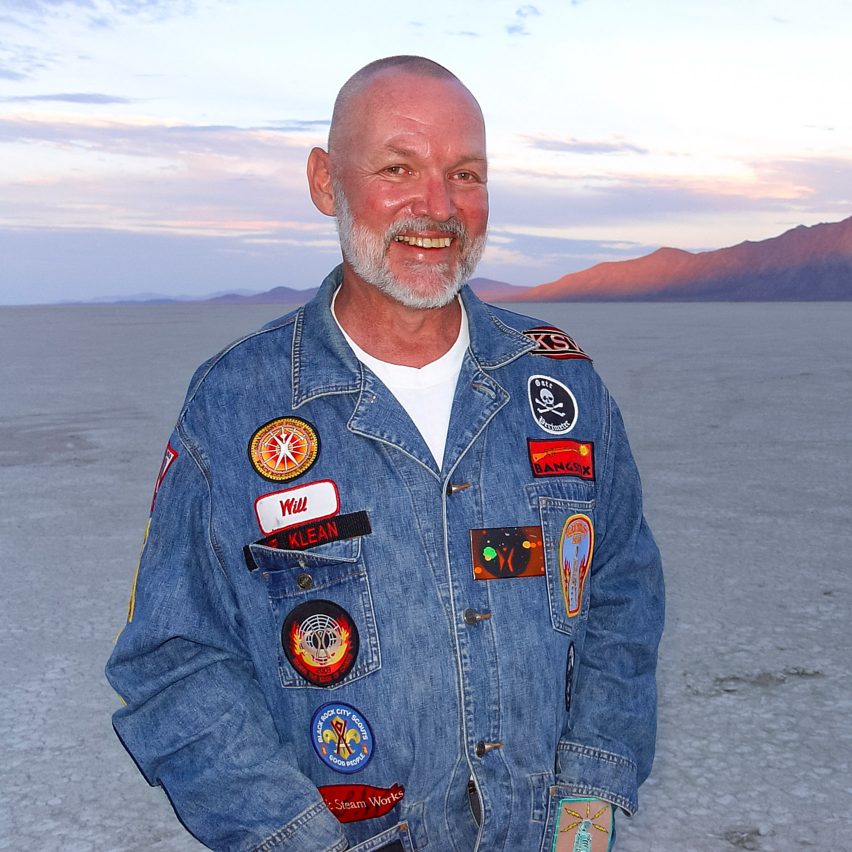

Black Rock City is designed to "sprout out of nothing", says Burning Man co-founder Will Roger

Burning Man co-founder Will Roger has spent the last 14 years capturing the festival in aerial photographs. As a book of his images is released, he spoke to Dezeen about how they created a pop-up city in the desert.

Compass of the Ephemeral: Aerial Photography of Black Rock City through the Lens of Will Roger, shows how the festival has grown from a small camp into a mini metropolis with a population of 70,000.

"If you look at the pictures in sequence from 2005 to 2018, the most significant thing that you see is that the city has grown in size," Roger told Dezeen.

Festival began on a San Francisco beach

The Burning Man festival was initially established by the late Larry Harvey, who previously spoke to Dezeen about how the festival had developed.

Harvey kickstarted the event as a campfire circle on a beach in San Francisco in 1986 before moving it to the desert in Nevada. The late architect and urban designer, Rod Garrett, was enlisted to oversee the city design.

Roger, who is cited alongside Harvey and Garrett as one of the festival's six founders, is credited with forming the Department of Public Works (DPW). This comprises a workforce of volunteers that build and deconstruct the pop-up site each year.

"I was put in charge of desert operations in 1997," Roger told Dezeen. "We began to develop a department that builds a city that sprouts out of nothing and then operates as a fully functioning city, with airport and hospitals and emergency services, and all kinds of camps and theme camps and interactive camps."

"And then a month later, it's completely gone," he continued. "We often talk about it as being the miracle in the desert."

A model for other temporary cities

The speed and efficiency of making Burning Man, which runs from 25 August to 2 September this year, has proved an important model for other similarly temporal developments, according to Roger.

"When you look at the way Black Rock City operates in the way it's built, and cleaned up, it applies to other locations where cities might be done in the same way," he said.

"We've been consultants with the military in designing temporary cities," he added.

"When there's several thousand firefighters working on a large forest fire or wildfire, they have to build a small encampment, and they've drawn on some of the ideas that we've built in Black Rock City."

Organisation of site visible from the air

Garrett's arrangement for the festival, that exists to this day, comprises campsites laid in a huge semi-circle around the "burning man" – a giant effigy set alight at the climax of festivities.

Roger adds that his photographs, taken from a plane, help to convey Garrett's organisation, which often isn't as apparent to those on the ground.

"When you're in the city, it seems a little bit chaotic," he said. "There's a lot of energy in the city, a lot of stuff going on."

"And then you get a mile above it, and it looks so orderly. It looks perfect."

Read on for full interview with Will Roger:

Eleanor Gibson: Can you tell me a bit about the book?

