Sandi toilet uses conveyor belt rather than water to dispose of waste

Solid waste is "flushed" away with a conveyer belt in the Sandi toilet, invented by recent Brunel University graduate Archie Read for the hundreds of millions of people who are currently living without safe sanitation.

Read designed his waterless, off-grid toilet primarily for rural sub-Saharan Africa, where this problem is particularly acute. But globally, more than 1.7 billion people did not have access to basic sanitation services such as private toilets or latrines in 2020.

Sandi is intended to function without being connected to a sewage system while keeping waste separated and free of contaminating chemicals, so that it can be safely disposed of or reused as fertiliser.

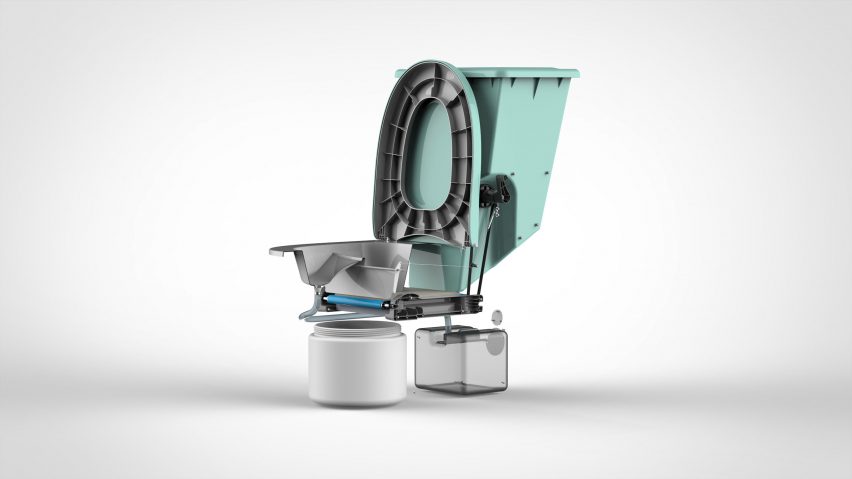

It features a Western-style toilet seat above a special toilet bowl that diverts the urine while solid waste is deposited onto a small conveyor belt.

