Nicholas Grimshaw maintained his high-tech ideals for 50 years

We continue our high-tech architecture series with a profile of Nicholas Grimshaw, who has stayed true to his high-tech ideals over a career spanning more than 50 years.

Nicholas Grimshaw is the details man of high-tech architecture, a style that emerged in the 1960s and emphasises and celebrates structural and circulation elements.

His buildings tell the story of a man who loves engineering as much as architecture, an architect who is fanatical about the craft of construction. He looks the part too, with his signature round spectacles and floppy haircut.

Infrastructure has always been at the core of Grimshaw's practice. In train stations, factories and housing, he reveals the qualities he values most in architecture: functionality and flexibility.

"Buildings should have good bones and they should be reusable," he told Dezeen in a recent interview. As perhaps the most consistent of all the high-tech architects, he has carried this same message throughout his career.

Born in 1939, Grimshaw showed an interest in building from an early age, no doubt influenced by his family. He was raised in Guildford, in the south of England, by a mother and grandmother, who were both artists.

However his father, who died when Grimshaw was just two years old, had been an aeroplane engineer. Grimshaw also speaks fondly of two great grandfathers – one a civil engineer who built dams in Egypt, and the other a physician who was instrumental in bringing sewage systems to Dublin.

The architect recalls hours spent making structures out of Meccano and constructing treehouses with friends. He also developed a fascination with boats and the way that they were put together. "It was quite a constructive youth," he said in a BBC radio interview in 2003.

After dropping out of college at the age of 17, a visit to Scotland led the young Grimshaw to the Edinburgh College of Art, where he realised immediately that architecture was the career for him. From there he went on to the Architectural Association in London and graduated in 1965.

Grimshaw spent his first few 15 years of practice in a partnership with another celebrated British architect, Terry Farrell. They shared an office with Archigram, the gang of architectural radicals whose members included Grimshaw's former tutor, Peter Cook.

The influence of these experimentalists is evident in Grimshaw's first completed design, the now-demolished Service Tower for Student Housing in west London, affectionately know as the Bathroom Towers.

Completed in 1967, it was a spiral of fibreglass pods containing 30 bathrooms, accessible to around 250 students. It combined the kind of innovation that Archigram championed with a more rational practicality.

"We determined that a helical ramp with all the bathrooms on it was by far the most efficient way of doing it, because whatever floor you entered the ramp on, you could keep going round until you found a bathroom that was free," Grimshaw said.

The architect's other early projects include the Park Road Apartments, a pioneer of customisable housing, and the Herman Miller Factory, a building that could be completely reconfigured.

Both emphasised Grimshaw's belief that all good architecture should be adaptable. The architect detested what he now calls "handbag architecture", buildings that can only serve one purpose and are therefore likely to be only useful for a limited time. The Herman Miller Factory is currently being converted into a facility for Bath Spa University, which Grimshaw believes is further proof of his point.

"I've even suggested that when architects submit a building for planning permission they should be asked to suggest ways in which it can be used for alternative things in the future," he told Dezeen. "The more of that that goes on in the world, the better place the world will be."

Grimshaw and Farrell went their separate ways in 1980, in an apparently messy divorce – according to Design Museum director Deyan Sudjic, even their wives stopped speaking to each other.

Although both avoided commenting about it, the contrast in their thinking was clear for all to see in the years that followed. While Farrell plunged headfirst into flamboyant postmodernism, a far cry from the functionalism of high-tech, Grimshaw stayed true to his craft.

That's not to say his projects were without character. The Financial Times Printworks, completed in 1988, turned the process of printing newspapers into theatre, visible through a huge shop window. While the Sainsbury's supermarket in Camden, built the same year, was a heroic celebration of steel construction.

However Grimshaw's big break came with the commission for the International Terminal at London Waterloo station, the UK's new gateway to Europe.

Finished a year before the Channel Tunnel, it put a modern spin on the grand railway halls of the Victorian era. Its monumental arched roof was completed in transparent glass, with the structure exposed on the outside.

The building cemented the architect's reputation and elevated him to the world stage. It was lauded with the RIBA Building of the Year award (the predecessor to the Stirling Prize) and the European Prize for Architecture, better known as the Mies van der Rohe Award.

"People ask me what my most important project is and I would always say Waterloo, without a doubt," said Grimshaw.

Experimentation continued to underpin Grimshaw's practice in the lead up to the millennium.

With his design for the British pavilion at the Seville Expo of 1992, he employed a kit-of-parts approach to show how a building could be both easily demountable and energy efficient. In a factory for plastic bearings manufacturer Igus, he used tension structures, supported by towering yellow pylons, to create flexible column-free halls.

He even achieved his childhood dream of building a boat... almost. A rare private house project, Spine House, saw him suspend a wooden hull inside a glass shed in the German countryside.

Like fellow high-tech hero Norman Foster, Grimshaw idolises Buckminster Fuller, the American architect who popularised the geodesic dome. He had experimented with self-supporting domes during his studies at the AA, but is wasn't until the Eden Project, unveiled in 2001, that he was able to have a go at building a geodesic structure of his own.

