"I don't want my pictures to tell people what they should think" says Alastair Philip Wiper

British photographer Alastair Philip Wiper explores all kinds of factories, from pork slaughterhouses to sex doll workshops. He says he isn't trying to shock or influence, just to show people where things come from.

Wiper photographs the facilities that make mass production possible. His images show the machines, the people and the processes used to manufacture the objects of our modern society.

But the Copenhagen-based photographer's aim is not to tell people what is right or wrong. He simply wants to reveal a world that the vast majority of people never see, so that they can understand it better.

"I don't want my pictures to tell people what they should think and how they should feel," he told Dezeen.

"I just want them to look and have their own thoughts."

Scale of consumption

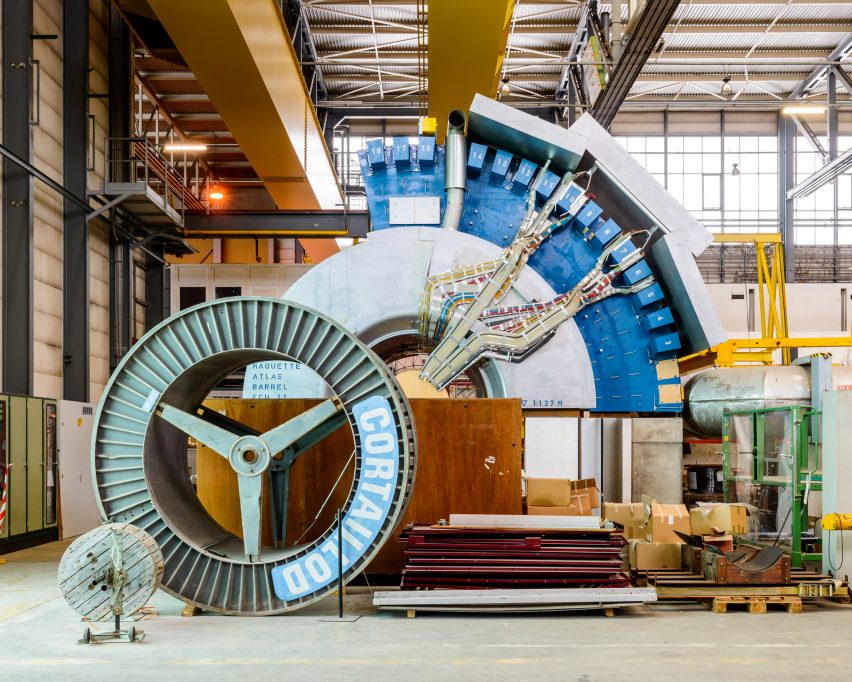

In his new book, Unintended Beauty, Wiper shares images from the factories of Adidas, Playmobil, Bang & Olufsen and more. He also shows power stations and scientific research facilities, along with a dairy farm and a cannabis greenhouse.

The venues he selects tend to be provocative, for instance, the Danish Crown slaughterhouse in Horsens. Wiper prompted an outcry from Dezeen readers after visiting this pork factory, with many shocked by the graphic nature of his photos.

What was more shocking, according to Wiper, was not the process itself but the scale on which it took place. By revealing it, he hoped to make people think about where their food comes from.

"The overwhelming feeling that I come away with, that is constantly going on in my head, is whether we need this much stuff. Do we need this many shoes or this much pork?" he said.

"The world has been ramped up to a point where everybody thought that this 'more, more, more' was good, and suddenly we're realising we don't need it."

Products of our imagination

Wiper says that, even though he has explored factories all around the world, he often encounters things he has never seen before.

On a recent visit to a condom-making facility in Denmark, he was stunned to find it in the back of a cheese factory. He also discovered handmade machines built several decades ago, still in good working order.

These places tell a story of human ingenuity that may be unfamiliar to people used to city life, claims Wiper, but which is fundamental to the world we live in.

"These places are all products of our imagination," he said. They're representing what we want and what we can do as human beings. Even when there aren't people in the pictures, they're all the products of our minds."

"There is a lot of humanity in that for me," he added.

"How do we get people to think differently?"

The photographer tries not to form opinions of the places or companies he visits.

While he wants to people to recognise the impact of consumption, he is also concerned about the infrastructures that depend on these factories. Not only are they making the objects we buy, they also provide jobs to entire towns.

"There are parts of the world that were once very poor, but now have a much better quality of life because of these factories," he added.

"Yes, the overall impact is something that we have to reduce. How do we do that without impacting these communities? How do we get people to think differently about the way that they consume? These are such complicated questions."

Unintended Beauty is published by Hatje Cantz. Wiper's photographs are also on show at the RIBA in London, as part of the exhibition Forms of Industry, open until 16 May 2020.

Read on for the interview in full:

Amy Frearson: How did you end up in this niche area of photography?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I studied philosophy and politics at university, but when I finished I had no idea what to do with my life. I met a Danish girl, moved to Denmark, and got a job in a restaurant, but I didn't want to be a cook. Then I started to make some T-shirts, just for fun, and taught myself to use Illustrator, which helped me I get a job as a graphic designer. I was working for an artist and fashion designer who also didn't have a in-house photographer so then I started taking pictures too. I taught myself and fell into it.

