"We were all broke" when we designed Park Road Apartments says Nicholas Grimshaw

British architect Nicholas Grimshaw explains the impact that limited resources had on the housing block he designed with Terry Farrell, in this exclusive video interview created for our high-tech architecture series.

Completed in 1970 by Farrell and Grimshaw Partnership – the architecture practice set up by the duo five years earlier – Park Road Apartments is an aluminium-clad residential tower that overlooks Regent's Park in London.

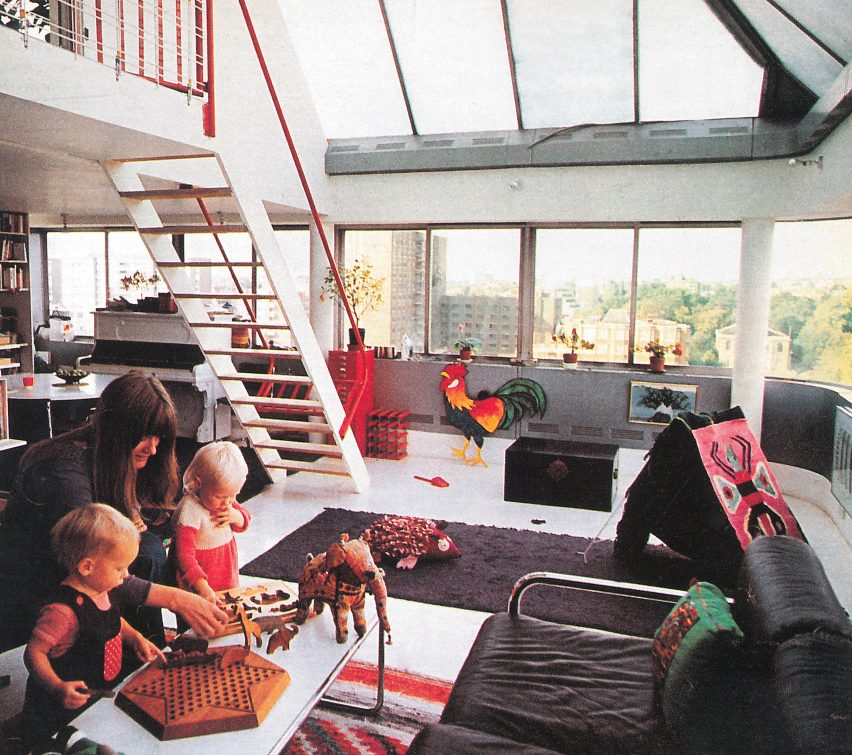

Forty flats are contained within the 10-storey building – including the former homes of Grimshaw and Farrell, who lived in the tower for several years with their young families.

The architects were both members of the Mercury Housing Society, a co-operative consisting of 40 friends and aspiring homeowners.

"Park Road was a co-ownership housing society and we thought the answer to life was to gather some kind of community," Grimshaw told Dezeen in the interview at his home.

Amongst the co-operative's members was also structural engineer Anthony Hunt, who worked on a number of seminal high-tech projects including Reliance Controls by Team 4 and Richard Rogers' Inmos Microprocessor Factory.

Park Road Apartments made history as the first co-housing scheme to procure a site in central London and was built with a limited budget.

"We were all broke," said Grimshaw. "And the idea was to build it as cheaply as you possibly could."

In order to keep the cost of the project down, the architects created a simple design and used materials in ways that were considered unconventional at the time.

"It was just a very, very simple concrete frame with slabs separated by round columns. I mean, it's almost like a children's toy really," said the architect.

"And with industrial corrugated aluminium on the outside, which was the shock because people didn't use aluminium for that sort of building."

The anodised aluminium skin that envelops the building at 125 Park Road owed its inexpensiveness to the speed and ease of its manufacturing.

"They make them by putting aluminium material between rollers, which have ridges in them, so that they basically come out in a wavy shape," explained Grimshaw.

