Barbican celebrates Matrix feminist design group in How We Live Now exhibition

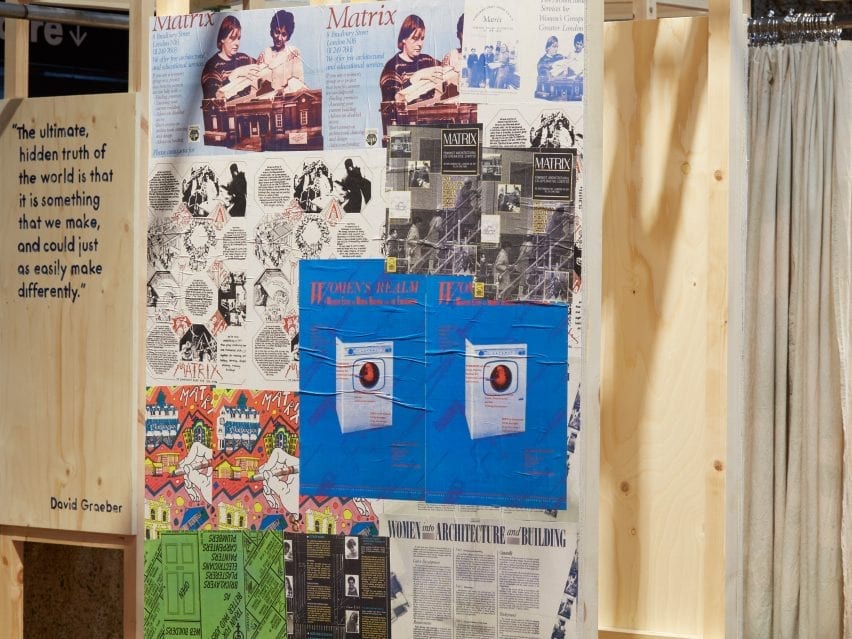

The pioneering work of 1980s group the Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative is the subject of How We Live Now, an exhibition at The Barbican that looks at the biases in architecture and the built environment.

Active in London from 1981 to 1994, Matrix were a non-hierarchical collective of female architects, designers, builders and activists who empowered marginalised communities to participate in the creation of spaces.

Their work saw them collaborate with Black and Asian women's organisations, childcare providers, and lesbian and gay housing co-operatives to build several projects in the UK, while also publishing manuals and running educational outreach.

Renewed recognition of Matrix's work came last year, when Part W chose the group as its 1985 winner in The Alternative List, which addressed the male dominance of the RIBA awards year by year.

In the months after, Matrix founding member Jos Boys, an academic at The Bartlett architecture school, received seed funding to build the Matrix Open feminist architecture archive, and Barbican assistant curator and Dezeen contributor Jon Astbury set out to create an exhibition based on the group's work.

The two ended up co-curating How We Live Now, which is subtitled "Reimagining Spaces with Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative". The free exhibition will run in The Barbican's ground-level foyer until 23 December 2021.

Astbury and Boys aim to both introduce new audiences to the concept that the built environment can be gendered, not neutral, and to allow more seasoned viewers to understand Matrix within the broader context of activism then and now.

Boys said that many of the group's members were driven to start a feminist practice after experiencing discrimination at architecture school or in the workplace.

"We were part of the New Architecture Movement, which was a radical movement kind of unionising architects, and yet even within that space, it was assumed that women should make the tea," Boys told Dezeen.

"For some of the women, their experience in architecture school had been pretty miserable. There were still very few women studying architecture, and they tended not to be taken very seriously. We all had comments that were like, 'at least you'll be able to design kitchens' or 'you'll go off and get married, so we're wasting our time educating you'."

The work they made did not share a common aesthetic; rather, it was about developing inclusive, participatory processes that would properly meet the needs of a building's users.

How We Live Now attempts to convey this focus on process and conversation. So for its display on Matrix's best known work, the Jagonari Women's Educational Resource Centre, a hub for South Asian women in London's Whitechapel, the documents displayed include a photograph of the group's "brick picnic".

On this outing, the Jagonari women walked the area discussing brick colours and textures, and were also prompted to bring photos of buildings they liked.

The building ended up being made with metal latticework windows and an ornate mosaic door — two features that were meant to remind the women of home, without arousing the racial harassment they feared from outsiders.

The exhibition also displays demountable scale models, another tool Matrix used to bring users into the conversation by making ideas visual and interactive.

Most of these objects haven't survived the intervening decades. Astbury was keen to highlight and celebrate these "gaps in the archive" rather than papering over them.

For that reason, there is a colourful newly commissioned demountable model of one of Matrix's projects, the Dalston Children's Centre, created by the contemporary feminist design collective Edit.

