Ten materials that store carbon and help reduce greenhouse gas emissions

As our carbon revolution series continued this week, here are ten materials that store carbon including bioplastic cladding and mycelium insulation.

Sequestering carbon that has been removed from the atmosphere in buildings and products is a key way of tackling climate change.

This can be done by taking plant matter such as wood, cork, hemp and algae that has captured atmospheric carbon via photosynthesis and using it directly. Alternatively, it can be turned into other materials that store carbon more permanently.

"What if everything we're surrounded with was removing emissions instead of releasing them?" said Neema Shams of Made of Air, which makes carbon-negative bioplastic from forest and agricultural waste.

The material is carbon-negative because it contains more carbon than was emitted during the material's manufacture and use.

"Climate change is a material problem"

"Climate change is really a material problem in that there's too much carbon in the atmosphere. So how come we can't turn that into our biggest resource?" Shams told Dezeen in the interview conducted as part of the carbon revolution series.

Other products utilise carbon captured from factory chimneys and other industrial processes that emit greenhouse gases.

However, such products cannot be considered carbon negative, since they do not result in a net reduction in atmospheric carbon.

Dezeen's carbon revolution series explores how this miracle material could be removed from the atmosphere and put to use on earth.

Here are ten examples of carbon-storing materials from our archive.

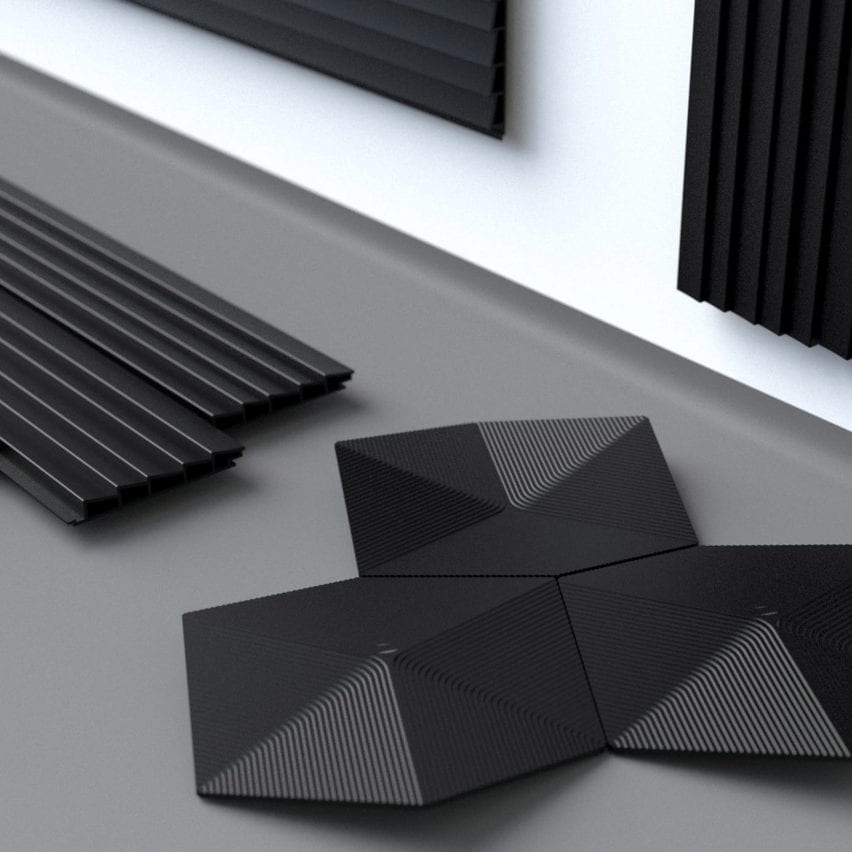

Bioplastic

German brand Made of Air has developed a carbon-negative bioplastic that can be used in cars, interiors and cladding.

The material contains biochar, a carbon-rich substance made by burning biomass without oxygen, which prevents the carbon from escaping as CO2.

"With biochar, if you just left it on the ground and came back a thousand years later, it would look exactly the same," Shams said. "Only if you were to burn it would that carbon be re-released."

The bioplastic was recently used to clad a car dealership in Munich with the installation storing 14 tonnes of carbon, according to Made of Air.

