Will architects really lose their jobs to AI?

As part of our AItopia series exploring how AI will impact architecture and design, Dezeen examines whether the technology will end up taking architects' jobs.

In 2019, New York-based designer Sebastian Errazuriz caused a stir with his claim that 90 per cent of architects could lose their jobs to machines.

Four years on, following the emergence of several generative-AI models such as Midjourney and ChatGPT, Errazuriz is writing a book about AI's impact on society and told Dezeen his opinion has not changed.

"It's an enormous issue that we need to try and deal with," he said. "People always say, 'but isn't AI just another tool?' Right now it looks like a tool, but the tool is getting really good, really fast – and the purpose of this tool is to think for itself."

He claims that well-known architects who mocked his warnings in 2019 have recently conceded privately that he was right.

Architecture at high risk of automation

Investment bank Goldman Sachs made headlines in March with its prediction that AI could replace the equivalent of 300 million jobs globally across all industries. The researchers estimated that 37 per cent of architecture and engineering work tasks "could be automated by AI", placing it among the most-exposed industries.

And this month, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development echoed the warnings about job losses in skilled professions.

A survey conducted by design technology firm RevitGods found that 55 per cent of US architects are "moderately concerned" about being replaced by AI in the future, with a further 20 per cent "very concerned".

But not everyone shares Errazuriz's pessimism. Among them is Phillip Bernstein, associate dean and professor adjunct at the Yale School of Architecture who previously held senior roles at software firm Autodesk and Pelli Clarke Pelli Architects and has authored a book on architecture and AI.

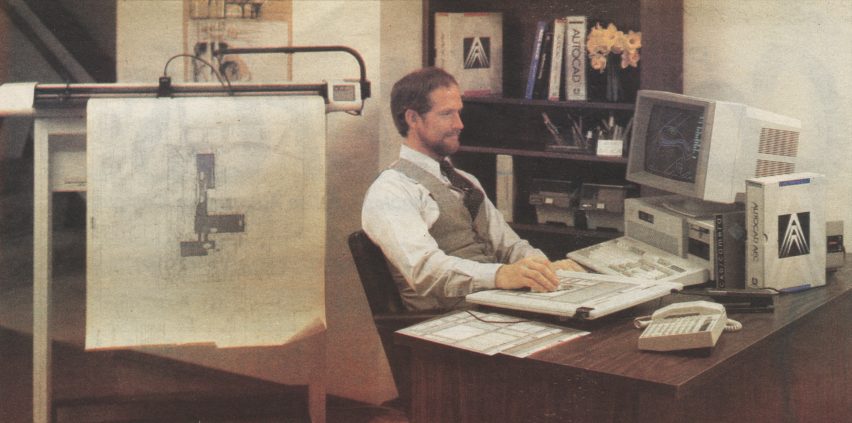

"I have been around long enough to see multiple waves of technological change in the industry and this argument happens every single time," Bernstein told Dezeen.

"It happened during CAD [computer-aided design], it happened during BIM [building information modelling], and now it's happening with AI," he added. "We somehow always seem to survive these things."

Bernstein argues that even the best AIs are still nowhere near the competence of a qualified architect.

"I happen to think that what we do as architects is pretty complicated," he said. "At it's best, it's about managing a complex, multi-variable problem and making a series of ambiguous judgements that require trade-offs, and I don't believe we will get to a model that can do even 10 per cent of that in the foreseeable future."

"If we're not even at the point where a car can drive itself, I think we're a long way from the point where an algorithm can be a professional architect," he continued.

"Our current traditional methodology will radically change"

The possible emergence of artificial general intelligence in the future – a hotly debated topic – would likely upend all intellectual industries and much of our current society.

For now, most people's idea of AI architecture is likely the dreamlike, eerily real-looking visualisations created with text-to-image models such as Midjourney. However, AI tools created specifically for use in architecture and design are beginning to enter the market.

Combined, the most advanced of these can generate massing images, floor plans, cost analyses, material specifications and technical drawings – though none can yet do it all.

In a recent interview with Dezeen, the co-founder and CEO of one of the leading systems, LookX, dismissed the idea that it could replace architects.

Instead, Wanyu He argued, AI "will liberate us from repetition and allow us to concentrate on things with added value to society".

In particular, He claims it will dramatically speed up the feasibility-testing process, freeing up time to spend on the more creatively rewarding aspects of architecture.

