Lisbon's MAAT museum premieres documentary about SO-IL's temporary work with VDF

In this exclusive movie premiere screened as part of VDF's collaboration with MAAT, Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu of SO-IL explain 12 temporary architecture projects that feature in an exhibition at the Lisbon museum.

Made by Corinne van der Borch and Tom Piper, the video explores each project through movie footage, models and renderings plus interviews with SO-IL co-founders Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu.

It also features interviews with the Brookly-based architects' clients and collaborators.

The projects were due to feature in an exhibition called Currents – Temporary Architectures by SO-IL, which was scheduled to open at Lisbon's Museum of Architecture, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) on 27 March.

However, both exhibition and SO-IL's temporary Beeline installation remain shuttered until further notice due to coronavirus, so MAAT executive director Beatrice Leanza has instead teamed up with VDF for a virtual launch.

SO-IL's collaboration with MAAT was created with the support of Portuguese cultural organisation Artworks.

Currents exhibition features 12 temporary projects

Poledance, the first project featured in the movie, was an outdoor interactive environment constructed at MoMA PS1 in New York City in 2010. The video features an interview with Barry Bergdoll, was Philip Johnson chief curator of architecture and design, MoMA from 2007 to 2013.

Blueprint, the second project, involved shrink wrapping the facade of New York's Storefront for Art and Architecture in 2015. Eva Franch i Gilabert, director of Storefront from 2010 to 2018, explains the commission.

Next comes Pollination in Chengdu, China, 2011, followed by Transhistoria, a project for New York's Guggenheim Museum that took place at Jackson Heights in Queens, NYC in 2012. David van der Leer, director of the architecture and urban studies programme at the Guggenheim Museum from 2008 to 2013, explains the project.

Video features interviews with curators and clients

Matthew Slotover, co-founder of art fair Frieze, explains SO-IL's design of the snaking tent built for Frieze New York in 2012 and 2013, while Mark Lee, curator of the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial, talks about the Passage installation created for the biennale.

Lee also discusses L'Air Pour L'Air, SO-IL's performance piece for the 2017 edition of the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

The final three projects featured are Tricolonnade in Shenzhen, China in 2011, the Breathe installation for MINI Living in Milan in 2017, and Into the Hedge, a 2019 installation at Eero Saarinen's 1957 Miller House in Columbus, Indiana. Anne Surak, artistic director at Exhibit Columbus, discusses this last project.

Below is the transcript of the video:

Florian Idenburg: The idea of time obviously is really important. And designing time into the project is really important as well, because it doesn't mean that the project is done at the date it opens. There's no necessarily beginning or end.

Jing Liu: All architecture is temporary. It should remain and it would always remain open-ended. That is something we always try to remind ourselves in the design process.

Mark Lee: I always think SO-IL's work had that type of aura, this invisible envelope that projects out and sometimes this envelope was not that invisible. You know, like in the Korean gallery [Kukje Gallery, 2012], like in the temporary installations, it's always an aura. I'm very interested in this part of the aura of their work.

Florian Idenburg: Why we are working on temporary projects is that it allows us to very quickly respond also to new ideas and things we're curious about. Architecture can be a very slow profession. And sometimes, you know, the thoughts that you had at the beginning, you know, when the project is realized, you're already somewhere else with your thinking. The nice thing of the temporary works is, you know, very quickly, you can be sort of in dialogue with the contemporary world.

Poledance, New York, USA, 2010

Florian Idenburg: After the financial crisis, the economy collapsed, the environment collapsed. And so for us, it was really interesting to think of the idea of modernity through this system of the structural grid, in a way when it is weak, when it can always collapse, and one in which the visitor or the audience or the user is actually responsible for its stability.

Barry Bergdoll: We got a gridded field of unstable rods connected to a net above as though somebody had decomposed a volleyball net from a beach in Queens. It was almost a renewal in our faith in the program. Everyone was flabbergasted this was something that we hadn't seen yet, in the 10 year history of the competition.

Jing Liu: The American champions of pole dancing has called us and said, they want to do a performance in the space. It was the perfect collaboration, the space that was performative and the people occupying it was performative.