"If you want to curve it just speed up one of the rollers and it comes out like that."

Slicing through the facade at each floor are ribbon windows, which wrap around the building to offer panoramic views of the neighbourhood. Similar to the cladding, mass production also helped to drive down the cost of the windows.

"We got a bus window manufacturer to make [the windows]. So we got a good price for them," said Grimshaw.

"[There was] the concrete, steel subframe, and the windows and the cladding. So four materials and that's it."

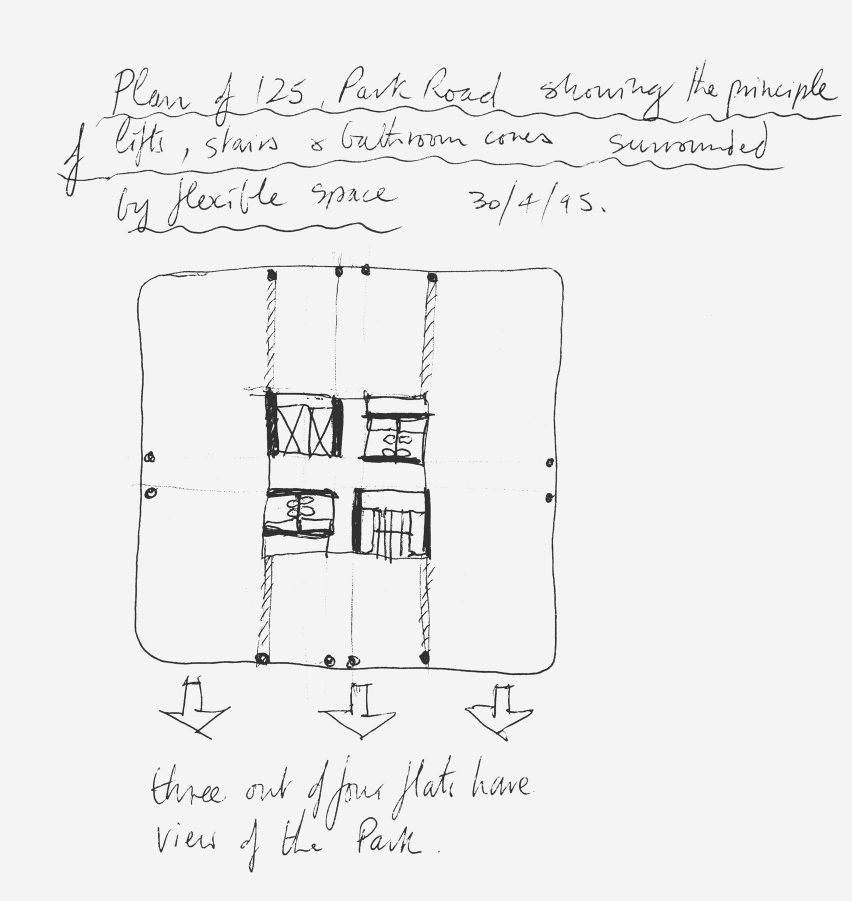

The structure of the building was also pared back, with non-structural internal walls considered superfluous and eliminated from the design.

Instead, Park Road Apartments is primarily supported by an office block-inspired central core – a first for a UK residential building.

In addition to optimising the budget, the central core also enabled the pair of architects to experiment with the internal configuration of the flats.

"We wanted to make a block of flats as flexible as possible," said Grimshaw. "And the basic idea behind that was that you leave the structure as stripped down as you could, so that you could have any layout and you wanted."

Each floor could function as one large apartment or could be arranged to accommodate up to 14 bedsits.

The tower, which received Grade II listed status in 2001, was originally received negatively by members of the public, due in part to it's ribbed-aluminium exterior.

"Once the building went up, everyone started noticing it," said Grimshaw. "And they basically thought it was totally inappropriate in that setting overlooking the park."

"A lot of taxi drivers called it The Biscuit Tin," he added.