Working with Anthony Hunt, the engineer behind many of high-tech's biggest triumphs including Hopkins House and the Reliance Controls factory, Grimshaw transformed a Cornish clay pit into an international attraction. Four giant domes interlink like soap bubbles, creating a climate-controlled environment for 5,000 varieties of plants.

Formed of hexagonal EFTE panels rather than glass, the biomes posed a challenge to build, not least because the topography of the seaside site was in contact flux. But the project proved so successful that it spawned replicas all over the world and Eden Project remains a Grimshaw client to this day.

"We designed the pillows so that they could be replaced," said Grimshaw, revealing that flexibility was still at the forefront of his thinking. "Over the years that the structure exists, more and more fascinating cladding systems might emerge and eventually it might actually grow its own skin," he suggested.

Around this time, Grimshaw's firm went though some big changes. Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners became simply Grimshaw, a partnership company with staff in the hundreds and offices in different continents, while its founder explored new avenues as the president of the Royal Academy of Arts, a role he held from 2004 to 2011. But the quality and consistency of the projects stayed largely the same.

The long-delayed Thermae Bath Spa showed how technology can be sensitive to history, while a series of transport infrastructure projects progressed the ideas first floated at Waterloo. Even projects of the most recent decade, from the Fulton Center in New York to Pulkovo Airport in St Petersburg, stand as symbols of progress and innovation.

There is of course one exception – the Cutty Sark restoration, which saw a historic tea clipper encased in glass, was torn to shreds by critics, and even won the Carbuncle Cup, an award bestowed on the UK's ugliest buildings.

Grimshaw stepped down from the helm of his firm in June 2019, but not before being awarded the Royal Gold Medal from the RIBA. The accolade had already been presented to Foster, Richard Rogers, Michael and Patty Hopkins, and Renzo Piano, all while high-tech was still in its heyday. By the time it came to Grimshaw, the world had moved on.

Even the architect was unsure about whether the term high-tech was still relevant – he claimed that he'd heard it used to describe everything from toasters to shoes.

But in his citation speech, he made people realise that the values that drove this style to success are more relevant now than ever before.

"My life, and that of the practice, has always been involved in experiment and in ideas, particularly around sustainability," he said. "I have always felt we should use the technology of the age we live in for the improvement of mankind."

Led by architects Foster, Rogers, Nicholas Grimshaw, Michael and Patty Hopkins and Renzo Piano, high-tech architecture was the last major style of the 20th century and one of its most influential.

Our high-tech series celebrates its architects and buildings ›

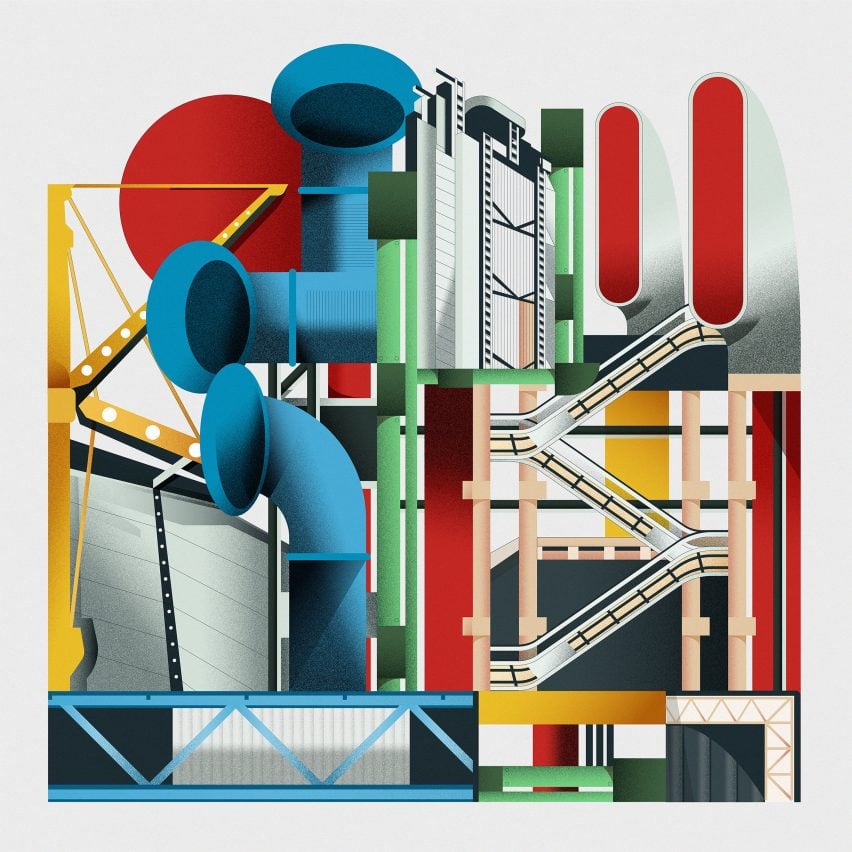

The main illustration is by Vesa Sammalisto and the additional illustration is by Jack Bedford.