Find out more about Made of Air ›

Mycelium insulation

Start-ups including London-based Biohm are using mycelium to create building insulation that is naturally fire-retardant and removes "at least 16 tonnes of carbon per month" from the atmosphere as it grows.

Mycelium, a biomaterial that forms the root system of fungi, feeds on agricultural waste and in the process sequesters the carbon that was stored in this biomass.

Sustainability expert David Cheshire described mycelium as "part of the solution" to making buildings carbon-negative.

"It's naturally fire retardant," he told Dezeen. "It's actually got better insulation properties than most standard insulation and it's actually sequestering carbon."

Mycelium is fast-growing and cheap to produce in custom-made bioreactors. It can be grown in moulds to create usable products such as packaging and lamps.

It can also be turned into new materials including leather-like products such as Mylo. These in turn can be used to produce handbags and clothes.

Find out more about mycelium insulation ›

Carpet tiles

American carpet-tile manufacturer Interface is aiming to make its entire product range carbon negative by 2040, starting with the Embodied Beauty and Flash Line carpets that were released this year.

They are constructed almost exclusively from recycled plastic and various biomaterials, which the brand says store more embodied carbon than is emitted by the products in their production.

Interface describes the tiles as carbon-negative "from cradle to gate", meaning their lifecycle after they leave the factory is not taken into account.

"It's not carbon-negative for its full lifecycle because elements of transport and end-of-life use we can influence but we can't control at this stage," Interface sustainability leader Jon Khoo told Dezeen.

"So we wanted to focus on going carbon negative with what we can control."

Find out more about Interface tiles ›

Wood

A fully-grown tree can remove 22 kilograms of CO2 from the atmosphere over the course of a year, meaning that the material is carbon negative as long as it is responsibly sourced and that the felled tree is compensated by new planting.

Any carbon stored in the wood needs to be weighed against the emissions generated during transport and processing and replacement trees need to be left growing long enough so they themselves can be harvested and turned into carbon-storing materials.

However, one problem with wood is the tremendous amount of waste produced by the timber industry. Only part of each tree is used and processing timber generates significant amounts of offcuts and sawdust. In addition, only around 10 per cent of timber is recycled.

"Just think about carving wood," said sustainable-design guru Willian McDonough in an interview with Dezeen as part of carbon revolution. "It's a negative process, right? We're cutting away stuff all the time."

3D-printed wood

Additive manufacturing company Forust has developed a way of turning sawdust and lignin discarded by the timber and paper industries into a 3D printing filament.

By making products from waste, the company hopes to stop additional trees from being cut down as well as preventing the waste wood from decaying or being incinerated, which would re-release the carbon is stored.

"It could save a lot of trees," said McDonough. "It's kind of fun and it's quite beautiful."

Olivine sand

Olivine, which is one of the most common minerals on earth, is capable of absorbing its own mass in CO2 when crushed and scattered on the ground.

This means it lends itself to being a fertiliser and a replacement for sand or gravel in landscaping, while the carbonated version (above) can be used as an additive in the production of cement, paper or 3D-printing filaments.

"It absorbs CO2 very easily," said Teresa van Dongen, who has included the mineral in an online library of carbon-capturing materials.

"One tonne of olivine sand can take in up to one tonne of CO2, depending on the conditions. You just have to spread it out and nature will do its job."