Florian Idenburg: That idea of a design process in which we are open to collaborations and partners and input from outside: that was, I think, one of the most formative, you know, aspects of that project.

Barry Bergdoll: Those themes in Poledance have found their way into designs for museums that are proposed and built around the world. So there's a very direct relationship between the experimental temporary installation and an emerging design practice establishing the themes of what they think are important in architecture.

Blueprint, New York, USA, 2015

Eva Franch i Gilabert: What SO-IL did with Florian and Jin did was to transform this space into, into almost like a pause, to make us reflect and think about issues of shape and form, but also security and insecurity, issues of permeability and access.

Florian Idenburg: We really love the idea of the Storefront being open. So we thought, how can we keep the Storefront open in the middle of the winter? We thought, what if we winterize the storefront?

Eva Franch i Gilabert: It was shrinkwrap for boats.

Jing Liu: Typically, when you shrink-wrap and the object that's inactive, it becomes this very static thing that's just sitting there. But then when you shrink-wrap a building where people are in there and then there is the conversations happening and the lights are spinning out of it, then it's a completely different reading of that object.

Florian Idenburg: This idea of agitating the audience and sort of rubbing up to the public sphere, also here to the public rubbed back because the next day the whole thing was sprayed over by graffiti.

Eva Franch i Gilabert: "Vandalized" would be a term that some people would use. "Occupied" could be another word. "Animated". "Enacted". And what I think is very interesting about their work is that the forms and even the shapes that they actually produce are not always immediately legible. They produce a moment of uncanniness: you don't know exactly what it is.

And I think it is in that moment of non-recognition in which there is kind of latent potency, of actually things becoming something else. It is in the making of otherness that I think we can identify and produce new spaces of action. So from a very specific space, that is the one of aesthetics, I think, as architects, they're able to produce spaces that also make us think and reflect about what the city can be, and what architecture can be.

Pollination, Chengdu, China, 2011

Jing Liu: Chengdu at that moment, was the fastest-growing urban site in China, and our installation was an attempt to address some of the consequences of a very fast-growing, urbanizing environment.

Florian Idenburg: And Chengdu is known as the Garden City.

Jing Liu: The famous Garden City that's been paved by concrete. We've invited the visitors to rent the bicycle and each bicycle will have seed bombs. This actually allowed many of the seed bombs to go into sites that are forbidden to the general public.

Florian Idenburg: After they dropped these bombs, they could geotag them and write a little note and it would show up on a map.

Jing Liu: It was important that the garden was forming in the imagination through this digital mirroring of the action itself. We are always interested in dematerializing and understanding time as a material to work with in our architecture.

Florian Idenburg: Specifically with this project. It's more about sort of the way in which you organize people in the city and have them participate in an experience. So how to create a way to escape the city while being in the city. We thought through storytelling we could create this isolation and we could sort of, you know, take you out of the loudness of the city into this other space.

Jing Liu: Every immigrant that comes with also the memory of the spaces they grew up in, the space that they passed through getting here, and that they also perceive of space in different ways.

Transhistoria, New York, USA, 2012

Florian Idenburg: Jackson Heights is one of the most diverse neighborhoods in New York, I forgot... 120...

Jing Liu: 173 languages spoken.

Florian Idenburg: So that's where also the title of Transhistoria comes from. It's like this idea of going through a transitionary moment in one's life and finding home.

David van der Leer: You would believe listening to these very intimate stories on these wonderful installations designed by SO-IL sitting in these very random spaces in Jackson Heights: somebody's apartment, a front yard for a church. And the experience of going through that as a visitor, I think must have been rather amazing.

Florian Idenburg: It was a very emotional project. And it was only there for two, I think, weekends or three weekends, and then it was gone.

Jing Liu: It was a really interesting and important platform for us to explore this concept of the space not only in what you can see, but also the invisible space.

Frieze Art Fair, New York City, USA, 2012

Jing Liu: How do we make a forgotten space in Manhattan to come into the public imagination with something that's very mundane and very ordinary?

Matthew Slotover: They asked us: can the tent curve? And, initially, we said no, this is what it is. And they said, well, let's ask the contractor. So we asked the contractor and they said: well, we could do that. So we have a tent that curves. It means you don't see the whole length at once, which makes it much less intimidating to visit. Looking straight forward, you don't see just the corridor, you see art. There are points where it curves and your eyeline hits an artwork. So it's a great end-of-corridor kind of moment, to see a picture.