Will Roger: It's a book that has 14 years of my aerial photographs of Black Rock City. The book contains five essays that describe the different aspects of the Burning Man organisation and how we've developed over the years.

Eleanor Gibson: Can you describe the changes of the Burning Man festival that the book traces? How has the festival developed over the years?

Will Roger: Certainly the big thing is that the event has grown in size and population. If you look at the pictures and sequence from 2005 to 2018, the most significant thing that you see is that the city design has grown in size.

Eleanor Gibson: It's become very well known for its architectural installations and the way that it's a temporal city, can you tell me a bit about that and your involvement in that?

Will Roger: I was put in charge of desert operations in 1997. It was the only year we didn't hold the event on the Black Rock desert, we held it in the valley next to us.

The permit required that we have a city designed. And so I asked Rod Garrett, my good friend, to design the city for me, and he did that.

We formalised the building, the setup and the cleanup of how we operate in the desert in those early years.

We often talk about it as being the miracle in the desert

So actually 1997, 1998, 1999, we began to develop a department that basically builds a city that sprouts out of nothing, Black Rock desert, and then operates as a fully functioning city, with airport and hospitals and emergency services, and all kinds of camps and theme camps and interactive camps. And then a month later, it's completely gone.

We often talk about it as being the miracle in the desert. When you see it in that context, and you experience the building and the cleaning up of it, it's quite amazing.

Eleanor Gibson: Do you think there is something that architects and urban designers can learn from Burning Man?

Will Roger: Yeah, I do. Black Rock City, and Rod Garrett as a designer, have been studied by architects, and people in urban planning, and different sciences of city building and design.

It's an interesting thing that when you look at the way Black Rock city operates in the way it's built, and cleaned up, it applies to other locations where cities might be done in the same way.

We've been consultants with the military, in designing temporary cities and firefighters. When there's several thousand firefighters working on a large forest fire or wildfire, they have to build a small encampment, and they've drawn from some of the ideas that we've involved ourselves with and built in Black Rock City.

There's a creative experience in Black Rock City that's infectious. Even a non-artist will come to Burning Man and be stimulated to create things. I'm not sure how that translates to other temporary cities that might be built, but I think that it could be.

What's more important to me is that we get to experience humanity in a much more positive way than we do in normal culture, and that that's transformative. It transforms people's lives. That's what I take away from the Burning Man experience.

Rod Garrett designed the city with an emphasis on creating community

The city design itself is a very important part of that. Rod Garrett designed the city with an emphasis on creating community. I believe that the city design itself does that.

The other thing that does it is the place. We're in the high desert, it's the great basin desert, and the desert has the power of nature.

The stars at night are incredibly lucid and powerful. And I believe that that creates a connection to the earth that can be transformative. And then you're in a city where there's unconditional love, and people come with the attention of creation and making art. And that's a little bit different than what we call the default culture, the default world, which you're experiencing profoundly in New York City right now.

Eleanor Gibson: I was wondering if you could expand on that a little bit. You know, Burning Man is often kind of seen as this utopian city that people get to experience for just a short period of time. What are the features of it that make it so unique?

Will Roger: Well, one thing that is different, when you walk around New York City, you are bombarded with advertising, and consumerism.

At Burning Man, we don't allow vending, we don't allow money to be exchanged. We don't allow any kind of advertising. If you come in with a rental truck that says u-haul on it, we make you cover that up with brown paper so that nobody can see the advertising.

So for a little bit for a week, you really get no exposure to consumerism. And I think that that is actually more profound than people realise. Because again, our culture, in our normal default culture, consumerism and being a consumer and the idea that you can purchase happiness, I think that's pretty predominant. And at Burning Man, that's not there at all.

There's an old slogan that goes way back in our history, and it's called no spectators. So you don't go to burning that to watch someone else perform for you. You go to Burning Man to be the performer.

There is no consumerism at Burning Man

So the idea is that everyone's an artist, everyone's a performer. And we're all working together in the creation. And I think that that's a real important aspect of Burning Man.

Eleanor Gibson: You've spent a lot of time documenting the event. I was wondering, what have you learned? Are there any surprises that you found when you look back at your photography? Or what have you learned from that experience?

Will Roger: You know, growing up in a small terrain, over a beautiful city, like Burning Man is always a special experience.

I owe a lot of my photography work to the pilots that I work with, mostly to current pilot Dave Barrett. His nickname is Purple Haze. And he's a remarkable man, and a remarkable pilot. What I mostly take away from each year's experience of flying, is that how different the atmospheric conditions are.

Some years I'll go up, and it's windy and dusty, and I won't even be able to see the city. And I have to trust that my camera is recording something that I might be able to enhance later on digitally. And that's what I've done with a lot of the images.

The other thing that I think is profound for me, when you're in the city, it seems a little bit chaotic. There's a lot of energy in the city, a lot of stuff going on. And then you get a mile above it, and it looks so orderly. It looks perfect. I think that that comes out in my photographs.