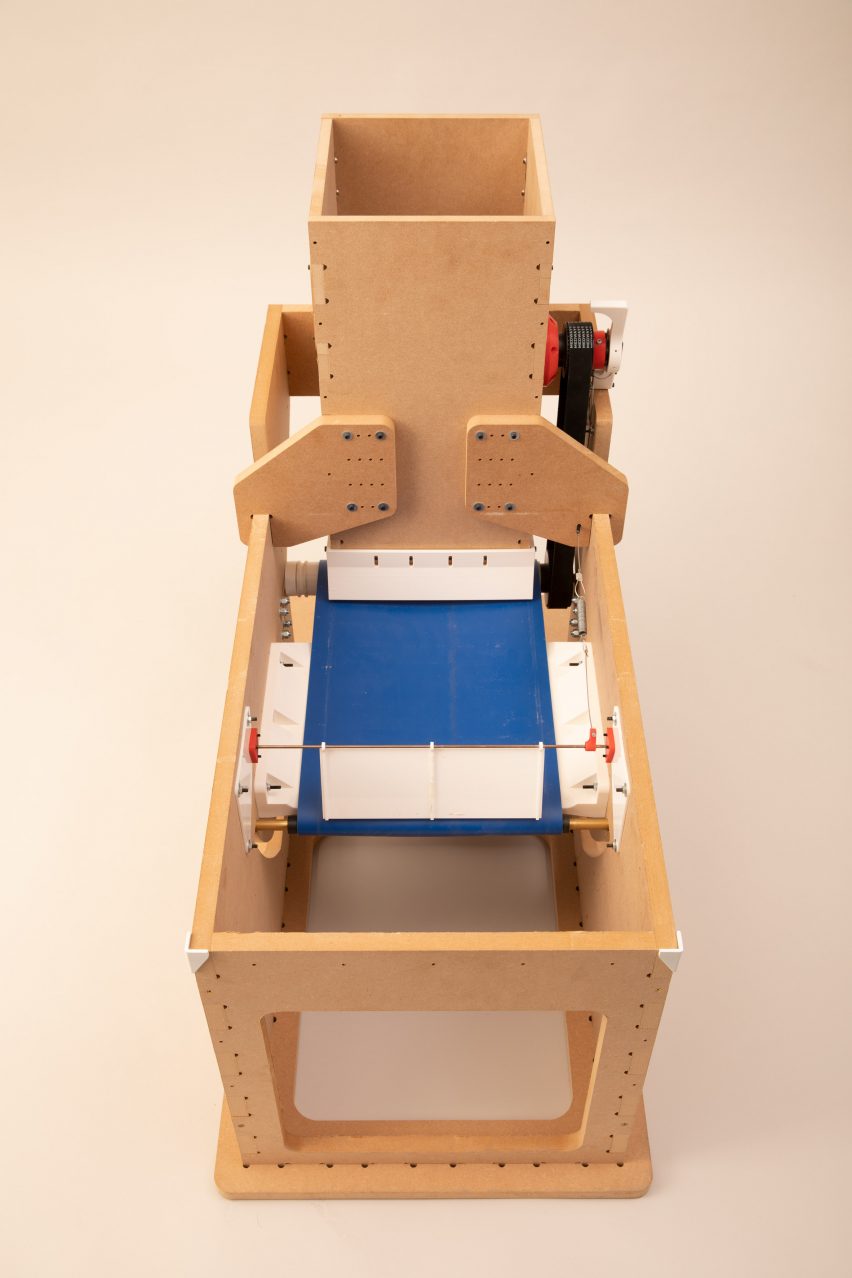

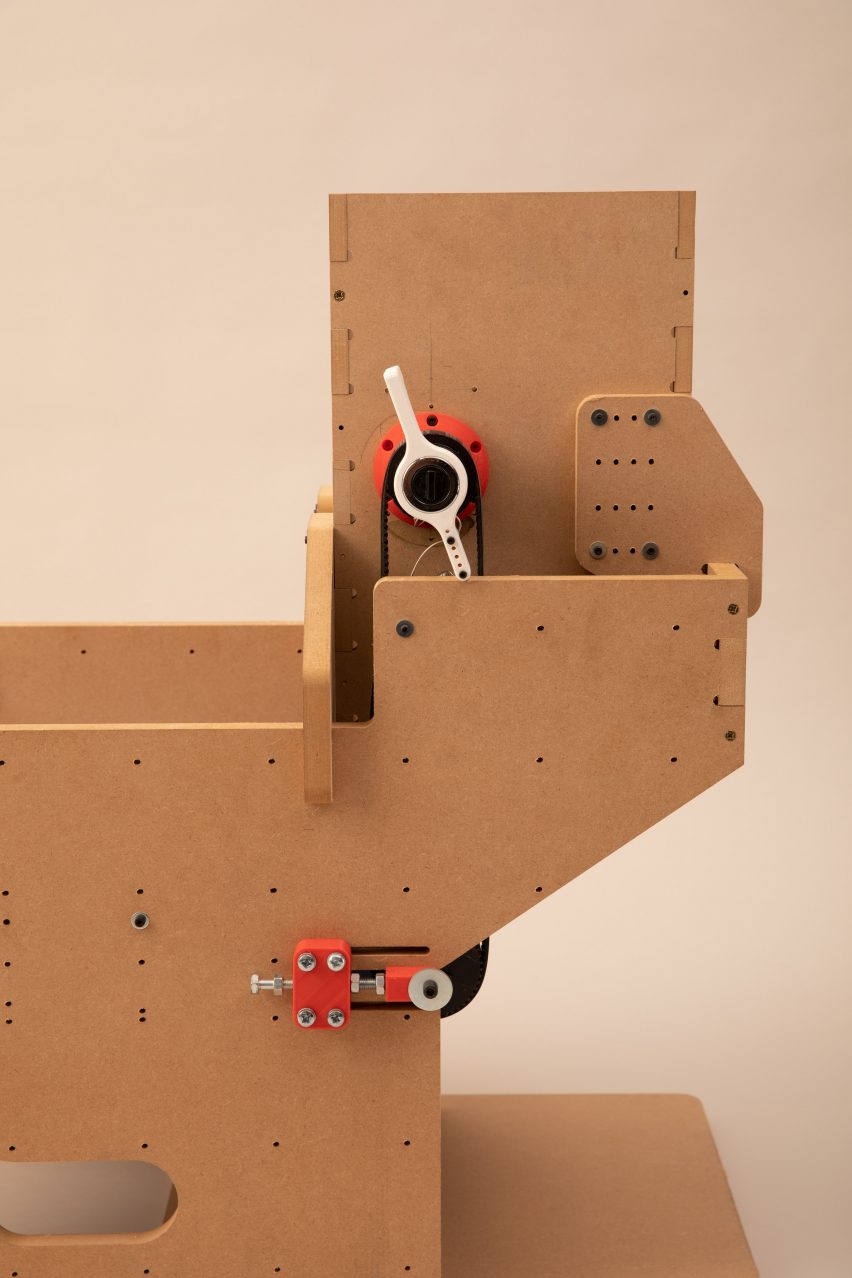

The toilet is "flushed" via a manual lever that moves the belt forward and drops the waste into a bin, sealed with a sprung hatch door to keep its contents safely out of reach of humans and household pests.

Since it requires neither plumbing nor electricity, Sandi acts as a "drop and go" solution that only needs to be pinned to the floor, Read says.

The design gets its name from the use of sand as a protective coating to keep the conveyer belt clean.

To use the Sandi toilet, a person would need to fill the hopper at the rear with sand or a similar locally sourced material. Anything dry and powdered or desiccated such as sawdust or dirt is suitable to stop faeces from sticking to the belt.

A crank of the flush lever causes fresh sand to be loaded onto the conveyer belt, at the same time as moving the belt forward. A brush on the underside of the belt cleans off any residue remaining after the waste's disposal.

The flush only needs to be pulled for solid waste, as the toilet bowl's design uses a physical divider to direct urine to a separate container at the front of the toilet.

"It is key to do this as urine is kept sterile and faeces is allowed to dry out, which helps prevent pathogen reproduction and decreases the composting time," Read told Dezeen.

The bins can store 20 litres of solid waste and 30 litres of liquid waste, which Read estimates would allow a household of seven to go around nine days without needing to empty the containers.

Ultimately, the waste disposal would likely be handled differently depending on location, he says.

In villages, a person may be employed to collect the used containers and replace them with clean ones, while more isolated individuals might handle the disposal themselves and repurpose the waste for fertiliser.

"The urine can be used straight away, as it is sterile if never in contact with faeces, so they can simply water it down and use it as fertiliser," said Read.

"The reason for reusing the waste streams as fertiliser rather than trying to recover biogas or chemicals is that it is cheap. And as the target market for Sandi is rural communities, fertilisers will be quite valuable to them."

Read developed a working prototype and a 3D-printed scale model of Sandi as part of his bachelor's degree in product design engineering at Brunel University.

He envisages a production version of the product would be made from cost-effective high-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastic but has put off further development until he has more industry experience.

Other student projects featured in Brunel's school show on Dezeen include a minimalist air quality monitor and a Reading Monster toy that allows children to independently learn the alphabet.