I decided I wanted to become a photographer, but I didn't want to be a fashion photographer or a portrait photographer. It felt very repetitive. Then I saw some work by some older photographers work in the 50s and 60s. In particular, Wolfgang Sievers and Maurice Broomfield, who were photographing big oil refineries. This was totally fascinating to me. I could see myself going to see the most amazing things, shapes and graphics.

You've got to be really fascinated by the thing you're working with

I went into this niche of industry and science, and pretty quickly I learned that the things I was experiencing and seeing were more important than getting a pay cheque. I think that's the key to photography or any job really; if you want to do it really well, you've got to be really fascinated by the thing you're working with. I wasn't interested in science or art particularly, but it can be nice to come at these things with a new energy. You look at everything with different eyes compared to somebody that has been in that world their whole life.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me about some of your first experiences of photographing factories and infrastructure?

Alastair Philip Wiper: There are two that stand out. One of them is the Odeillo Solar Furnace. In the beginning I didn't know how to get in anywhere, so I had to find places where I could just turn up. I saw a picture of this building online in an article called "the 10 strangest buildings in the world" or something like that. I camped outside for two days, just watching the light changing on the mirrors. It was a kind of pilgrimage.

Then there is CERN, which is a place I've been back to three or four times. The first time I booked myself on a public tour, where you don't see anything. So I asked the PR office to show me more, and they put me on a trip with an engineer to see some real things. That was a lucky break. I don't know if they would do that these days.

Amy Frearson: I presume getting access to these places is the biggest challenge?

Alastair Philip Wiper: After I got into CERN, I had a couple of other lucky breaks so that suddenly I had a portfolio that was starting to show that I could get inside places. But getting access is always the hardest, especially in the beginning. I have to talk my way in. These days I know the job position of the person I need to find, but in the beginning I had no idea. I thought a caretaker might sometimes let me in the back door, but that never happened.

Amy Frearson: One of your best-known photography series shows inside of the Danish Crown pork slaughterhouse in Horsens. It had a huge reaction from Dezeen readers. Why did you choose to photograph this type of factory?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I do a lot of self-initiated projects and I'm always looking around, thinking about the everyday objects that I consume. I want to know what factory they come from and how I can get in there.

Pork was an obvious one because I live in Denmark, and there's a lot of pork consumed in Denmark and exported as well. I'm very interested in these kind of taboo subjects. I like things when things we interact with physically are a little bit controversial, when they have a macabre side or a dark humour. I maybe wasn't thinking about that before I went but after I came out there was something dark about the whole thing that I just found attractive.

At the time I was quite into eating meat. I had been vegetarian when I was a teenager but I stopped because I really enjoyed food. My love of cooking and eating became more important to me than being vegetarian. But it made me feel like I needed to understand what I was eating and where it came from.

Amy Frearson: Did the experience shock you?

Alastair Philip Wiper: The process of seeing pigs going in and being slaughtered wasn't particularly shocking, because of course I knew what needed to happen to get the bacon to my table and I felt quite strongly that people that ate meat should understand this. If you're going to eat meat, you should be comfortable with that process and if you're not comfortable then you probably shouldn't eat meat.

If you're going to eat meat, you should be comfortable with that process

The shocking thing for me about the slaughterhouse wasn't that pigs go in there and get killed, that they have their guts taken out, chopped up and sold to be eaten. That wasn't shocking to me. It was the volume, the scale, which was amazing.

I don't want my pictures to tell people what they should think and how they should feel. I just want them to look and have their own thoughts.

Since then my attitude has changed a little, in that I've become more aware of the impact of meat on the environment. I didn't think we needed to be eating as much meat. I still enjoy meat but I eat less meat. I only have it on special occasions.

For me the question is, do we need to consume as much? I think you can say that about pretty much everything we consume. As long as there's a demand for it, there's going to be places that are killing hundreds of thousands of pigs a week.

Amy Frearson: What other things shock or surprise you in the spaces you photograph?

Alastair Philip Wiper: When I first started going to these places, every place was incredible. I really liked seeing tangles of pipes and wires, that kind of thing. I need to see a really good tangle of pipes and wires to be impressed these days! But I still get really happy when I see things I haven't seen before. I've seen a lot of places and I find similarities in all of them, but I also see things that I've never seen before pretty regularly.

Recently I was at a condom factory in the countryside in Denmark. I had been been looking for a condom factory to photograph and thought I would have to go to Germany, but a friend told me there was a condom factory in Denmark. I asked them if I could come and photograph it and they said yes, sure, but told me it wasn't very big and it was very old.

It turned out to be a small room in a corner of a cheese factory. The cheese factory was owned by a company that has a few businesses, that buys businesses when they can see that there's good value in it, no matter what it is. The condom factory had actually existed since the 1950s I think and the machines were homemade. At the time they had asked their engineer for a solution for condom packing, so he built one out of wood and put a motor on it. It still works and that's probably the reason that this company is still profitable. If that machine broke, they would have to buy a new one and then suddenly, maybe it's not worth it. This is pure conjecture, but this is how my imagination works.

