAD where exhibitors show work in artificially lit booths inside tents and convention centres.

"It is the direction that fairs are going in," said Nathalie Assi, founder of London gallery Seeds, at the inaugural edition of Nomad. "Everybody is more relaxed, there is less attitude and the message is very clear. It's easy, and it maybe incites people to consider buying things they wouldn't have considered in other settings."