Architecture highlights from West Africa include projects from Cabo Verde to Burkina Faso

In the second part of our collaboration with Dom Publishers, the editors of the Sub-Saharan Africa Architectural Guide pick their highlights from countries along Africa's Atlantic coast and western Saharha.

With contributions from nearly 350 authors, the Sub-Saharan Africa Architectural Guide aims to be a comprehensive guide to architecture in the southern part of the continent.

The second volume of the seven-volume publication is named Western Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Sahel and focuses on the architecture of Cabo Verde, Burkina Faso, Mauritania, Mali, The Gambia, Senegal and Niger.

Read on for the book's editors, Philipp Meuser and Adil Dalbai's, picks from the region:

Cape Verde

Fogo Natural Park Headquarters, Fogo Island by OTO Arquitectos

The Fogo Natural Park project arose from the need to consolidate the protected area around the foot of the volcano Pico de Fogo.

OTO Arquitectos' adopted design strategy was to integrate the building within the volcanic landscape in an open dialogue with local materials and plants.

The use of dark materials ties the building to the landscape of lava, and the incorporation of ramps connects it to the ground and cover, merging exterior and interior spaces and creating a continuity of dark surfaces and shapes. The project won the National Prize of Architecture in 2013, but only seven months after it was built, the volcano erupted, burying it in lava.

Burkina Faso

Centre de Santé et de Promotion Sociale, Laongo, by Kéré Architecture

The centre consists of three units, organised around a central reception area: dentistry, gynaecology and obstetrics, and general medicine. The health facility is rendered with examination rooms, in-patient wards and staff offices. Special consideration is taken for visitors and families of patients with several shaded courtyards for gathering and waiting.

The playful window design emerged from the varying vantage points of standing, sitting, or bedridden individuals. Each of these picture frame windows focuses on a unique part of the landscape.

In keeping with the material aesthetic and ecology, local clay and laterite stone were used in the double-envelope construction of the walls for extra rain protection. The wood from local eucalyptus trees is used to line the suspended ceilings and covered walkways of the centre.

Mauritania

Grand National Hospital of Mauritania, Nouakchott, by Atelier de Montrouge

Built in 1966, the Grand National Hospital – an imposing structure at the heart of a large estate that has gradually come to accommodate several other new hospital facilities – is an archetype of post-independence architecture in Mauritania.

The country's only hospital for a long time, it suffered from a lack of maintenance of and appreciation for its imposing gesture. A change of status in the mid-1980s made it an independent public institution, resulting in an enhanced image of the building and integration into its immediate surroundings. Building and landscaping renovations in the early 2000s revived this charismatic hospital.

Mali

Modibo Keïta Sports Pavilion, Bamako, by E V Rybitsky and L N Afanasyev

The Modibo Keïta Sports Pavilion was originally built to house several entities. One was the sports arena, which was renovated in 2011 in order to host the Afro Basket championship that same year. The fully equipped pavilion can seat up to 1,100 spectators.

Its exterior envelope is made of claustra walls, for natural light and ventilation. The main facade is covered by a typical Soviet mosaic of painted tiles, which illustrates the pavilion's range of activities – be they athletic, cultural, or artistic. This artwork belongs to the best examples of the Socialist heritage in Western Africa.

The Gambia

Arch 22, Banjul, by Pierre Goudiaby Atepa

Arch 22 was designed to mark the 22 July 1994 takeover by the Gambian Armed Forces and completed in 1996. The building is set on eight columns and has three levels. The upper floors can be accessed via elevators and spiral staircases.

Level one is at an intermediate height, inside the columns. The gallery on the second level and the balcony at the top provide the visitor with an impressive panorama of the city, thus giving the spectator a good sense of Banjul as an island city, with the view extending down to the sea port of Banjul, and the mangrove forests of Tanbi Wetland Complex.

At the foot of the arch is a gilded statue of a soldier holding an infant – supposedly representing the rescue of the nation by the military, although critics have argued that the soldier looks more like a kidnapper than a rescuer.