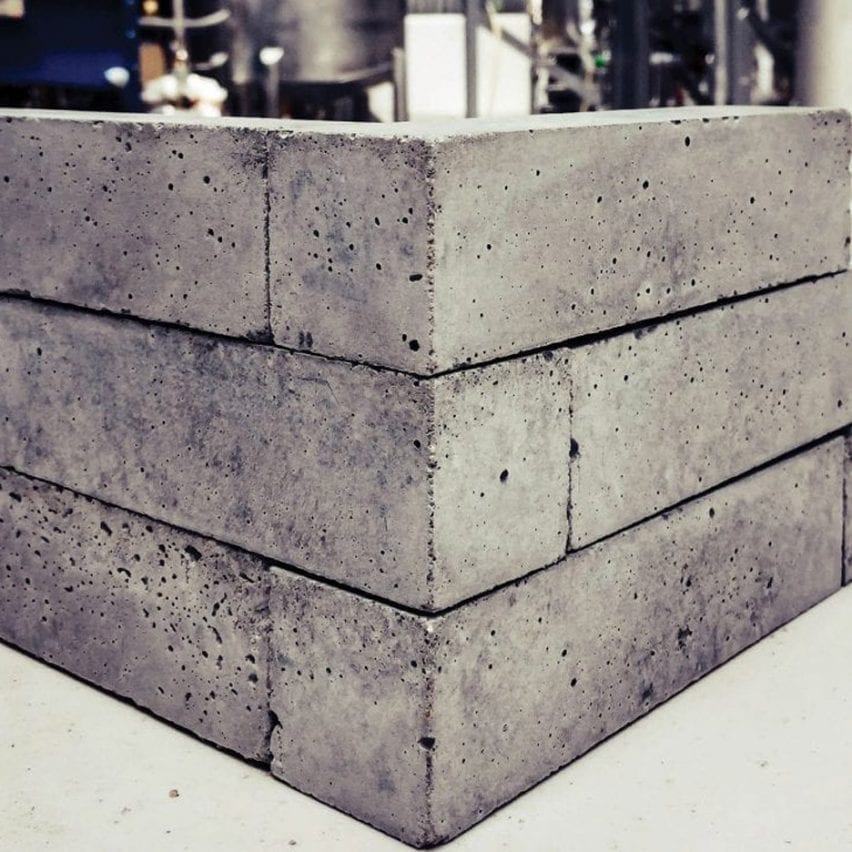

Concrete

Montreal company Carbicrete has developed a type of concrete that captures carbon in its production while substituting emissions-intensive cement, which is responsible for eight per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions, with waste slag from the steel industry.

Currently, the process relies on captured industrial emissions, meaning that it reduces the amount of new emissions being pumped into the atmosphere but does not reduce atmospheric CO2. However, once the company draws its CO2 from the atmosphere via direct air capture (DAC), this would make the final material carbon-negative.

"It's negative emissions," Carbicrete CEO Chris Stern told Dezeen. "We're taking CO2 out of the system every time we make a block."

Find out more about Carbicrete ›

Bricks

Australian company Mineral Carbonation International injects CO2 into industrial waste such as mine tailings, turning it from a gas into a solid that can then be used to create cement bricks and other building materials.

The process replicates the same mineral carbonation process that takes place in nature as carbon dioxide dissolves in rainwater and reacts with rocks to form new carbonate minerals.

"We're trying to embed emissions into as much of our everyday life as possible," said MCi chief operating office Sophia Hamblin Wang. "We turn waste into new products. And we aim to do it in a way that makes money."

Find out more about Mineral Carbonation International ›

Food

Solar Foods is one of a growing cohort of companies using emissions captured from industrial plants to create foods and drinks. The Finnish company uses microbes to turn carbon dioxide into a meat substitute called Solein.

The CO2 is injected into a fermentation tank together with hydrogen and different nutrients, all of which the microbes consume and turn into protein that is then harvested and dried, resulting in a powder with a similar composition to dried soy.

The carbon dioxide currently comes from industry but could one come from captured atmospheric carbon.

If scaled up, the technology could potentially provide humanity with its protein needs while using a fraction of the land and resources used by traditional agriculture, thereby freeing up more land for afforestation, solar power and other means of tackling climate change.

Producing Solein is entirely free from agriculture," said Solar Foods. "It doesn't require arable land or irrigation and isn't limited by climate conditions."

Find out more about Solar Foods ›

Vodka

Brooklyn-based Air Co uses CO2 to make vodka. The brand breaks down carbon dioxide with water and a proprietary catalyst in a reactor to create ethanol, which is then used to distil vodka.

"We invented a way to capture excess carbon from the air and turn it into ultra-refined, covetable products," Air Co said, although the claim is misleading since the CO2 comes from factory emissions, meaning it reduces rather than reverses greenhouse-gas emissions.

In addition, food and drink only offer short-term storage of carbon, since the product is soon consumed and the carbon returned to the atmosphere via the natural carbon cycle.

Find out more about Air Co vodka ›

Carbon revolution

This article is part of Dezeen's carbon revolution series, which explores how this miracle material could be removed from the atmosphere and put to use on earth. Read all the content at: www.dezeen.com/carbon.

The sky photograph used in the carbon revolution graphic is by Taylor van Riper via Unsplash.