Jing Liu: It is possible to create something extraordinary out of something that's incredibly ordinary. And that's the most enjoyable part of architectural design for us.

Matthew Slotover: It must be one of the lowest costs per square metre of anything that they've done because it's 20,000 square meters at a very small budget and it's only on for five days. So it's probably the shortest period and the largest thing.

Passage, Chicago, USA, 2015

Mark Lee: The space that's always used for transition, no one will even pay attention to that space, they did this big cathedral-like structure that makes people want to stay and ponder. And for them to do that installation and ingratiate it and slow people down as they walked through, make them aware, you know, of what was not there. And even for people that have been working there for decades. You know, just to stop and understand. I think that this is what architecture does best.

Florian Idenburg: We hoped that people passing over this ramp actually started to really become aware of their own body and moving through space; just contemplate that bodily movement.

Mark Lee: Where the passage was meant to be temporary, the fastening of the materials was quite easy. But the staging, you know, putting up the scaffolding in mid air was not easy. So, as a result, the dismantling of a project would be incredibly expensive. You know, it's almost like building the structure itself. So by default, it was grandfathered into a permanent piece. I think that's the brilliance of how they plan ahead.

In Bloom, Amsterdam, NL, 2010

Florian Idenburg: In Bloom was a project that was so temporary that it never even happened. We were asked by Ben Kinmont, an artist, to work on an installation together. And he is very interested in bringing people together also through events and ceremonies and rites.

Jing Liu: It was an object but at the same time is also a situation. So the architecture was a facilitator for an event and a relationship to happen. But it also had a form to it that was very recognizable and it became the symbol of that event, which is also what architecture can do very well. it solidifies and gives importance to often things that are transient and forgotten and invisible, and it makes those things visible.

Spiky, Beijing, China, 2013

Jing Liu: What's interesting about the canopy as an obsession for us is that we feel that in architecture we tend to ask very complex and complicated questions and not enough of the simple questions. For example, what it means to be under something. The question of the primitive hut: what it means to create an environment that was human and how do we re-examine that question of inhabiting, not just nature in such a direct way, but in a mediated way and make something that's easily deployable. And also it's about working with the light in this very transient way.

Florian Idenburg: And the creation of a canopy certainly also affects a lot of our other thinking, I think the space right above us, the relationship between us and say, the heavens and how to filter that layer is something that you know, you see in projects like UC Davis [University of California at Davis], or in our proposal for the Adelaide Contemporary or in some of these other more permanent institutional spaces.

L'Air Pour L'Air, Chicago, USA, 2017

Mark Lee: We invited SO-IL to collaborate together with the artist Ana Prvački.

Florian Idenburg: Probably the most intimate space in a way is literally the space one needs to be; just around you. So is it a piece of cloth? Is it a tent? Is it a shelter? What is it? It's like right on the edge of architecture,

Mark Lee: It's a performance piece, you know, so it has a really temporary setting and it's both a sound performance as well as an environmental performance. Talk about the air filter, which these structures are made out of, and how this breathing of these wind instruments you know, kind of facilitate the symbolic idea of the exchange of air between the plants and the human inhabitants.

Florian Idenburg: We worked together with a composer, Veronika Krausas. She wrote a piece which is performed by instruments that need air in order to produce music.

Mark Lee: You know, you go there you have a certain quietness of observation and studying the plants and suddenly there'll be these trombones and trumpet players, you know, and then maybe those who don't understand the environmental story behind it, but I think the performance became a window for the general public to understand the deeper message.

Tricolonnade, Shenzhen, China, 2011

Florian Idenburg: We are part of a continuous flow of architectural culture.