Senegal

International Fair, Dakar, by Fernand Bonamy

Located close to the airport, the International Fair of Dakar complex is a conference and exhibition centre made up of four main areas: the Senegal pavilion, which is in fact the entrance hall; seven regional exhibition pavilions; exhibition halls surrounding the main pavilion; and a conference centre with a conference room and offices.

The architecture is based on the concept of asymmetrical parallelism established by president Senghor, and composed of simple 10 × 10 metre-square-based modular elements of reinforced concrete, and was inspired by the building systems of nomadic tents. The contrast between the rough texture of the façades, suggesting a fabric pattern, and the rigid, controlled geometry of the rest of the complex, as well as the scale of the pavilions, gives it a distinctive atmosphere.

The graphism and design elements, such as the shape, and the decorative patterns of the pavilions, were inspired by African traditions and suggest a nomadic desert settlement.

Niger

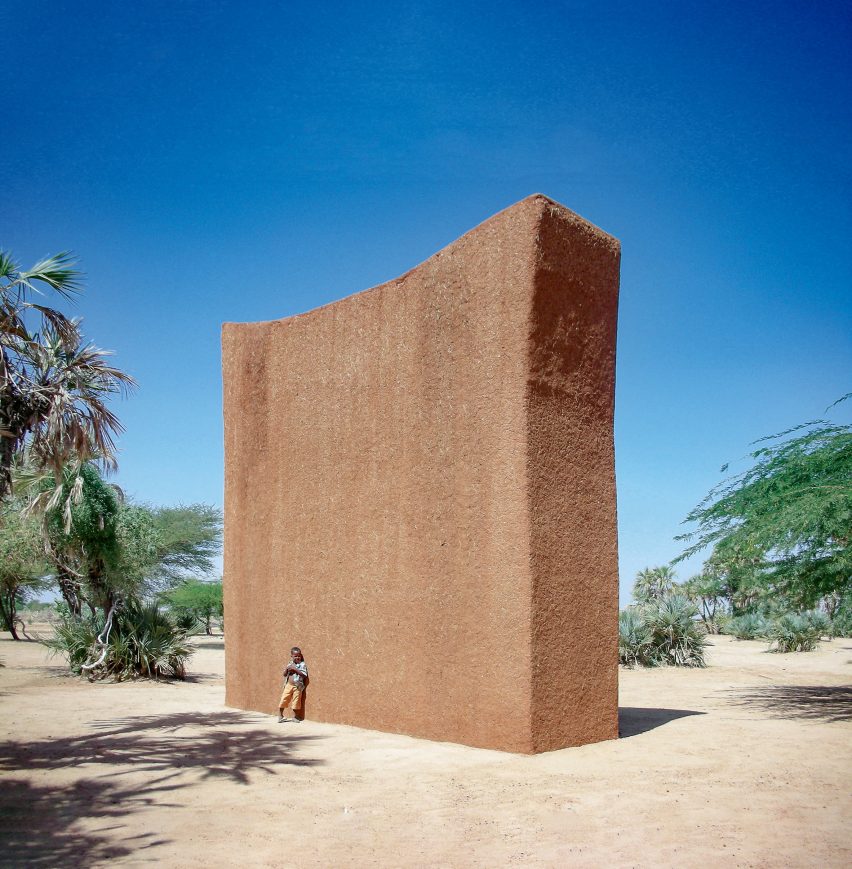

House to Watch the Night Skies, Aladab, by Not Vital

In 1999 the Swiss artist Not Vital went to the desert-city of Agadez in Niger to start building a series of architectural sculptures. In 2003 he went on to build a school, followed by House to Watch the Sunset, House to Watch the Night Skies (above), House Against Heat and Sandstorms and a Mosque.

All of these have varying degrees of functionality and exist somewhere in the realm between architecture and sculpture. The "function" of these works, as well as their appearance, especially House to Watch the Night, recalls the astrological gardens in India, reiterating Vital's interest in the cosmos.

The builders were very quick to finish their work and more so since there was no need for planning permission; this no-rules attitude allows Not Vital to revisit the immediacy and natural instinct of the habitats he made as a child in the forests. The beauty of the desert landscape is phenomenal and an inspiring backdrop for any artist or architect.