They also had machines that blow up condoms, to test how much air can go in there, and a machine that is like a dildo, that takes it on and off hundreds of thousands to see if it breaks.

Most of the time I see people that are happy, just living a different life to the one that I do

I love the contrast between CERN, where the greatest minds in the world are trying to answer the biggest questions of the universe, the greatest machines human beings have ever seen, and then in my backyard I can find a condom factory that is equally as fascinating.

Amy Frearson: Do you think people are generally unaware that so much construction and industry goes on in the countryside? Is that something you hope to reveal in your pictures?

Alastair Philip Wiper: It's not something I've thought about that much. I don't differentiate between the countryside and the city. But of course I'm in factories a lot and the world I come from doesn't see what happens in these places. While I feel like there is a big split between the communities that live in these towns and our cosmopolitan, big-city life, I don't think I have ever seen anything terrible or been to a factory where people seem unhappy.

People that live in our world have this assumption that it's horrible work and a horrible life in these places, but most of the time I see people that are happy, just living a different life to the one that I do. But it's definitely a world that I wouldn't get to see if I didn't go to visit these places.

Amy Frearson: Have you ever photographed anywhere that made you think differently about a product you consume?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I'm not an investigative journalist or photographer. I'm not trying to show the good or bad side of these places, and I'm usually doing it with the approval of the company that owns the factory. I'm not trying to uncover things. It is also really hard to go into a place for a day and come away with a valid opinion of what is right and wrong. There can be things that are maybe a little bit shocking to us, when actually there's nothing wrong with them, or there can be things that look totally fine, but actually are really bad. I try to be careful when I form opinions, but it's not really what I'm trying to do.

The overwhelming feeling that I come away with, that is constantly going on in my head, is whether we need this much stuff. Do we need this many shoes or this much pork? The world has been ramped up to a point where everybody thought that this 'more, more, more' was good, and suddenly we're realising we don't need it. But communities are surviving on these factories. There are parts of the world that were once very poor, but now have a much better quality of life because of these factories. Yes, the overall impact is something that we have to reduce. How do we do that without impacting these communities? How do we get people to think differently about the way that they consume?

I hope that anybody would find it interesting to see the way that things are made

These are such complicated questions. I'm confused, I don't know. Maybe that's why I'm trying not to say anything with my pictures, to tell people how to think. It's a discussion they can have with themselves. I'm thinking everyday about the way I consume, and how that impacts the world, in a way that I didn't three years ago. It's going to take a while to trickle down to everybody, but hopefully it will happen.

Amy Frearson: With your work now on show at the RIBA, do you think there are lessons for architects in your pictures?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I hope there is, but to be honest I know very little about architecture. I hope that anybody would find it interesting to see the way that things are made. Throughout history people have found creative inspiration through things that are made for practical purposes. I don't think I'm doing anything new there.

Amy Frearson: Can you tell me more about the technical side of your process? What is your process of shooting and editing, and what equipment do you use?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I use a DSLR camera mostly. I shoot medium format sometimes, but I can't always afford to shoot on medium format, because I need to work super fast and I beat my equipment up a lot. Normally I work very quickly, so I drop lenses and cameras! My most important tools, apart from the camera, are my tripod and wireless shutter release.

I don't edit a lot. I try to give the pictures my look, by playing with the contrast and the colour, and I adjust the perspective, I don't have any problem with removing something in the picture that I don't like, like a bin, but I don't do that very often, unless I need to. I try to keep everything as simple as possible. The less decisions I have to make, the better. If I do something, it's only because I think it's going to add to the picture. It's not for the sake of doing it.

Amy Frearson: When you say you give the pictures 'your look', how would you describe that look?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I want to have a lot of clarity. It shouldn't feel like it has a filter or a colour cast, it should be very neutral in tone and as sharp as I can get it. It should also be very colourful and bright. I don't want to make unsaturated, subtle pictures, I want them to be bold, colourful and in your face.

Amy Frearson: Does your approach change when you're shooting for a commercial client, rather than just for yourself?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I never really change the way I shoot. I approach every subject in exactly the same way and I am very rarely asked to do anything else. I feel really lucky to have that.

Amy Frearson: How important is it to you to show the people that work in these factories, as well as the machinery and objects?

Alastair Philip Wiper: I think this subject can become a bit too clean, too cold, too paralysed. I want there to be to be humour and passion in there, because these places are all products of our imagination. They're representing what we want and what we can do as human beings. Even when there aren't people in the pictures, they're all the products of our minds. There is a lot of humanity in that for me. That's why I want the pictures to be bold and colourful and a little bit dirty. They don't have to be too permanent and clean. There are interesting stories in all of these places.

Stories, humanity, humour and eccentricity are all my inspirations for doing this. I'm just blown away that people make all this stuff, that they build machines to build machines. It's crazy.