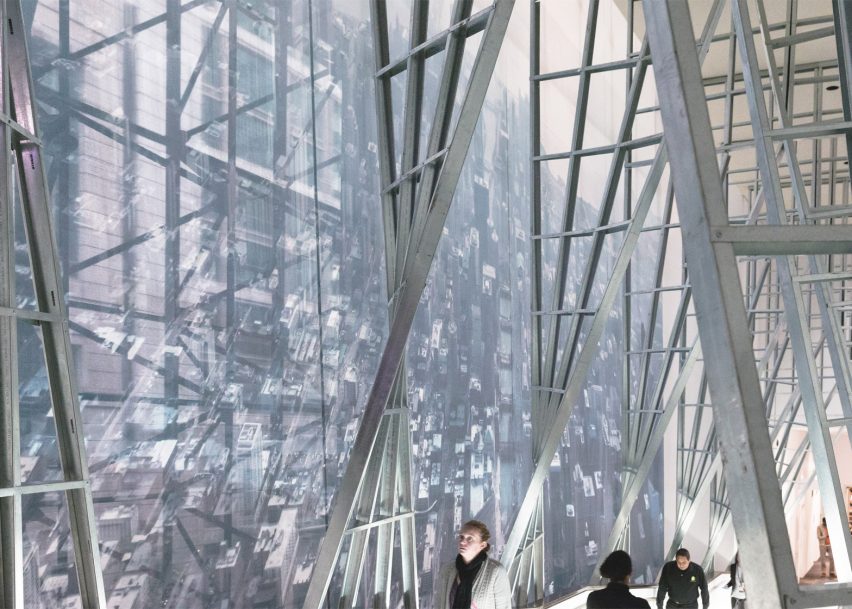

Jing Liu: By replicating and mirroring that one surface, that entire environment becomes this marble forest and this endless marbleized space that you walk into. Although it's only created by something that's very two dimensional and very thin.

Florian Idenburg: You see people enter and you don't know where they exit. It's a quite simple installation but I think spatially really rich. It does sort of riff on this traditional idea of the colonnade. Once you get into the space some people call it like digital space; it's almost like an infinity. And I think that relationship between something that's maybe, from the outside, typologically very historical, but as soon as you enter, you're sort of in a spatial dimension that maybe is a completely new type of experience.

Breathe, Milan, Italy, 2017

Jing Liu: In order to consume, we're producing a lot of things, but actually living can be very minimal. We were interested in doing more with less. And this situation that we created that we were imagining would be quite a dense living situation with very minimal material means to achieve that.

Florian Idenburg: To think about a new type of living, basically a MINI Living, so small footprint, more mobile, more flexible and more in relation to the environment. So it's a concept home but it asks basically can a home also be part of creating a healthy environment. I think what's also nice about this project is that it ties into some of our other projects that deal with wrapping and skins; it creates a completely new object. It's a new way of living and it also looks like a new way of living.

Into the Hedge, Columbus, USA, 2019

Jing Liu: Into the Hedge is re-examining some of the modernist ideas with a fresh eye. What if we make our project about purchasing and replanting the hedge that needs to be replaced in the Miller House?

Anne Surak: In this moment in history, we had this opportunity to see these trees as individual elements and to come into contact with them not as a border and a boundary but as a place that you can walk into and engage with.

Florian Idenburg: The installation in some way works with the landscape and the interior elements of the house and brings them into a new public experience.

Anne Surak: It was sort of the best of both worlds. It was a temporary project that was engaging to the community. And then it also went to good use and purpose within the community afterwards. And so people could understand in a tangible way, the way that things could transform over time. And that the temporary can also have permanent influence.

The whole project is really a progressive preservation effort. We want to build a community of people that cares about and understands the cultural heritage and legacy of Columbus. So when the time comes, people understand why we need to care for these things.

Jing Liu: And so understanding architecture not as the end of things, but as just a momentary coming together, of ideas, of materials and also pregnant with new possibilities as a different understanding of architecture.

Mark Lee: I think in the past people thought about temporary structures as an intermediate step to the permanent building. And I think in many ways, a lot of architects – I would consider SO-IL one of them – they see the temporary pieces as sometimes the final piece itself, you know. It's there for a short period of time, but it activated the life that we need it to.

Eva Franch i Gilabert: Sometimes we forget for whom it is that we are actually building, experimenting, testing the ground. And I think it's important that we reflect and really start somehow being a bit more aware about agency and about the politics of those aesthetics. In fact, I think this show is not only about temporary architecture; it's about how does one push the agenda and how does one take some risks and what can that afford us.