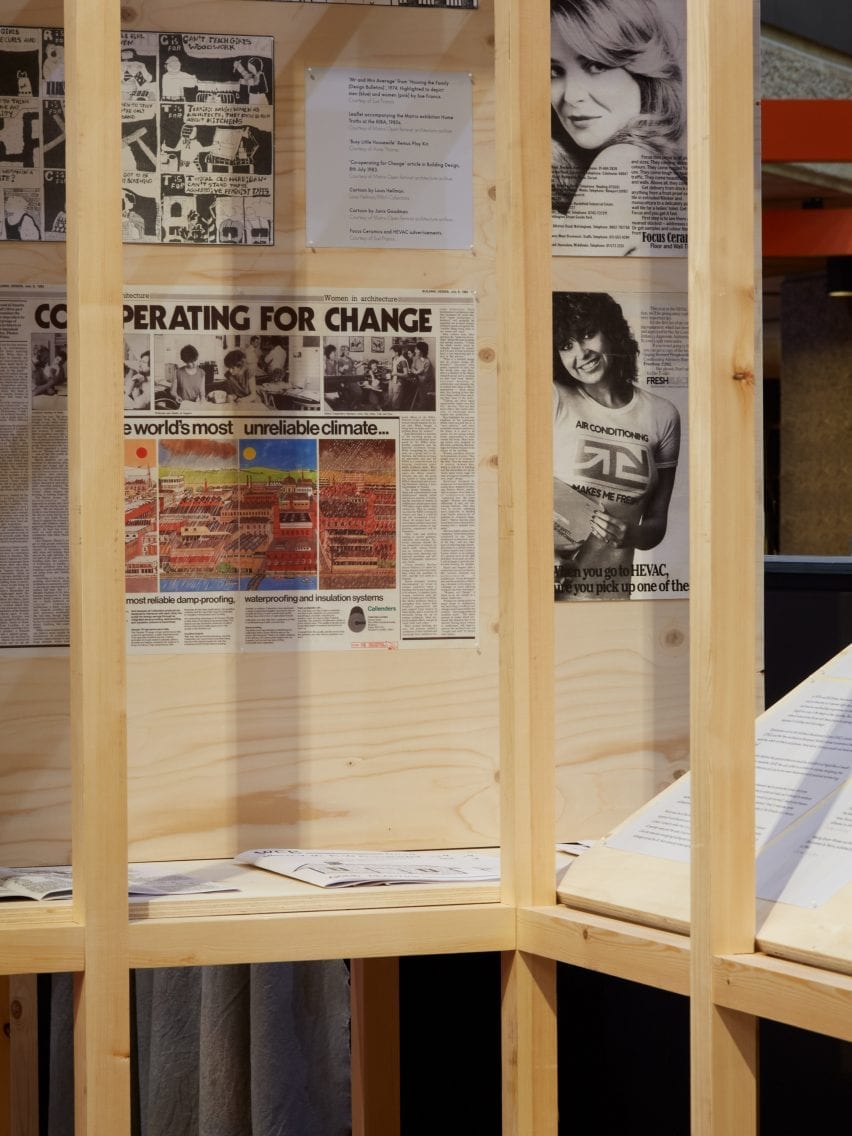

Edit also did the exhibition design, which is based on a wooden structure created by set builder Elouise Farley, the founder of education project Lady Wood.

Both Astubry and Boys wanted the exhibition to feel like an ongoing conversation rather than a relic of the past.

"We wanted to present the exhibition in a way that makes the ideas in it feel accessible and kind of active and ongoing rather than looking into a time that doesn't exist anymore," Astbury told Dezeen.

"Because yes, a lot has changed and the context has changed, but the ideas in the work and the kind of messages we wanted to pick up on are still incredibly relevant."

The final section of the exhibition features contemporary projects that pick up on some of the ideas in Matrix's work.

There is also a zine-like experimental exhibition catalogue, Revealing Objects, which brings together responses such as a map of women-designed London buildings produced by Part W, writing by the group Decosm (Decolonise Space Making) and an activity sheet by disability activists DisOrdinary Architecture for experiencing spaces with senses other the visual.

Boys is keen to both celebrate Matrix and recognise its limitations, at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement has expanded people's understanding of what a truly inclusive society should look like.

"Part of what Black Lives Matter did is really making white people understand that we are part of the problem," said Boys. "Second-wave feminism suffered from being centred on middle-class white women's problem of being the housewife, the Betty Friedan thing of the problem that has no name."

"So in terms of getting to grips with how space matters in terms of race, gender, class, disability, there were some things that Matrix and all the different women in it individually did that was really important, but I think there's lots of things that weren't done so well."

Astbury describes the most important legacy of Matrix as the idea that design is not neutral or passive.

"That combined with an emphasis on looking at the process of design rather than the end product," he said.

"And that the methods Matrix used in order to make the process of building and design more transparent and to reveal that lack of neutrality are incredibly straightforward. It's kind of depressing that we don't do it more, because it is so simple."

Photography is by Thomas Adank.