Apollodorus Architecture proposes classical alternative to Bath Rugby stadium

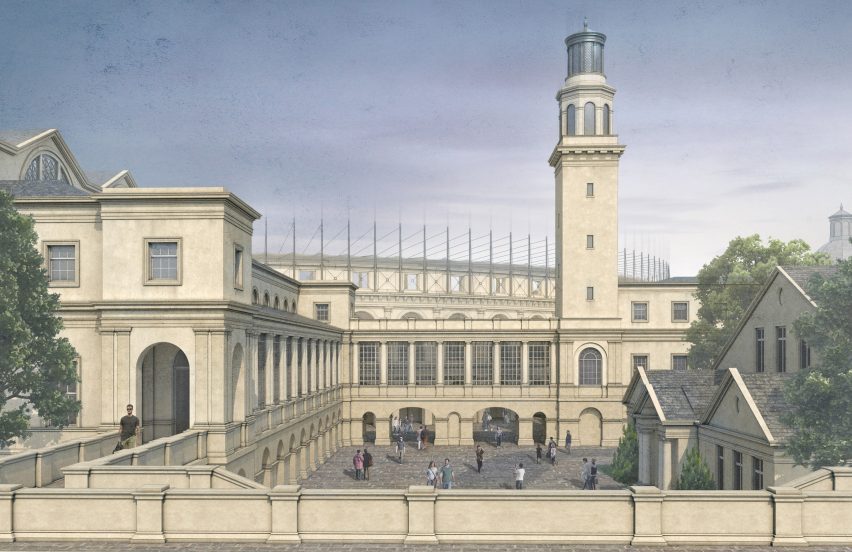

British studio Apollodorus Architecture has designed a Colosseum-like stadium in Bath, UK, as a response to a proposed redevelopment put forward by Bath Rugby.

Apollodorus Architecture proposed the redesign of the Recreation ground site in the centre of Bath, which is currently being redeveloped.

A final development brief was recently submitted for the project that has a rectangular shape and long, straight roofs, which Apollodorus Architecture argues are "at odds with Bath's animated roofscape".

Apollodorus Architecture's alternative scheme, which was designed by the studio's director Mark Wilson Jones with Jakub Ryng, would feature an oval shape that references Roman amphitheaters.

The studio believes this would merge more organically with the context of the surrounding city than the proposed stadium.

"Architecturally, there is actually very little to speak of," Wilson Jones said of the official Stadium for Bath proposal. "The new design put forward by Bath Rugby is clearly an expedient budget solution."

"In some respects, this actually makes it more successful and more likely to secure planning than the club's previous proposals for the site," he told Dezeen.

"But putting the architecture aside, our main issue with the current scheme is that by not engaging with the site in its entirety – that is, including the leisure centre – it would torpedo any possibility of a happier long-term future for the area."

His studio, whose work is "rooted in research, scholarship and the experience of historic architecture", has instead visualised an oval design that would have a capacity of around 18,000 – the same as the official proposal.

It believes this better adheres to Bath's historical origins while being more fitting for the site itself, which has an existing leisure centre from the 1970s that is set to be refurbished and improved as part of the new plan.

"The key to unlocking the site's potential is planning the stadium in conjunction with the leisure centre," Wilson Jones said. "Once we realised this, we settled on using an oval and not a rectangle for the stadium."

This shape would also have the benefit of not creating any hard corners, he added.

"The Romans invented the ellipse or oval for spectacles, so the choice seems apt given the city's Romano-British origins," Wilson Jones said.

"An oval has less bulk than a rectangle serving the same capacity and no hard corners. The curving structure of the proposed amphitheatre can merge organically with its context, as do Bath's Georgian crescents, softening the impact on critical views to and from the enclosing hills."

As well as the stadium itself, Apollodorus Architecture's counter-proposal – which it sees as both a theoretical exercise and a "provocation" – features a new leisure centre divided into two blocks.

It also envisions a new terraced riverfront and a collection of bars and restaurants, which would be located in the arena and the leisure centre. The new stadium and the surrounding buildings would be made from stone.

"In the ideal world, we would minimise the use of concrete and rely on locally-sourced Bath stone," Wilson Jones said.

"Contrary to what some people think, there is actually still enough of it in the ground for decades if not centuries."

Wilson Jones, who is an architect and historian teaching 18th to 20th-century architectural history and theory, said that Apollodorus Architecture is not dogmatic about the classical language and "can appreciate good contemporary buildings in the modernist idiom".

He argues, however, that Bath is a "slightly special case".

"The city as we know it was built in a relatively short period of time, out of a uniform building material, following a particular strand of classicism," Wilson Jones.

"It has survived more or less intact despite various post-war attempts to bring it up-to-date with the so-called 'Zeitgeist' – a very illusory and largely propagandistic concept," he added.

"It is therefore in the spirit of continuity and respect for Bath's enduring built heritage that we have chosen to work with the classical language – while being quite aware that it would stir up debate!"

The public response to the proposal has been "overwhelmingly positive," Wilson Jones said. However, he conceded a "very small number of architects" had reacted less favourably.

"What will be interesting is to see how younger architectural professionals, and students, will react, for nowadays they tend to be much more open-minded than those over 35 or so – those who were taught, persuaded, and sometimes inculcated with the seductive mantras of the hard-line modernists who after world war two ran anyone sensitive to the lessons of history out of town," Wilson Jones said.

"In a world that is rightfully becoming more broad-minded and tolerant of differences, the modernists' puritanism when it comes to architecture often feels hypocritical and bigoted," he added.

"However, to help those for whom the classical detailing may be an intellectual obstacle, our website also features a 'stripped-down' version of the scheme."

Also in the UK, Dezeen recently featured a neoclassical country house designed by Robert Adam, which will be "UK's largest new home for over a hundred years".

In an opinion reflecting on the continued debate between modernist and historical architecture Barnabas Calder wrote that "both sides in the style wars are equally wrong". He argued that the squabble was an unhelpful distraction in the face of the climate emergency.

While architecture critic Robert Bevan argued that King Charles III's love for traditional architecture meant he is "entangled in the far-right's weaponisation of architecture."

The images are courtesy of Apollodorus Architecture.