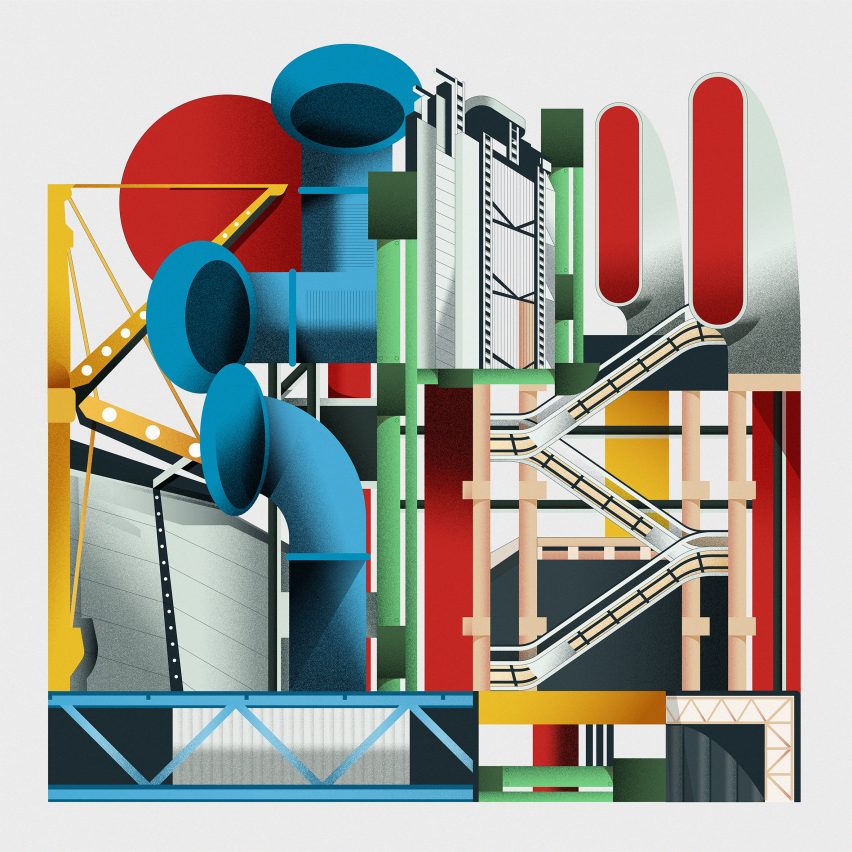

Through its use of industrial materials, its flexible interior and interrogation of the building envelope, Park Road demonstrated many features contingent with the architecture style that was later called high-tech.

"High-tech architecture – that expression, that title – sort of crept up on us really," Grimshaw said.

"It's quite difficult [to explain] because it's a sort of name that was cooked up after the event."

Buildings in the high-tech style helped to launch the careers of not only Grimshaw and Farrell, but also their contemporaries Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, and Patty and Michael Hopkins.

"I suppose a number of us started using new types of construction. And people started to notice that new materials were being infiltrated into their lives and they didn't quite know what was going on," said Grimshaw.

"But it was just architects searching for new materials, which people gradually pushed into a type – into a theme of design."

This movie was produced by Dezeen as part of our high-tech architecture series, and is the fourth video interview with notable high-tech architects.

It follows our video interviews with Norman Foster, who explained the challenges of designing the UK's first high-tech art gallery and how HSBC transformed his architecture firm into a global brand.

Emerging in Britain during the late 1960s, high-tech architecture was the last major style of the 20th century and one of its most influential. Characterised by buildings that combined the potential of structure and industrial technology, the movement was pioneered by Foster, Rogers, Grimshaw, Patty and Michael Hopkins and Piano.

Photographs are by Peter Cook, Hufton + Crow, Jo Reid and John Peck. Drawings are by Farrell and Grimshaw Partnership, and Nicholas Grimshaw. Images and footage are courtesy of Grimshaw. Illustration is by Jack Bedford.