Few have spent more time experimenting with AI-architecture tools than Harvard Graduate School of Design research associate and ArchiTAG co-founder George Guida. He agrees that the technology will not replace architects anytime soon.

"Our current traditional methodology will radically change, but not be substituted," said Guida. "I do think that architects still will need to stay at the centre of being the driver within that process."

"So I think productivity will increase – let's say we'll have more time and space to design. I think that the role of the architect will simply have to evolve, but it won't be replaced," he continued.

"It will give smaller firms a stronger edge"

But even if AI is not capable of usurping the human architect outright, could architecture jobs still be lost as the technology is adopted?

"I do think there are large swathes of the work that are potentially automatable by AI," said Bernstein. "So the question is what happens to that additional capacity. Do we use it to do our jobs better, or do we eliminate some of those jobs?"

While both believe that AI could eventually be used by developers to design the simplest, most generic projects in-house, Bernstein and Guida are optimistic that the technology presents an opportunity for architecture studios to command higher fees.

"If I can say to a client that I'm using this tech to do a better job, then maybe I can charge more for my time," said Bernstein.

That could give smaller studios that are quick to adopt AI a chance to compete with bigger firms, argues Guida.

"Increasing productivity gives a great opportunity for emerging practices to bring a competitive edge," he said. "So in the short term it won't remove jobs – if anything, it will give smaller firms a stronger edge."

But Errazuriz remains unconvinced. He thinks the major impact will be at bigger firms, where, he points out, only a small handful of employed architects spend a significant portion of their time on creative work.

He argues the idea that AI will enable all these architects to remain in their jobs and simply spend more time exploring their imaginations is "wishful thinking".

"What will most probably happen is that you just start reducing the size of those architecture studios," he said. "Depending on how really good this software gets, in the worst-case scenario they would continue to decrease enormously over a 10-year period."

His comments appear to chime with remarks made earlier this year by Morphosis founder Thom Mayne that AI will lead to a decrease in the number of architects in individual studios to a "more intimate" level.

Wider factors at play

An alternative outcome is that the productivity gains afforded by AI could lead to studios – and therefore their employees – taking on more projects at once.

Architecture critic Kate Wagner has argued this was the main upshot of CAD, lengthening working hours despite similar hopes in the technology's early days that it could free up time for creativity.

Bernstein hopes that the adoption of AI in architecture won't see history repeat itself.

"It's true that CAD didn't enhance the value proposition of architecture, but it was happening alongside a period of buildings getting much more complex and the design and construction industry getting riskier," said Bernstein.

"So architects were drawing more defensively, and CAD made doing that easier. Now, as we are starting to leverage data about buildings to much greater effect, there is a potential value proposition there."

Saudi-based architect Reem Mosleh, who has made a name for herself as a leading voice on AI design, agrees that other factors will influence how the technology ends up impacting the architecture profession.

For instance, she believes it could reduce overtime in combination with a wider cultural shift away from working long hours.

"After Covid, people's priorities in life have changed drastically," she said. "So I really hope that with AI we could actually have this opportunity to live with better balance."

"You can't run away from it"

Regardless of their opinion on the threat that AI poses to jobs, everyone Dezeen spoke to agreed that architects should be proactively getting to grips with the technology.

"If I were a young practitioner I would be playing with this stuff so I understand it, and if I were a practice I would be giving practitioners time to try it out," said Bernstein.

"You can't run away from it, you need to run towards it," said Errazuriz. "Otherwise you'll be like those people that refuse to have a cell phone. You need to stay up-to-date, checking the latest things that come out and incorporating it into the flow or your team or your own work."

"For now, we're the ones giving the prompts," he added. "And so we need to sort of dig deep into our own creativity, into our storytelling, into why we're doing something."

Mosleh is hopeful that any disruption to architecture jobs will be outweighed by new opportunities opened up by AI.

"Architects who decide not to go beyond their normal practice will definitely be at risk," she said. "If you don't evolve you get replaced, it's nature."

"But at the same time I'm sure that those who are seizing the moment, and taking the opportunity will actually have better jobs and more opportunities."

The main image was created using Dall-E 2.

AItopia

This article is part of Dezeen's AItopia series, which explores the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on design, architecture and humanity, both now and in the future.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen's interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.